Home A La Disneyland

by Estim20, HSM Editor

Imagine, if you will, it is the late 1920’s. It is the Roaring Twenties, a decade known in current popular culture as a decade of extravagance, excess, gangsters, and booze – and the Prohibition that helped bring it about. The Twenties bore witness to increased spending and a growing consumer culture, aided by a benevolent transition from wartime to peacetime economies (especially true for the United States).

Mass production fueled this economy, bolstering such products as the automobile, movie, and radio to such a state as the middle class can afford them. Radios became the first broadcasting medium, with movies entertaining the masses during this pre-Hays Code boom. Movies, on that note, jumped the gap from soundless, monochromatic affairs with accompanying music played live to ‘talkies,’ with even the first all-color film, The Toll of the Sea, released in 1922.

Jazz entered the mainstream, producing such long-lasting names as Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Jelly Roll Morton. Blues’ growth paralleled jazz with the likes of Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey. Women’s suffrage became law at the start of the decade as women’s roles in society transformed. All this was ironically framed by a decade also well-known for Prohibition and speakeasies, both of which spawned bootleg booze and the legacies of such gangsters as Lucky Luciano and Al Capone. The Great Gatsby, written in 1925, provided a fictionalized time capsule for the atmosphere of the decade it portrayed.

Born among all these culture giants was yet another (soon-to-be) famous name, and he didn’t even technically exist physically. He helped make his company a cinematic and animation powerhouse that stands today, without being a flesh-and-blood actor. His name became famous worldwide in the ensuing century, lasting into the 21st and even starring in a Square-Enix production. Ironically, his existence was due to the company the rights to another character (along with a handful of employees) to Universal Studios. Had the original creation succeeded, his replacement may not have found stardom.

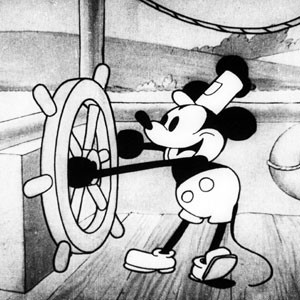

To spoil the mystery: in 1928, Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks created their runaway hit character, Mickey Mouse.

It’s not to say they sat on their laurels earlier in the Roaring Twenties. In fact, as mentioned above, Mickey’s existed was predicated by Disney losing the distribution rights to Oswald the Lucky Rabbit – along with four of his primary animators, excluding Ub Iwerks. Disney, in an effort to replace the ironically named rabbit, concocted Mortimer Mouse on a train ride to California, with Iwerks ironing out the designs provided and the name eventually changed to the more appealing Mickey Mouse.

In 1928, they concocted three shorts to star their new creation, with the third short Steamboat Willie debuting first. Steamboat Willie became famous not only as Mickey’s first released appearance but also as the first cartoon to feature synchronized sound, influencing its popularity. Its sister shorts were retrofitted to feature synchronized sound after their 1928 debut and re-released the following year.

During the 1930s, Disney procured a contract with Technicolor to produce all-color shorts, the first released in 1932. This helped pave the way for their first theatrical film Snow White – a risky gamble due to the budget inflating such that the film was worth more than the company itself and that feature-length animated films really hadn’t been a thing prior to Disney’s first magnum opus. Disney even had to mortgage his house to help finance the film, which (along with every factor) ballooned the cost to nearly 1.5 million dollars – a far heftier financial punch when you consider it started production in 1934.

The rest of Disney’s history is a fairly recognizable tale. Snow White fortunately proved an amazing financial success (along with its critical accolades), setting the stage for a series of animation films – and giving Disney a history of fairy tale fare. When box office sales dipped in the ‘40s, they found opportunity with the armed forces during World War II and television following the war, complimenting their animated fare during the Forties and Fifties with live action features.

