The Art of Gaming: Yesterday and Today

by RadiumEyes, HSM team writer

In 2012, the Smithsonian Institute contained an exhibit on video games – with five sections dedicated to different periods of the medium’s history, The Art of Video Games demonstrated the artistic value of interactive works ranging from classic Atari games to modern fare. The sheer breadth of its scope (ranging from early releases such as Space Invaders to recent works such as Uncharted 2 and Brutal) stands as a testament to how far we, as a society, came in accepting digital media as a viable form of artistic and social expression; a major museum is willing to display video games within its walls, a validation of the decades of hard work found in the industry. Burbie’s recent article on the landscape of Final Fantasy XIV reminded me of this – we live in a time where we can discuss the aesthetic merits of popular games, as we see games with a more cinematic tone and great artistic diversity.

I tip my hat to Burbie for introducing this topic, as this happens to be quite a wonderful one for discussion; when one looks at the worlds you play in while getting from point A to point B, things feel alive and energized, as the landscape provides the player with a digital playground to interact with. Writing an article about the history of the video game (especially when it comes to art) may be a daunting task, but it would be a labor of love – with the Smithsonian’s aforementioned 2012 exhibit, art in digital form now has a far greater voice than it once had. Remember when the first consoles debuted? The Bally Astrocade, for example, looked like a miniature computer with (comparatively) little capacity, but the generation it was part of defined the “classic” video game style. Which brings me to my article here – with the eighth generation upon us, some retrospection would be great in presenting how the console market evolved since the 1970s. I hope, with this article, to show the depth of the video game as an art form, regardless of the era it came from.

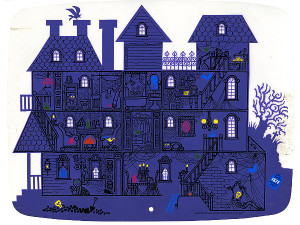

Let’s begin, shall we? The Magnavox Odyssey, released in 1972, has the distinction of being the first commercially-available home console; it came with overlays that were placed over the television screen, as well as other accessories such as dice and score sheets. One of these overlays featured a haunted house, used to play (appropriately) Haunted House; this particular game required two players, one to be the ghost, another a detective assigned to locate said ghost through a series of clues. The console itself only had the capacity to show blobs of light, which the player could control at leisure; in fact, one could move said lights independently of the game being played, resulting in a rather curious case where players didn’t have any restrictions of movement. James Rolfe demonstrated this when he played the Odyssey for one of his Angry Video Game Nerd segments – as he notes, the system came with numerous peripherals (including a roulette wheel), and the games never kept score or timed your progress. The tennis outing released for it allowed players to move the ball all over the place, making the game rather fun (and funny) in the process; by contrast, Pong controlled the ball, while the player maneuvered the paddles to intercept it.

Let’s begin, shall we? The Magnavox Odyssey, released in 1972, has the distinction of being the first commercially-available home console; it came with overlays that were placed over the television screen, as well as other accessories such as dice and score sheets. One of these overlays featured a haunted house, used to play (appropriately) Haunted House; this particular game required two players, one to be the ghost, another a detective assigned to locate said ghost through a series of clues. The console itself only had the capacity to show blobs of light, which the player could control at leisure; in fact, one could move said lights independently of the game being played, resulting in a rather curious case where players didn’t have any restrictions of movement. James Rolfe demonstrated this when he played the Odyssey for one of his Angry Video Game Nerd segments – as he notes, the system came with numerous peripherals (including a roulette wheel), and the games never kept score or timed your progress. The tennis outing released for it allowed players to move the ball all over the place, making the game rather fun (and funny) in the process; by contrast, Pong controlled the ball, while the player maneuvered the paddles to intercept it.

