Mushishi, Weather Report, and Home

by RadiumEyes, HSM team writer

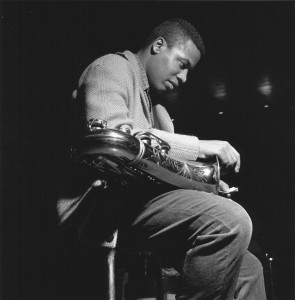

As I write this introductory paragraph, I have Weather Report’s “Milky Way” playing in the background. A Shorter/Zawinul composition, it opened the band’s eponymous first album from 1971 and it has this beautifully ethereal quality to it that can be very relaxing for listeners. The release contains some of Weather Report’s best material; overall, a great work to listen to, with Shorter (one of the band’s co-founders) showcasing his great talent as a bandleader and sax player.

Weather Report, a rather avant-garde release, reminds me of how complex and seemingly conflicting Home can be. Home and other, similar social platforms allow people from all walks of life to interact, and as a result, it develops into a microcosm of real life. You have everyone from kind souls to trolls on the social spectrum and it can be rather confusing at times to deal with it all. Discordant rhythms coincide with more upbeat songs (listen to “Umbrellas” and “Orange Lady” for a great example of such a contrast), and listening to the entire album can be disorienting – the band doesn’t shy away from creating some more difficult-to-play songs, and jazz offers a splendid avenue for experimentation.

Home offers a similar form of disparity among its individual elements; sometimes, one can find a place that encompasses the tone of the Lydian mode, while other times can feel rather Locrian. With everything we have available to us, from the earliest content offered in closed beta to more recent fare such as Nostalgic School Days and the curious Noob-Away spray (which made its Home debut in the previous week), the PlayStation 3’s social platform can feel disjointed, with no particular theme connecting every single space together.

However, aesthetic discontinuity allows for some greater freedom of movement and self-expression; worlds seem to collide, and the result is a unified whole where one can traverse disparate areas rather seamlessly, and observe how an aesthetic “tune” is constructed within the confines of a social application. Each space has its own unique virtual aura to it, and an accompanying tune can complement it. The world of Home offers so much that positive and negative experiences inevitably develop while on it.

Let us move on to another subject where the “strange” becomes an integral part of the production’s universe: Mushishi. The sublime beauty of this anime stems from both the environment and the interactions between its protagonist and those that need help in dealing with mushi, the representation of Life Itself. Throughout the series’ run, Ginko (the eponymous mushishi) encounters numerous instances of the peculiar in Japanese society, with the enigmatic mushi being the cause of some disturbance in society. Each case he tackles is fairly isolated physically, but each one has a connection: the River of Life, or kouki, running through the veins of the planet, itself a collection of mushi. This river cannot be seen by humans under traditional circumstances – people “contaminated” with the primal forces of Life can, however, and this can take a toll on a person’s well-being.

Each individual Ginko meets has a story to tell, with the overarching theme of isolation and “otherness” that comes with being connected with the mushi. Wherever he goes, Ginko finds himself in villages dotting the countryside, each rustic in quality and containing architecture typical of the Edo period and earlier; these villages all operate as distinct “worlds” in their own right, and offer unusual challenges for the mushishi to overcome. Is he successful in “saving” the afflicted individual from the mushi that brought about such a dramatic physical change? Not always; occasionally, a person becomes part of the mushi, an irrevocable change.

Each individual Ginko meets has a story to tell, with the overarching theme of isolation and “otherness” that comes with being connected with the mushi. Wherever he goes, Ginko finds himself in villages dotting the countryside, each rustic in quality and containing architecture typical of the Edo period and earlier; these villages all operate as distinct “worlds” in their own right, and offer unusual challenges for the mushishi to overcome. Is he successful in “saving” the afflicted individual from the mushi that brought about such a dramatic physical change? Not always; occasionally, a person becomes part of the mushi, an irrevocable change.

That Ginko cannot help everyone, even if he does his best, reminds us that not everything can be positive – the world can be an odd place, and only through working with it and its vagaries can one achieve a good life. With Home, interactions can be quite a hassle, and knowing how to handle a situation (either pleasant or volatile) requires tact and grace; everyone you meet contributes to your overall experience on the server, for better or worse, and delicately approaching each encounter with a good amount of poise and emotional understanding will do wonders for one’s continued participation in a virtual environment inhabited by people from across the globe.

