Like all areas of science, neuroscience has to emphasize reproducibility. Datasets from imaging studies are expensive to obtain and cumbersome to share, and published papers often provide only the vaguest details about how the data were analyzed.

Project on Scientific Transparency

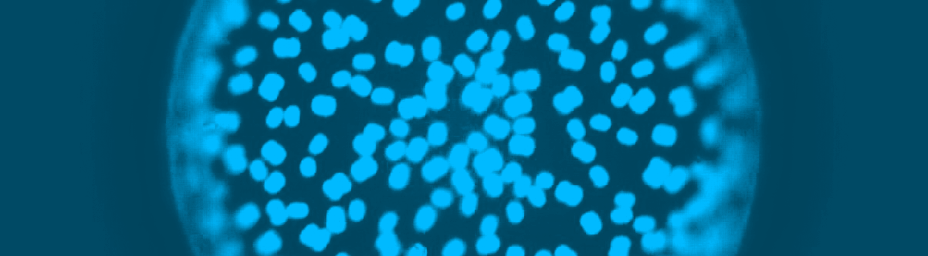

Signals between brain hemispheres are carried by millions of long-range neural fibers called axons, which form a visible and large structure called the corpus callosum. This magnetic resonance image (MRI) shows some of the largest groups of axons in the corpus callosum, colored according to the cortical regions that they connect. In the last decade, researchers found that individual differences in the yellow-colored tract correlate with a child’s reading ability. This observation is a topic of study and a source of hypotheses for how we might help children who have difficulty learning to read. MRIs are one type of data shared on SciTran.

“Papers often claim, ‘We used custom in-house software’ — as if that’s a description of anything,” says Brian Wandell, a neuroscientist at Stanford University in California. “It’s very hard to make sure the implementation the author wrote about is right.”

The Project on Scientific Transparency, directed by Wandell at Stanford, aims to change all that. “The current model is that you do your work and publish your paper, and then if you’re not too exhausted at the end, you might put your data into a centralized repository,” Wandell says. “We’re trying to create a model in which people are surrounded by the tools of sharing, reproducing and computation from the first moment they get data.”

The project has created a data-sharing platform called Scientific Transparency (SciTran) that instantly archives all data obtained by the approximately 500 users of Stanford’s shared magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines. “There are tools that start from the very first time you push the button on the MRI scanner,” Wandell says. Although researchers control access to their own data, sharing with others is easy. Scientists can search through the data — there are already more than 70,000 scans from 9,000 individuals — to identify potential collaborators, for example, or to find control data for an experiment. Wandell is working to install SciTran at other sites, including Indiana University and the University of California, Davis, so that scientists can share data across institutions.

Wandell and his collaborators are now in the process of integrating validated computational tools into SciTran — for instance, a Web-based interactive computational environment called the Jupyter Notebook (formerly the IPython Notebook), created by Fernando Perez of the University of California, Berkeley. This platform, which allows researchers to combine code, data and plain English explanations in a single dynamic website, is like a “living, breathing notebook,” says Alex Lash, the Simons Foundation’s chief informatics officer — one that can be shared with collaborators simply by sending them a link. The ultimate goal, Lash says, is for researchers to start including links to notebooks in their published papers, so that interested readers can see the detailed protocols that were used to analyze the data.

As a proof of concept, the Simons Foundation is working to upload imaging data to SciTran from about 200 families in the Simons Variation in Individuals Project, a database of families in which at least one individual has a copy number variant in the 16p11.2 chromosomal region, which is strongly linked to autism and other developmental disorders. The foundation is in discussion with SFARI Investigator Randy Buckner of Harvard University, whose laboratory performed one of the analyses of the neuroimaging dataset, about the possibility of representing the study’s methods in a Jupyter notebook. “This is a difficult-to-acquire dataset about families with a very specific genetic deletion or duplication; there’s probably a lot more we can learn from it if other investigators were to analyze it in different ways,” Wandell says.