The overall success of the Walt Disney Corporation up until mid-century led to its other highly-visible legacy – or legacies, if you consider the Seventies’ ‘sequel’ a sister project worthy of counting separately. In 1955, Disney opened the doors to Disneyland, a theme park filled with attractions designed around Disney property as well as rides with unique premises. You owe the existence of the tenacious earworm It’s A Small World to the naiveté of Disneyland’s grand opening – which, coincidentally enough, occurred in the same year Marty McFly traveled to in Back to the Future, because life sometimes likes such coincidences.

Disney’s ubiquity in the modern world is due in no small part to its endearing evergreen, Mickey Mouse – along with the business savvy of a man who people swear is still alive and in cryogenic slumber somewhere in his parks. Only a few characters command the same level of world-wide recognition and joy as the mouse (a list that includes, personally speaking, Superman, among others) and it says something to his lasting appeal. We live in a world where we can all come together in respect of an animated talking mouse in the same breath we used to praise original Coca-Cola over its devious marketing-borne off-spring, Coke II.

I love modern life, even with all its peculiarities.

But nonetheless, you are perhaps wondering why I am writing an introduction about Mickey Mouse for an article on a website born from PlayStation Home about said social MMO. It occurred to me this year that perhaps the best way to summarize the Hub system in a woefully-simplistic fashion is as such. It’s when a theme park isn’t a theme park, an experiment that failed to notice it just tried to make Digital Disney.

It has the trappings of a Disneyland structure and may benefit from capitalizing on it more. Sure, it isn’t exactly like Disneyland but Sony may have stumbled upon the means of creating a Sony-sanctioned digital theme park. To showcase where it might go had it gone fully in that direction, let’s view it from the standpoint that the Disney model spread its tentacles onto PlayStation.

Naturally this requires knowing what makes the theme park tick. Disneyland (and its sibling Disneyworld) is known for various features, ranging from actors in anthropomorphic animal costumes to long lines for the restrooms. At their core are their layouts, not limited to Disney’s foray mind you and highly recognizable: a park set-up via districts, each with their own particular theme. Each district holds attractions and various other entertainments designed around the theme, as well as cultural mores and advancements of the era. It’s why a journey to the Moon mutated into a journey to Mars.

Home utilizes a similar set-up with its Core Spaces, if without the roller coasters and bumper cars. The Hub system offers an overarching video game theme, contrasting Disney’s fantasy and adventure areas, but they perhaps don’t take it as far as they could. As it stands, they’re suited better for advertising other spaces and games, both on and off Home, rather than taking Disney’s approach.

So what would Home do if it follows this model? First, the Hub would serve as the expy of Main Street USA, if with fewer cues from the turn of the 20th century. It remains the first area guests will visit, designed such that it draws guests towards the piece de resistance – the gate towards the other districts of the Hub system, however they may be themed. Obviously with this being Sonyland, it won’t be modeled after Sleeping Beauty Castle, but something suitable must be placed here to attract attention.

Keeping in line with Disneyland’s architecture and planning, the Hub won’t host the most complicated attractions. It will serve as an information center, giving historical displays for Sony and Home, as well as social and store updates via built-in news boards. Anything you need to know, you can find here, helpfully placed somewhere easy to find and access. Basic advertisements will greet customers here as well, with the other themed areas providing more theme-appropriate adverts that may have more complexity to their design.

Any stores in the Hub are your Sony-specific stores, ranging from the non-licensed Home exclusives from Sony itself, as well as the heavily touted Exclusives line. These are the most common and least exotic fare, with such examples as t-shirts, jeans, shorts, and the like. As such, it’ll cater to a generic, every-town feel, if one more in line with west coast fashions given SCEA’s base of operations set in the west coast.

As such, the Hub will resemble a Hollywood-ized vision of the West Coast, especially California, in its architectural design. Pine trees and the beach are in great force, with buildings taking cues from appropriate west coast architecture, past and present. It’ll likely give precedence to the present so expect more Hollywood Hills and less Spanish missions.

