Mirvat Sayegh, 23, gazes outside of her room at the Casal Damiano guest house in Campoleone, Italy. Sayegh is one of the 23 Syrian refugees living at the guest house as part of a humanitarian mission sponsored by an ecumenical partnership between Italian Christian organizations. March 15, 2016. (Religio/Lora Moftah)

CAMPOLEONE, Italy – “Bismillah,” the woman in the headscarf whispers, invoking the name of God in Arabic before pouring milk out of a pitcher into a baby’s bottle. Beside her stands a woman, also a mother but not veiled, waiting for the pitcher of milk. They exchange smiles as the woman with the headscarf passes the pitcher over after filling the bottle.

The two mothers, one a Muslim and the other a Christian, are standing in the brightly-lit dining area of a guest house called Agriturismo Casal Damiano, located in Campoleone, a sleepy agricultural town 30 minutes south of Rome.

Despite coming from different religious backgrounds and cities in Syria, Wala Jaber and Georgina Sayegh now both call the Campoleone guest house home. They will be living side-by-side for the next six months– and raising their two young toddlers there together.

The children, born just a few months apart, have become playmates and are sharing brightly-colored toys near the entrance of the dining area. “Bambina! Bambina!” Sayegh’s toddler George shouts in Italian as Jaber’s daughter Rahaf begins crawling past him into the foyer. Jaber looks up at the call. Before she can react, Sayegh has already hurried to scoop up Rahaf. She passes the baby to Jaber.

Though she’s only known Sayegh since late February, Jaber already feels like she is family. Both families fled Syria’s civil war for Lebanon and now they are sharing the experience of starting their lives from scratch in Italy.

“We are family now,” Jaber said of her new Christian neighbors. “Religion does not separate us. We treat each other with respect, thank God.”

Rahaf, the youngest of the 23 Syrian refugees living at the Casal Damiano guest house, being held by her mother, Wala Jaber. March 15, 2016. (Religio/Lora Moftah)

The Casal Damiano guest house is playing host to 23 Syrian refugees, among them Jaber and Sayeghs’ families. The families arrived in Italy in late February thanks to the efforts of an ecumenical partnership between Italian Catholic and Protestant organizations.

Italy is back at the center of the migrant crisis following a European Union deal implemented earlier this month that could see a new wave of migrants attempting the perilous voyage to Italian shores. The renewed pressure comes in the midst of continued paralysis within the Italian government about how to handle the crisis.

In the face of this paralysis, the Waldensian church and the Federation of Evangelical Churches in Italy, both Protestant church organizations, together with the Catholic Community of Sant’Egidio have joined forces to create a legal path for refugees to enter the country.

This pilot project, known as Mediterranean Hope + Humanitarian Corridors, aims to bring 1,000 of the most vulnerable refugees from conflict zones in the Middle East and Africa to Italy on special humanitarian visas. It’s the first project of its kind to make strategic use of an article from a 2009 E.U. visa regulation that permits a limited number of emergency visas for particularly at-risk refugees. The visas, however, are only valid within the national borders of the country responsible for issuing them, rather than the E.U. as a whole.

The organizations’ representatives work on the ground in countries like Lebanon, one of the primary hosts of fleeing Syrians, to identify the most vulnerable refugees. From there, they vet them and facilitate their safe passage and resettlement in Italy.

The main objective is to prevent refugees from attempting the treacherous Mediterranean Sea voyages that left more than 3,700 people dead in 2015, according to the International Organization for Migration. “We had to find ways to find ways to get these people in without forcing them to take the trips of death on the sea or at the border,” said Claudio Betti, a top official with the Community of Sant’Egidio.

Sant’Egidio, in partnership with the Waldensian Church, has been working with the Italian government since 2014 to develop the project and they hope that the modest effort can serve as a model for wider-scale action on the crisis.

Outside of the Casal Damiano guest house in Campoleone, Italy. March 15, 2016. (Religio/Lora Moftah)

The Campoleone families are part of the first group of 100 refugees to arrive in Italy through the program. On an afternoon in early March, the families were gathered around tables facing a representative from the Waldensian Church and an Arabic-language translator. As their host, the church is taking an active role in helping the refugees integrate into Italian society. On the agenda that day: language instruction.

“Your Italian lessons will be the key,” Giulia Gori, the Waldensian representative, explained in Italian while Moez Chamkhi, an Italian of Tunisian background, translated into Arabic. “The ultimate aim is to help you get jobs.”

One of the Muslim women at the table raised her hand to ask whether her headscarf might pose a problem for employers in Italy.

Gori and Chamkhi deliberated for a moment before Chamkhi responded. “Some companies don’t have a problem with it and some do,” he said, explaining that their group would make an effort to help find appropriate employment matches.