Speaking of Pong, this 1972 classic marked the emergence of the video game as a popular medium; fans of Saturday Night Live might remember segments in the earliest season where two characters chatted while playing the cabinet. Unlike the Odyssey, Pong actually kept score, and the entire game was self-contained; you didn’t need anything extra (such as dice or a scorecard) to play it. The simple, black-and-white screen offered no distractions or frills whatsoever – you had a paddle that moved vertically, and the only goal was to score 10 points, or thereabouts by moving the ball beyond your opponent’s side of the screen. The company who released Pong, Atari, became the dominant entity in the nascent video game industry; Atari’s success would not last, however, as attested by the infamous E.T. tie-in game, but that’s a story for another day. When looking at the first and second generations of consoles, one sees a slew of competitors and systems vying for attention, much like today – with the less complex hardware and chips, however, the earliest games did not have enough room for things like an overarching narrative, side missions or length. Many of the games featured sports or other such diversions; to give an example, Nintendo released its first version of Duck Hunt in 1976, a year before the debut of its first Color TV-Game console. This version used a projector that cast the game screen onto a wall; the single image of a flying duck was achieved through an electro-motor connected to a mirror over the lens of the projector, which contained the duck-shape plate and a light bulb.

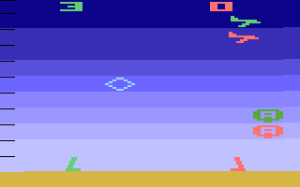

Such was the state of video gaming in its earliest years; when the second generation rolled around (with the release of the Odyssey), new innovations such as microprocessors and AI simulation paved the way for new explorations. Atari’s 2600 model pretty much symbolized this period; its nominal successors, the 5200 and 7800, didn’t get anywhere near as much attention as the original, and today, Atari’s legacy as a founding industry rests mainly on that console. For the first time, games supported color, even if they seem rudimentary today; look at Air-Sea Battle for the 2600, one of the console’s nine launch titles, for an example of how the use of basic colors and gradations allowed for distinctions between player and AI units. Air-Sea Battle features has a time limit (two minute, sixteen seconds), and the various game modes showed rather blocky textures; however, this made the game all the more endearing, as it expanded the video game’s visual library by presenting objects that looked vaguely like their real-life counterparts. One could make out airplanes and anti-aircraft guns here, and other games offered similar experiences – the 1977 game Blackjack showed actual card values (although it did not include suits), and the later Berzerk puts players in the control of a human character fighting robots. Due to the limitations of the console, games on the 2600 could only allow basic representations of objects and living beings; however, they struck a chord with audiences because of their simple charm and plain graphics. Those who grew up playing the 2600 may recognize Yars’ Revenge, one of the most famous releases for the console; the game consists of a wasp-like character (controlled by the player) as it brings down the shield of an enemy vessel and destroys its core. An accompanying comic book revealed the backstory, something that had not been done in the previous generation; now, players could see the evolution of the Yars and their struggle against the Qotiles.

With a brief glimpse into the dawn of the industry, let’s move ahead to the current generation, with a look back at some earlier consoles. Although barely over six months old, the Playstation 4 debuted at a time when the industry pushed towards HD and Blu-Ray; the old days of the AV cable may soon be over, with HDMI fast becoming a standard for consoles. With this move to high definition came a concomitant development in graphics; games like Flower and Journey show off the incredible detail one could accomplish with the current generation, and both illustrate the diversity of gameplay and how art style complement one’s experience. Journey, which debuted on the PlayStation 3, is practically a work of art unto itself – the image of the mysterious robed figure moving through the desert landscape speaks to the personal journey one finds in any video game. The sublime beauty of the landscape perfectly complements the silent narrative and the unknown quest the player engages in; nowhere does the game explicitly state your goal, making the journey itself the focus.