At this point in the tour, people are ready to venture forward and see if Home lets them live a fantasy in digital form. Disneyland, if you recall, takes visitors across everything from Buzz Lighter’s space academy to pirates of the Caribbean, so it offers quite an exotic selection. Even in Home as it stands now, we can leave the womb that is the Hub and become anything from Edo-period samurai fighting oni to pirates on the high seas, battling it out for aquatic supremacy.

If the Hub System follows the Disneyland model, it would incorporate exotic locales once you leave the confines of Hub Street USA. Gone are the limitations of real life, replaced by the whimsy of fantasy, sci-fi, and any other genres the company may deem appropriate to design. For this, there is an easy way to go for designing spaces, which we already see in its actual form – if in comparatively limited capacity.

But a Home vis-à-vis Disneyland wouldn’t simply rely on sponsors to give it that fantastical level of whimsy – the Hub System itself should take greater lengths to encourage it. As such, Home will have the Hub System based upon video game genres. Given this is a social MMO for gamers (and, presumably, by gamers), it would help reiterate its focus group by making themed districts based on genres used in video games – a tactic we already seen in some fashion with Home as it is now. Adventure District is a step in the right direction, as is Sportswalk and Action District, but more can be done to make it a cavalcade of gaming tropes.

Let’s take an example. Adventure District is for the genre of games focused on pursuing adventures. Tomb Raider, Uncharted, and their cousins are the experience du jour for this space and technically it does satisfy that. It even hosted an Uncharted experience for the release of Uncharted 3. This attempt to bring in what gamers desire from a console is what’s needed.

What they could do to improve upon the experience is make it like a theme park, with some form of interactive attractions. The best base experience for this is Acorn Meadows, with its bicycling path and small-scale riding train. They can extend the experience to include more variety of attractions, ranging from comparatively simple (to console) games and even the occasional roller coaster or dark ride.

A Disneyland-like Hub System would thus include some non-licensed fare that would meet the theme imposed upon the space. With an Adventureland set-up, for example, you could create a safari cruise or ‘escape the wrath of dinosaurs’ experience, capitalizing more on tropes commonly used with the theme present rather than specific licenses. Sony can thus capitalize on their own creations alongside licensed fare that fits in with the districts.

Now making theme park quality (and length) attractions, especially when we talk about the roller coasters, may be impractical at best. Memory limitations may restrict features, given Home isn’t quite the technological powerhouse we can expect had they released it as a disc-based game, so we must make do with what Home can offer us. Fortunately, there is plenty it can offer under the Disneyland model if we emphasize its connection to gamers and gaming.

Bear in mind this isn’t restricted to the “MAKE MORE GAMES” mode of thought. However, it is a good start – and we can initially limit it to some basic, theme-significant fare that is easier on the memory limitations while offering easy ways to generate profit for Sony (and anyone else making these games). Namely we can take the ideas pioneered by Midway, Granzella, and Peakvox and create a Home-wide model for games.

Granzella, Midway, and Peakvox all offer free-to-play options for those on a budget while simultaneously offering means of adding convenience and speed to the experience for a price. Granzella and Peakvox especially offer expendable items (tickets and catalysts, among others, respectfully) as well as permanent boosts so long as you wear them (weapons and arcade boosts, also respectfully). This way, players can get a taste of these games and figure out if they play often enough to justify purchasing extras to boost their play.

Obviously upkeep is important for the persistence of Home. Money makes the world go round and Home needs it as life-support. Free plays may bring an audience, but pay options will bring in the cash. For this, there is a possibility for inspiration. Sony can generate revenue if it applies games with these perks in place. Taking cues from Granzella’s ticket system (and, by proxy, Midway’s ticket system), Sony can incorporate a ‘one size fits all’ currency, wherein one ticket may be spent in any game that uses tickets. This way the consumer isn’t expected to divvy their budget across multiple district-exclusive currencies.