Mushishi, in many respects, reflects the Home experience. From people who chase rainbows (literally, in the case of episode seven), to a girl blinded by mushi that inserted itself into her eyes, characters introduced in the series all have different problem that they must overcome in order to “move on” and see the world without any further issues. Each episode ends with Ginko resolving any source of personal physical conflict for those he meets; however, when he leaves, he implicitly states that the person he assisted must figure out what to do from here on out. One man can only achieve so much – after he does what he can, it’s up to the other person to take the reins.

Of course, the series presents such life lessons through the lens of the “strange,” meaning every concern presented in each episode has a level of idiosyncrasy to it (thanks to the presence of primeval life); but one begins peeling back the layers, and sees the thematic core of the show – connection with nature and interpersonal relationships. Ginko’s own life began when Nui, a female mushishi, adopted him years ago; it’s noteworthy to mention that Ginko initially went by the name Yoki, and his current name stems from the very mushi that entered his body, turning his hair white and his eyes green. Nui came into contact with the same type that would later affect Ginko, and her appearance closely resembles Ginko as we know him in the present; with Ginko, he took his current name because the mushi that swallowed him up took some of his memories, which included that of his original identity.

Of course, the series presents such life lessons through the lens of the “strange,” meaning every concern presented in each episode has a level of idiosyncrasy to it (thanks to the presence of primeval life); but one begins peeling back the layers, and sees the thematic core of the show – connection with nature and interpersonal relationships. Ginko’s own life began when Nui, a female mushishi, adopted him years ago; it’s noteworthy to mention that Ginko initially went by the name Yoki, and his current name stems from the very mushi that entered his body, turning his hair white and his eyes green. Nui came into contact with the same type that would later affect Ginko, and her appearance closely resembles Ginko as we know him in the present; with Ginko, he took his current name because the mushi that swallowed him up took some of his memories, which included that of his original identity.

From then on out, Ginko carried on as a mushishi, essentially resuming Nui’s work for her. Nui willingly sacrificed herself to the Tokoyami (fish altered by the Ginko) in order to help the young Yoki find his path and learn how to escape the fate that befell her – she became a Tokoyami herself, and eventually faded away. This sets the stage for Yoki (now under a new name) to rome the countryside to offer his services to those desperately in need of it; his encounters find him seeing the deleterious effects of various mushi on people, and he must intervene before further damage would come to them.

This aspect of Mushishi reveals the travails of life and chance encounters – everyone you meet have their own personal struggles, and it takes great effort to resolve them and return to “life as usual.” Home can be exasperating in its own right – everyone can be the Ginko in their own story, seeing various people along the way, making friends and helping them with any issues they might have. Life doesn’t come with a guarantee of complete safety from strife, and Home is no different; people from different social backgrounds intermingle, and with that socialization comes the inevitable clash of personalities who see Home differently. Oh, you’ll see trolls here and there, as incisive behavior occurs on practically any platform that allows for worldwide interaction, but they’re not insurmountable – like the mushi, people who behave badly, and disrupt social harmony, can be dealt with tactfully.

Ginko shows how complicated life can be, and a sober-headed approach to the disparities of one’s environment can benefit everyone. Home exists as a microcosm of life itself – it may very well be an inadvertent digital mushi in its own right. No one has the exact same experience with it, and as it constantly changes on a weekly basis, one’s continued participation will result in new memories and stories to tell. Take it from Ginko and Weather Report – life is full of surprises, some of them dissonant and unusual, others pleasant and halcyon. What one can achieve through the power of imagery and music is incredible, as words are no longer necessary to convey a particular emotion or tell a tale. If you listen to something like Weather Report or Wayne Shorter, then move on to Cecil Taylor or Sun Ra, one can paint different mental pictures; the artists mentioned all have their own unique sound, and each song they play has its own thematic structure that carries the melody to its conclusion.

Home is like that in practically every way. It produces visually what great musicians do with compositions, and each space (both public and private) becomes a new scene for a user’s individual tale. Listen carefully, and the sounds and sights of life come alive. Take Granzella’s Tea House, for example: here is a locale steeped in history, connected indelibly to the tea ceremonies begun by eminent practitioners such as Sen no Rikyo; the sounds of crickets and the clacking of the shishi-odoshi bring to mind the simple pleasures of life, where one can meditate without any distractions. Mushishi and Weather Report offer that sort of meditative mood – they don’t bring attention to themselves, allowing the story to unfold naturally without any adornment.

Share

| Tweet |

Twitter

Twitter