With a brief glimpse into the dawn of the industry, let’s move ahead to the current generation, with a look back at some earlier consoles. Although barely over six months old, the Playstation 4 debuted at a time when the industry pushed towards HD and Blu-Ray; the old days of the AV cable may soon be over, with HDMI fast becoming a standard for consoles. With this move to high definition came a concomitant development in graphics; games like Flower and Journey show off the incredible detail one could accomplish with the current generation, and both illustrate the diversity of gameplay and how art style complement one’s experience. Journey, which debuted on the PlayStation 3, is practically a work of art unto itself – the image of the mysterious robed figure moving through the desert landscape speaks to the personal journey one finds in any video game. The sublime beauty of the landscape perfectly complements the silent narrative and the unknown quest the player engages in; nowhere does the game explicitly state your goal, making the journey itself the focus.

Going towards fighting games now, Arc System Works really worked to make the BlazBlue series look great – the characters of Rachel Alucard, Ragna the Bloodedge and Amane (among many others) move quite fluidly, and the backgrounds from each entry all appear vivid and alive. Some of the first games in the genre, such as the original Street Fighter II and the Fatal Fury franchise, didn’t have quite as much action going on in the background, but they were no less artistic for that reason – in fact, these entries into the fighting game lexicon really cemented how the video game could be art. If one looks at the stages of Real Bout Fatal Fury, one can see the endless stretch of Sound Beach or the imposing interior of Geese Tower; an image of a boxing match poster from the first Fatal Fury pays homage to commercial art of the period, when Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Julio Cézar Chávez rose to prominence in the late 1980s. One the other end of the spectrum, abstract games such as Thomas was Alone looked back at the more pixelated days of gaming, and echoed some of the De Stilj movement – Piet Mondrian, in particular, became famous for his non-representational forms, which utilized geometric shapes (especially rectangles, squares and solid lines) to present an unadorned artform that didn’t rely on representations of humans, natural formations or any other “traditional” methods of artistically representing the world around us. Thomas was Alone extends this motif into the interactive world – basic human experiences such as love become the focus, as the characters are de-emphasized physically. Since the narrator fills us in with the narrative, we can concentrate on the characters as characters, without any obvious physical gender signifiers; they go through the same struggles as all of us, reminiscent of the classic Chuck Jones short The Dot and the Line.

Indie games today test the waters of both narrative structure and aesthetic design; take Limbo, for instance. The game takes place in a black-and-white world, where the player-character must navigate dangerous obstacles on his quest to locate his sister; the minimal story gives a sense of foreboding, and the artwork (reminiscent of film noir and, possibly, H. P. Lovecraft’s tales) look at the sinister side of an uninhabited world whose existence seems to defy the player’s comprehension. Sparse lighting from the sun really makes this game unsettling; you’re not sure where you are, and the environment becomes one major blur. Notice how the trees and the far background appear out of focus, as if a fog swept into the scene – is it a dream, a trance, a jungle where the spirits reside? The various creatures you encounter blend in with their surroundings, giving them a stealth advantage – since your character has little in terms of physical ability (he’s no superhero or warrior), he must use the environment to even the odds. By contrast, look at the brighter colors of Guacamelee! Influenced by Mexican culture, particularly the luchadore and early Mesoamerican art, the game incorporates the “land of the dead” theme, as Juan Aguacate must navigate the underworld to bring El President’s daughter back to the mortal realm. What makes Guacamelee! so astounding is its inclusion of Mesoamerican and Mexican culture – an actual Tule tree exists, in Santa Maria del Tule; this immense tree has a legend attached to it, from the Zapotec culture. The game also revels in video game culture, with references to the Metroid series, Legend of Zelda and even Internet memes; at the same time, however, the inclusion of historical figures such as Malinche raise the important issue of cultural appropriation. Malinche, for those who haven’t heard of her, worked as an interpreter for Cortés, and she became a symbol as both a founder of modern Mexico and a traitor (the latter derived from her important role in the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire).