Boosts and upgrades are, naturally, dependent on the games themselves. For this, there are numerous on and off-Home examples for pay-to-keep, permanent boosts Sony may utilize. Granzella uses a system where you must wear an item in order to benefit from its boosts – for example, weapons you buy for the Defend Edo game must be equipped prior to battle. The same applies to any armor; in a nice stroke of connectivity, many Granzella costumes provide defensive stats for Defend Edo, even if they aren’t made for the game.

As is the case with Peakvox, there are other means of offering expendable items beyond ‘pay one ticket to enter.’ When brewing pets in Peakvox Labs, for example, you can use catalysts to speed up the time required before an item finishes, as well as increase the level of ingredients you use to create said pets. In fact, higher level items (i.e. anything above level 30) require a catalyst to produce, so anyone hoping to create them all must catalyst away. Sony can thus take a cue from Peakvox and offer game-specific benefits or items that require spending some cash.

Then we get into the sponsored spaces, a staple for Disney and Sony alike. Disney has an advantage in the sense that it has (as of this writing) 85 years of its mousy mascot, along with everything else since Mickey’s debut. As such, Disney can (and, importantly, has) create rides and events for a multitude of products it owns. With such a library, Disney wouldn’t require stepping outside its licenses very often.

Sony, however, has plenty of third-party licenses released on the PlayStation 3 – many of which it does not outright own. When you’re dealing with popular franchises as Street Fighter, Uncharted, and Final Fantasy you will have to play negotiator to release costumes, games, and events based on them (rather than ‘inspired by’ them) into your social MMO. To that end, Sony has managed to convince a few companies into Home.

Sponsored spaces may (and have) become an important staple for Home’s audience, built upon gamers familiar with the games on the system. Being able to dress up and subsequently play as Lightning or Nathan Drake is enough in demand that it’ll get some money flowing into Home itself. The main issue will be getting money flowing to companies that own the licenses in question.

Disneyworld has the advantage in that sponsors can provide their own gear to sell into the theme park – and once you’re in the park, you’re at the mercy, generally speaking, of whatever the park has to offer. It’s more difficult to jump ship partway through and try another theme park if it doesn’t please you. After all, most major theme parks aren’t quite that close to one another and cost leagues more than anything Home offers just to get in. We’ve even ignored the travel expenditures getting there.

However, Home does have one advantage in that it doesn’t require companies to work from the ground-up with the engine. Also, nothing is physical; they don’t need to pay for cost of materials for clothes in the sense that they won’t pay for every single person wearing one of their shirts. Sponsored items thus gain a perk when they are digital.

Sponsored spaces are a similar deal: with no need for ground-breaking and physical buildings, a company can develop a digital space that exists solely in the social MMO. They can easily tweak and adjust it, at least when compared to something physical, and add what they need for anything from events to advertising.

So far this has shown how Sony can adjust the gaming foundation behind Home. Improving the gaming experience, from an entertainment and financial standpoint, are undeniably important, but there are other methods Sony can borrow from Disney’s mid-century example. Disney didn’t exactly stop with providing rides and games for kids of all ages, since what’s the fun in that, am I right?

In the Venn diagram that is Disney and Home, they do overlap in one other feature: events. Disney’s theme parks across the world not only host events; they cater to holidays popular in each country. It’s why you don’t see Japanese-specific events in Florida – well, besides the inherent risk of a crocodile deciding to chew on a Bon Odori festival.

Home follows suits, typically for the holidays and sponsored events. As such, in any given year you may see anything from Talk like a Pirate Day and Halloween to Uncharted 3 (The Adventure District Experience) and the Kikai Empire Invasion. This practice may not change in the same way as the Hub System itself would, with a few notable changes in place.

First off, there may be more ‘canned’ events in the sense that Sony may not always create something new each year for holidays. We saw this before in Home, with the Pumpkin King event, but from time to time you may see Sony reproduce a parade or two, along with a few mini-games. Creating a few basic treats for each holiday that don’t bog down the servers and can repeat every year will ensure that people will earn the chance for the rewards no matter how long they’ve been on Home.

