Reflection: Trouble on the Mount

By Tammy Mutasa

JERICHO – The majestic monastery that stands balanced on the cliffs of the Mount of Temptation overlooking Jericho is one of the Holy Land’s most tempting tourist sites. It is not only the place where an important part of the Christian story was played out; it is also a destination for peoples of many faiths. But not everyone had the same access to the Mount of Temptation on a day when my friend Josh and I visited in the early spring.

A stern monk guarding the Greek Orthodox monastery atop the mountain wagged his finger as we approached the heavy metal door of the monastery and said, “Only Orthodox.”

This was how we were greeted after we had just finished riding a rickety old cable car which I was certain would plunge us hundreds of feet to our death when it became windy on our way up the mountain. After the cable car deposited us near the top of the mountain, we staggered another 20 minutes after up the bare, rocky and steep slopes to the monastery. We were tired; panting for air; and sweaty from the sun beating down on us. Only now to be rejected at the door?

There was no way in hell we were going to let the skinny aging monk stand in the way. For many of us, there was no other time to ever return. Not in the foreseeable future.

The sacred mount is the place Christians believe, as told in Matthew 4:1-4, that the Devil tried to tempt Jesus as he fasted for 40 days and 40 nights before beginning his ministry.

The monastery, with its commanding view of Jericho, sits atop of the actual cave where the temptation happened, according to Christian belief. It was in this spot that the Devil said to Jesus:

“If you are the Son of God, command these stones to become loaves of bread.” But Jesus answered, “It is written, one shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of God.”

This incident is symbolic for me as a Christian because like other places we visited on this trip—the Sea of Galilee, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the Mount of Beatitudes—the Mount of Temptation symbolized a direct and tangible connection to my Christian faith. It is faith manifested. So, to forbid me, as a Christian, to see this holy site is to forbid me from seeing a significant memory of Jesus. It would be ludicrous.

We had to get in.

After the monk ushered in a group of Russian Orthodox Christians staying at the monastery, the rest of us plopped down in front of the metal door and thought:

“Let’s wait it out, the monk will come back.”

At least 30 minutes went by and some of the other Christians grew weary so they thought of another plan: banging on the doors repeatedly. It worked. The cranky monk came to the door—even more irate than before!

Then we begged. One Dutch woman pleaded with the monk—almost kneeling to the ground—“We just want to pray.” I suppose the one thing Orthodox Christians had in common with, “other” Christians, was the deep and inexplicable yearning to pray to the same savior we believed, especially at holy sites. In some way it made us feel closer to our faith.

For a split second—and I mean only a split second—the monk’s heart melted. Finally, he obliged.

With one catch: “Yes Christians, No Arabs.”

As a student of religion, I knew that it was an absurd distinction. While most Arabs are Muslim, many Arabs are Christians and, in fact, many are Greek Orthodox, like the monk. That he wouldn’t let Arabs in was clearly unjust.

Several Arab teenagers had come up the mountain with us and I saw that they were crestfallen. My heart sank. We all stood there confused. Why? We’re all here for the same reason: to see the sacred cave. As Christians, we are supposed to welcome everyone to the house of the Lord, let alone any sacred place Jesus went. I wanted everyone who wanted to physically experience the place of the temptation —whether Christian, Arab or Jew—to see it too. I am Christian yet I had the opportunity to visit Mosques, Synagogues, shrines and holy sites for various religions. Its part of the religious understanding and appreciation I was aching for when I came into the religion class. So for this monk to reject these teens was utterly mortifying.

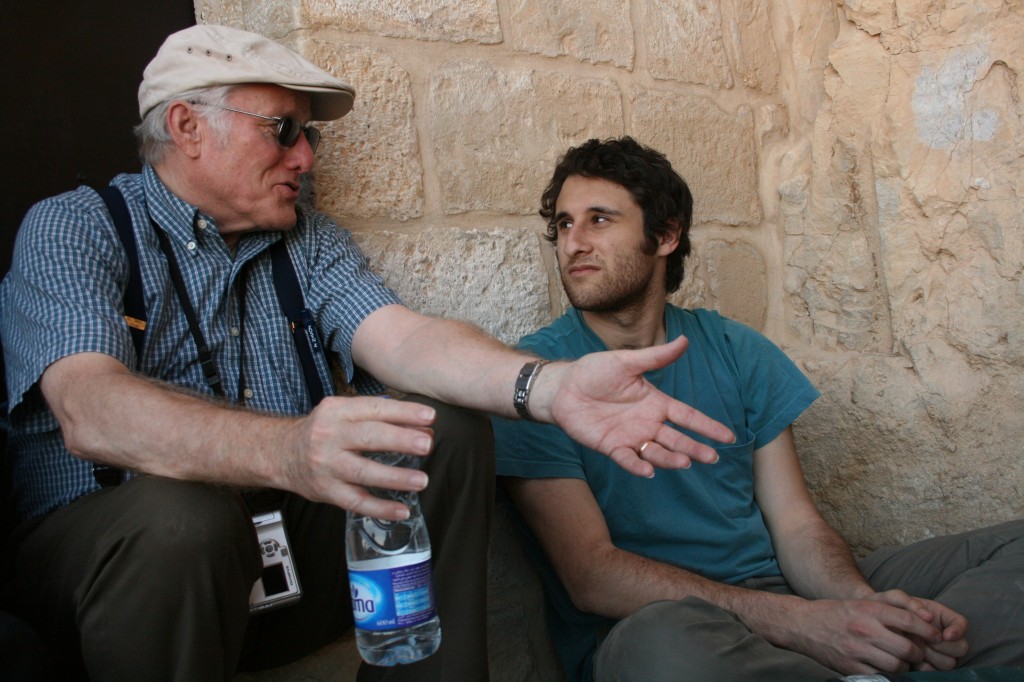

I was livid. As I stood in the entryway, part of me—the rebellious side of me— wanted to protest that if the Arabs could not go in, I would not either. I looked at Josh, begging him to be rebellious with me, but we both knew better. Was this really the time to barter with a power-hungry cranky monk after everything we had done just to get to the top of the mount?

I thought of the rickety old cable car.

The choice was difficult but clear.

A fleeting moment of guilt overcame me as the monk slammed the thick door with a bang in the faces of the Arab teenagers.

But I was able to put my guilty feelings on hold as I stepped into the cave. It was dimly lit with the flickering glow of candles. Gold, blue and red icons of Jesus decorated the compact, eerie space.

The cave in its natural and pure form brought to life another journey and a sacrifice Jesus made. The temptation of Jesus by the Devil became a part of his legend in Christianity. It was a far cry from mine. It being Lent, I was fasting from chocolate and sweets for 40 days and 40 nights—and was quite unsuccessful when it came to resisting Baklava. Yet Jesus ate no food, prayed in this tiny dark, damp cave for 40 days and 40 nights; defying Satan.

A sense of overwhelming gratitude fell over me. Not even my family, my friends or my relatives dead and alive were lucky enough to see this. Not even my mother who always taught us the Biblical versus surrounding the temptation of Jesus. None of them had been here.

Then I thought of my new friend Josh whom I was sharing the moment with —a Jew who was just as over-zealous as I to see Jericho and this cave. Then my mind turned to the Arab teenagers who had sacrificed their day and their aching legs. They trekked up the mountain with the same hopes that we had. The world is so divided, so bigoted, so broken, I thought. And I cried.