Indie games today test the waters of both narrative structure and aesthetic design; take Limbo, for instance. The game takes place in a black-and-white world, where the player-character must navigate dangerous obstacles on his quest to locate his sister; the minimal story gives a sense of foreboding, and the artwork (reminiscent of film noir and, possibly, H. P. Lovecraft’s tales) look at the sinister side of an uninhabited world whose existence seems to defy the player’s comprehension. Sparse lighting from the sun really makes this game unsettling; you’re not sure where you are, and the environment becomes one major blur. Notice how the trees and the far background appear out of focus, as if a fog swept into the scene – is it a dream, a trance, a jungle where the spirits reside? The various creatures you encounter blend in with their surroundings, giving them a stealth advantage – since your character has little in terms of physical ability (he’s no superhero or warrior), he must use the environment to even the odds. By contrast, look at the brighter colors of Guacamelee! Influenced by Mexican culture, particularly the luchadore and early Mesoamerican art, the game incorporates the “land of the dead” theme, as Juan Aguacate must navigate the underworld to bring El President’s daughter back to the mortal realm. What makes Guacamelee! so astounding is its inclusion of Mesoamerican and Mexican culture – an actual Tule tree exists, in Santa Maria del Tule; this immense tree has a legend attached to it, from the Zapotec culture. The game also revels in video game culture, with references to the Metroid series, Legend of Zelda and even Internet memes; at the same time, however, the inclusion of historical figures such as Malinche raise the important issue of cultural appropriation. Malinche, for those who haven’t heard of her, worked as an interpreter for Cortés, and she became a symbol as both a founder of modern Mexico and a traitor (the latter derived from her important role in the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire).

To round off this article, a few more games should be examined for their artistic merit. Bioshock Infinite, the third installment of the Bioshock franchise, takes place in 1912; Irrational Games really did their homework when it came to a somewhat accurate portrayal of the difficult times experienced by minorities and workers during the early 20th century. As far as art goes, Infinite really pulls no punches when presenting the racist ideas found in the time period; the bloodied corpse of Chae Lim is a visceral, frightening image to behold, a reminder that people of Chinese descent did not receive any respect at the time, for various reasons. The racial and social tension of Columbia echoes the general history of the United States; Zachary Comstock wished to create a religious utopia in the clouds, away from the “Sodom Below” (which he perceives to be the epitome of wickedness and sin), but his own machinations present him as a satire of extreme religious convictions. Statues of Jefferson, Washington and Franklin (each bearing a symbol of a specific virtue) symbolize the blind worship of famous men and their contributions to the United States, while other figures such as Lincoln become demonized. At the same time, worker exploitation manifests in Jeremiah Fink, the carnie-like founder of Fink Manufacturing; when the player first encounters him at the raffle, he shows the dark side of human nature by awarding the winning number a first hit at an interracial couple. Notice the giant golden Fink statue and the rundown Shantytown where his workers reside; Fink practically controls his workers, as he pays them in Fink Tokens, which are only useful in the company store. He erected a monument to himself, a symbol of the financial empire he created on the toil of the common man; another scene beautifully illustrates the tight control he wields over Shantytown. This scene shows workers rising from their beds, a giant wheel behind them; the wheel dictates their lives by assigning specific times for work, leisure and other activities,

To round off this article, a few more games should be examined for their artistic merit. Bioshock Infinite, the third installment of the Bioshock franchise, takes place in 1912; Irrational Games really did their homework when it came to a somewhat accurate portrayal of the difficult times experienced by minorities and workers during the early 20th century. As far as art goes, Infinite really pulls no punches when presenting the racist ideas found in the time period; the bloodied corpse of Chae Lim is a visceral, frightening image to behold, a reminder that people of Chinese descent did not receive any respect at the time, for various reasons. The racial and social tension of Columbia echoes the general history of the United States; Zachary Comstock wished to create a religious utopia in the clouds, away from the “Sodom Below” (which he perceives to be the epitome of wickedness and sin), but his own machinations present him as a satire of extreme religious convictions. Statues of Jefferson, Washington and Franklin (each bearing a symbol of a specific virtue) symbolize the blind worship of famous men and their contributions to the United States, while other figures such as Lincoln become demonized. At the same time, worker exploitation manifests in Jeremiah Fink, the carnie-like founder of Fink Manufacturing; when the player first encounters him at the raffle, he shows the dark side of human nature by awarding the winning number a first hit at an interracial couple. Notice the giant golden Fink statue and the rundown Shantytown where his workers reside; Fink practically controls his workers, as he pays them in Fink Tokens, which are only useful in the company store. He erected a monument to himself, a symbol of the financial empire he created on the toil of the common man; another scene beautifully illustrates the tight control he wields over Shantytown. This scene shows workers rising from their beds, a giant wheel behind them; the wheel dictates their lives by assigning specific times for work, leisure and other activities,