Secondly: they can also take cues from Disney in modifying existing ideas and expand upon them, alongside creating new ones as time goes by. One possibility is in addition to creating a few basic events for the Hub and its kin, Sony can also create space-specific events that either get expanded and modified each year or replaced with a new experience instead. This way, lethargy and rot won’t set in and users won’t be bored with the same routine every holiday season.

Sponsored events will likely continue, regardless of Disney’s use (or non-use) of this tactic. As we seen with the Kikai Empire Invasion, major events are popular, if occasionally difficult to turn a profit, and do generate buzz for the major spenders. Companies that invest in Home may offer events of their own, in spaces of their own, with unique rewards appropriate to the event in question. Adding unique costumes that aid in the event (or are required to access the event) will help generate some revenue and gauge what people are willing to pay for.

The expectation of ‘newness’ will be a prominent issue for Home even under the Disneyland model, as there is one fact of life you can’t escape. Life changes and everything around it changes to match. In Disneyland, we see rides come and go as technology (and safety regulations) improve, alongside changes in cultural viewpoints. Once upon a time, it was considered exotic going to the Moon; now it’s passé and Mars is our new frontier.

Similarly, new licenses are released. For Disneyland, movies are a significant source of licenses. A movie once on everyone’s lips will eventually stop being topical; as a result, a ride based on said movie will turn old-hat eventually as well, if technological issues haven’t cropped up by then. Disneyland thus eventually replaces rides for those based on more recent films – often animated films, given Disney’s reputation and the theme park’s desire to look family-friendly.

Home, similarly, can benefit from advertising more recent games by switching out events and spaces as newer games are released. We already witnessed spaces removed but not quite at the rate of Disneyland removing rides. It may benefit Sony to nix game spaces sooner, but they also have another route they can take due to the nature of gaming: sequels!

Sequels are a common sight in video games, as much as they are in films. Home can reap the potential benefits by updating spaces based on popular franchises. Resident Evil 5’s space could have mutated into Resident Evil 6, for example, or Street Fighter IV’s space could’ve incorporated the additional characters from re-releases of the game. Likewise, the Final Fantasy series can be increasingly represented as more games enter the series.

There are two possibilities for companies when it comes to offering licensed fare: company-themed districts (think NAMCO Museum) or game-specific spaces, if not a combination of both. Companies that opt for company-themed districts may take Juggernaut’s example with Serenity Plaza or with Heavy Water’s D20 – a showcase for all things ‘insert name here.’ Stores will showcase licensed-themed fare, updated as the company sees fit with newer and older releases alike and interactive elements can range from bonuses for playing related games (a la Street Fighter IV’s throne) to mini-games and so forth.

Finally, let’s talk exclusivity. Home is no stranger to exclusive spaces and items, especially from Sony’s side of the equation. Disney also has its own unique areas that are difficult, if not impossible, for the average guest to view. These areas range from Club 33 to the suite in Sleeping Beauty Castle, known for the expense required – also something of which Home is no stranger.

The Sonyland version of Home may emphasize gamer-style exclusives tucked away inside each district, based (as you would expect) on the theme. They may be anything from socializing lounges (to get away from the chaotic hustle outside) to unique gaming experiences for those who rocket up leaderboards. They parallel Home’s own evolution of the exclusives market, from the Mansion to x7 to Lockwood’s own creation. Each serves a certain segment of the population and offer similar (and, in some cases, unique) perks.

The main difference, as stated above, is that Home will cater to gamers first and foremost in this system, as well as offering various themed exclusives so that people may identify their own tastes. Each district’s exclusive area will be themed appropriately, with few surprises regarding what you’re getting into. This adds the benefit of catering to a myriad of tastes without suggesting that the exclusive content is ‘for everyone.’ Plus entry will be catered to the area as well, requiring either certain items or, if games are the factor, certain scores (think the poker tournaments for this). To that end, it may be anything from exclusive spaces to exclusive events.