Jaber is personally not concerned about her headscarf or her religion getting in the way of her transition to life in Italy. While many Muslim women in Europe complain that they have been victims of discrimination, Jaber says that everyone she has encountered in Italy has been respectful and welcoming. “That’s what I like about being here. I have freedom to wear the hijab or whatever I want,” she said.

Her bigger concern is about her ability to master Italian. Learning a new language is already difficult on its own, she said. But watching Rahaf is also a full-time job. She wonders how she’ll be able to commit herself to her new studies while also taking care of her baby.

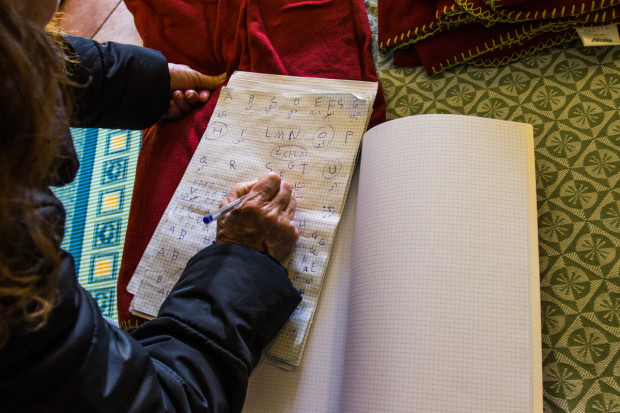

Badia Sayegh looks over a sheet of paper where she has begun practicing the Latin alphabet. Language instruction is a key part of the Waldensian Church’s efforts to integrate Syrian refugees in Italy. March 15, 2016. (Religio/Lora Moftah)

Gori, who serves as a program coordinator for the project, acknowledged that the challenges will likely be steep for many of the refugees. But she also pointed to how the Waldensian Church is making an effort to mitigate some of the challenges of integration. “We are trying to involve the local community as much as we can and we already have good results.”

Part of this has meant soliciting donations from local businesses for things like bookshelves and toys. It has also meant coordinating visits between members of the community to the guest house– which is run more like a bed and breakfast than a refugee center– in order to build personal connections.

The bigger challenge will be to scale up the program, according to Sant’Egidio’s Betti. “Expansion is a political issue,” he said. “Europe doesn’t understand [the project]. Italy is only beginning to understand it.” Like the Waldensian Church, Sant’Egidio is helping to finance the project through the public funding it receives from the Italian government.

As intensive as their efforts have been, they do not begin to address the scale of the problem, which saw more than 1.3 million people register as asylum seekers in Europe last year, more than double than that of the previous year, according to data compiled by the E.U.’s statistics agency Eurostat. An estimated 30 percent of these asylum seekers are from Syria.

European governments have struggled to reach a consensus on how to handle the crisis. Earlier in April a deal was implemented that would send migrants in Greece back to Turkey in an effort to deter new arrivals, an initiative that has been criticized by migrant advocacy organizations and rights groups. Following the blockade of the Greek migration route, fears are growing that migrants will increasingly turn to the dangerous sea route from North Africa to Sicily, increasing pressure on Italy to act.

In the absence of a broader agreement, the Waldensian Church and Sant’Egidio have pushed ahead with their own small-scale effort. Despite its limited impact, they see it as an imperative based on their practice of Christianity. The Waldensians reserve almost all of their government funding for charitable activities while Sant’Egidio has become legendary in Rome for its efforts to feed the homeless.

Though their efforts to aid refugees are religiously-motivated, they are not meant to change people’s minds about religion, according to Gori, who argues that both church groups favor a “light touch” when it comes to communicating their religious principles. “For us, Muslim and Christian weigh the same,” Gori said.

But being a Christian doesn’t hurt in Italy, a country that houses the Vatican, the headquarters of the Roman Catholic Church. For the Sayegh family, their Catholic faith has helped to connect them to the community outside of the guest house’s walls in a way their Muslim neighbors, who primarily pray in their rooms at the guest house, haven’t been able to.

The Sayeghs visit the church of San Giovanni Battista nearly every day. It’s a 20 minute walk from Casal Damiano. The fact that she doesn’t understand the service doesn’t bother Mirvat Sayegh, 23. Just being in the sanctuary relaxes her, she said. Besides connecting her to her new community, being in church also, in a strange way, connects her with home too. The hymns are the same as the ones sung back in her church in Aleppo. “They’re different words, but the same melodies,” she said.

Her mother, Badia agreed. She still remembers the first service they attended at the Italian church. It was the first time since her arrival in Italy that she felt calm. “It eased my suffering,” she said while clutching the crucifix around her neck. “I sat listening to the priest and did not understand a word but,” she said, moving her hand to her heart, “I felt it here.”