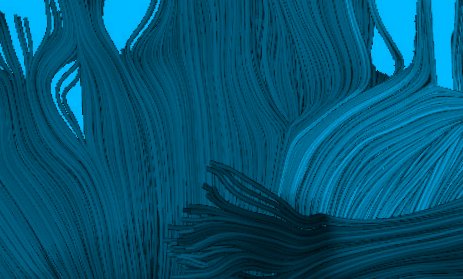

Diatoms are microscopic marine organisms that carry out photosynthesis and form the base of most marine food webs. Credit: Armbrust Laboratory

The ocean is alive, through and through, and not just with plants and animals that we can see. Every teaspoon of seawater contains millions of microorganisms that we are just beginning to understand.

Launched in July 2014, the Simons Collaboration on Ocean Processes and Ecology (SCOPE) aims to advance our understanding of the biology, ecology and biogeochemistry of the microbial processes that dominate the global ocean. The collaboration, now composed of 16 investigators working at Station ALOHA, about 60 miles north of Oahu, Hawai’i, in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, studies an ecosystem representative of a broad swath of the North Pacific Ocean.

The ocean’s billions of microorganisms, which together compose the ocean’s microbiome, depend on one another and on the ecosystem as a whole for healthy functioning. Therefore, study of the ocean’s microbiome on site is essential. And a combination of recent technological advances is making in situ study of the ocean’s microbiome possible.

New robotic submarines, controlled remotely by SCOPE investigators, will enable more in-depth examination of the open ocean and collection of new types of data. Novel genomics technologies will allow faster and more accurate genome sequencing of microorganisms. And advances in computer modeling facilitate management of new and massive amounts of data, which can then be analyzed to create models of how microorganisms may biochemically and ecologically function together in the ecosystem.

Hawaii Ocean Time (HOT) Series Program

For the past 27 years, HOT has tracked more than 40 critical ocean parameters in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, training dozens of young scientists in the process and creating one of the most thorough and long-term studies of the physical and biogeochemical parameters of the ocean to date.

Ocean Particles Big and Small

Sediment traps collect microscopic sinking particles and tiny aquatic life forms. This DeepDOM cruise in the South Atlantic Ocean illustrates the methods involved in harvesting and analyzing these important biomaterials.

Using these new technologies, SCOPE investigators intend to shed light on some fundamental questions of microbial oceanography — how gases are absorbed into the ocean from the atmosphere, how matter is transported to the deep sea, and the roles of microorganisms in fisheries and energy transfer.

“Having the right scientific tools, being able to gather the right sort of data, and being able to model how these complex systems work is becoming possible for the first time,” says DeLong. “Often it’s at the interfaces of disciplines that discoveries are made.”

To this end, the collaboration brings together experts from diverse disciplines — from scientists who study specific microorganisms to researchers who create mathematical models of organisms’ complex interactions — to shed light on fundamental questions of microbial oceanography. SCOPE held its inaugural annual meeting in New York City in December 2014, allowing investigators to meet and learn about one another’s areas of expertise. In shaping the collaboration, DeLong, Karl and the SCOPE steering committee selected investigators not only from a variety of disciplines, but also at different career stages. “We wanted to have a structure that is conducive of a long-term approach,” says Karl. “These problems are multigenerational, so we wanted a collaboration that is multi-generational as well.”

It is hoped that by working in concert, SCOPE investigators will create accurate models of microbial processes. Once these models are developed, the collaboration aims to conduct perturbation experiments of whole ecosystems using robots, ocean sensors and remote sampling. These experiments could enhance researchers’ understanding of how human activity affects ocean nutrient levels and many other eco-system factors.

“Nobody is looking at the microbial processes of the ocean as closely, as intensively or as collaboratively as we are, so we believe the collaboration will be a model for other programs in the future,” says Karl. “After a couple of years, we might be rewriting the ocean textbooks.”

DeLong adds, “Once you understand that the ocean — Earth’s largest biome — is a complex living thing, then it is, from a fundamental knowledge perspective, essential to understand how it works.”

Big RAPA

Experience the scientific process and significant discoveries from this month-long oceanic voyage from Chile to Rapa Nui in 2010.