In Summation: A Quick Peek into Sonyland

Okay, so what may this look like ultimately? Will Home be anywhere near what it is like today? What features would this alternate universe retain? Well, let’s take a look into the crystal ball and summarize Home envisioned as ‘Sonyland.’

The Hub system remains very similar, except Pier Park (and potentially Indie Park) is gone. In its place are more video game genre-specific districts, retaining the names Adventure District and Sportswalk. Action District may be kept as named, with smaller subsections dedicated to the licks of platformers and FPS titles. Home will thus become a haven for gamers of all types, without needing to create exclusively license-driven material. Think of the Hub spaces as how Granzella is to anime in that regard: tropes aplenty that are license-free.

Sony events will be advertised via Hub’s gateway square and will most often utilize core spaces as they will be under the system. New, temporary spaces will crop up as needed, emphasizing convenience and exploration of the Hub system (as well as, cough, the stores, end cough). Increasing the size of the core spaces will happen with time, as Home grows and necessitates extra space for more events, stores, and so forth.

Very little regarding second and third parties will change in Home under this model. Presence of licenses will be negotiated as per normal, with potential for growth via including future sequels in Home. Resident Evil 5’s space would include or be overtaken by Resident Evil 6, for example. Second-party developers will remain in the scene, as well, meaning the likes of LOOT will remain present in Home.

Second and third-party developers will remain as free to develop items as they are now, similarly. Events are held at their discretion, if still restricted any agreements between them and Sony. Their presence will be predominantly in their own spaces, with the occasional event stretched over into the revised Hub system. Companies developing video games can thus advertise their games via the appropriate district (or districts) with any items or events deemed useful for sale and/or use.

Store access in the Navigator remains available, but Sony increases specialization as it pertains to the genre districts. Threads and Costumes will become overarching headers, with first party (i.e. Sony) themed clothing in their respective subsections. Companies sponsoring spaces will be allowed to create their own stores – anything they make for district themes will be coupled under the appropriate subsection or under their store, depending on the exact deal created by

Games and events utilize the revised Hub system as best as possible. Third party companies aren’t restricted to the Hub’s genre districts but Sony will definitely make the use of it. Home will continue to see Home-exclusive games, built from the ground-up to use what Home has to offer (as is the case now).

Games and events (especially games) will also be switched out as necessary, whether they are first, second, or third-party sources. Major ones, equivalent to Mercia or Sodium, may be expanded rather than out-right replaced, but games small enough to justify replacing may be removed for new material. The rotation period for such replacements will likely be decided by Sony, with some leeway given to third-party developers.

First-party games will utilize a universal token system, used as needed by games across every district. Third-party games aren’t required to use them, given they aren’t tied to first-party regulations, so they may introduce their own payment system and items. Boosts and other perks are left up to the games and don’t require a universal system for use. Rewards divvied up by winning remain the same as it is now (i.e. whatever suits the game, in terms of what they are, how you earn them, and if they require any purchasable items to earn in the first play).

Exclusive spaces will be designed around the various districts, each with their own entry requirements. This will distinguish the spaces from games in the districts, with an attempt to make the requirements intuitive. Exclusive item stores won’t be as necessary given each district has its own store as it is; as such, ‘exclusivity’ will be restricted to gaining access to areas once blocked off.

In Conclusion

This is but one possible look into another Home, an enterprise overshadowed by a different methodology. It actually bares some considerable resemblance to Home as it currently is, but with some differences emphasizing other concepts. It gives the impression that Home missed out on the whole ‘theme park’ boat.

How else would Home have turned out had it taken a different direction? There is a multitude of inspirations Home could’ve taken; just imagine what it would’ve been like if it decided on another route.

Share

| Tweet |