To give a light-hearted counterpart, the LEGO franchise includes a number of licensed games, ranging from Harry Potter to Indiana Jones; their most recent outing, Lego Marvel Super-Heroes, lets players take control of a multitude of the comic company’s most popular figures. The digital medium allows for LEGO figures to move more fluidly, and seeing the miniature versions of such iconic characters as Iron Man and Spider-Man are a blast; the overworld map gets special consideration here, as a LEGO-fied New York City is yours to roam around in; it looks marvelous, no matter where you stand, and the free fall from the Helicarrier indeed gives a great sense of sheer scale. It may not be considered art on the same scale as the Mona Lisa, but LEGO Marvel demonstrates how great art can be produced for a commercial enterprise; they took great care in modeling the figures and giving them voices, and seeing them in action can bring a smile to one’s face.

It’s been quite some time since we first saw video games enter the market, and today’s generation of consoles show the enormous diversity of genres and games available for purchase; whether you’re into fighting games, RPGs or indie productions, there’s a release for you. The presence of independent games alone shows the great potential for video games to break free from self-imposed constraints (how many Call of Duty games do we need, anyhow) and offer some deep, artistically astounding works that show off what a game is capable of. We’ve seen major releases such as Batman: Arkham Asylum bring superheroes back into the limelight, but other games such as Child of Light and the upcoming PS4 re-release of Grim Fandango remind us that some of the most innovative works out there have premises outside the “norm;” the cult classic Grim Fandango, for example, incorporates the Aztec afterlife with film noir inspirations, resulting in a masterpiece of mood lighting and a great jazz score.

It’s been quite some time since we first saw video games enter the market, and today’s generation of consoles show the enormous diversity of genres and games available for purchase; whether you’re into fighting games, RPGs or indie productions, there’s a release for you. The presence of independent games alone shows the great potential for video games to break free from self-imposed constraints (how many Call of Duty games do we need, anyhow) and offer some deep, artistically astounding works that show off what a game is capable of. We’ve seen major releases such as Batman: Arkham Asylum bring superheroes back into the limelight, but other games such as Child of Light and the upcoming PS4 re-release of Grim Fandango remind us that some of the most innovative works out there have premises outside the “norm;” the cult classic Grim Fandango, for example, incorporates the Aztec afterlife with film noir inspirations, resulting in a masterpiece of mood lighting and a great jazz score.

The one real benefit of all the increased computing power that Moore’s Law gives us — and will continue to give us until about the year 2020 or so — is the amazing variety of art that can now be created and interacted with. Games may continue to evolve and change over time, but art is timeless.

Share

| Tweet |

Twitter

Twitter

The relationship is symbiotic you need big budget games like COD and GTA etc. to be able to make games like journey etc. but even those big budget games needed other successful games to exist. GTAs founding design house was DMA who later became rockstar north. They breakthrough was lemmings. The first GTA was nearly cancelled so many times it met none of its initial targets and the development was described as trying to nail jello to a kitten. Initially should of been on the Nintendo 64 and sega Saturn as well but was never released. But with design houses being so unpredictable and no guarantee that you will be in the same job next week it seems desirable now more than ever for experienced designers to work in small indie developers. Where GTA was created by 20 odd newbies to the industry, today it may of been created by 20 odd fully experienced workers. Certainly this is because of the power of the internet and consoles today. But internet has the biggest part to play.