16

17

The J.J. School of Art was founded in

1857

and was proudly modelled on the

Royal Academy School in London. It was named after Sir Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy,

a businessman and philanthropist, who donated funds for its endowment.

While under colonial rule, the majority of the teachers at the school were

expats who taught along strict academic lines with no desire to explore

the avant-garde movements in Europe at the time. They sought to create

vocational artists for the purpose of the Empire, artists who would reproduce

nature and the environment as faithfully as possible. As they described “

our

native students have much subtlety of the eye and finger and will probably make

excellent copyists, engravers and mechanical draughtsmen. Perspective seems to

puzzle them.

”

7

Painting from the nude was only permitted in the diploma class

as at the school ‘

nudity, particularly female, was wrapped up in sin and Victorian

inhibition

’. Instead, Newton was taught such things as the fundamentals of

anatomy from an M.D at J.J Hospital. Newton described a college trip in

1940

that reflected the restrictive nature of the school’s teachings at the time:

“

Mr Sirgaonkar took the class to Trombay. He was the art master of the

elementary and intermediate classes at the JJ school of Art, Bombay. It was

1940

and I was

16

years old and learning to paint from scratch in the elementary class.

We had to do geometrical designs, draw still lifes of arranged objects with graded

pencils ranging from HB to

6

B, do memory drawing, lettering and paint and

trees and flowers in watercolours straight from the plants which the gardener

would cut from the campus garden and place in bottles on our desks.

The trip to Trombay was a rare treat. Mr Sirgaonkar did not have much

opportunity in class to show us what he could do, how he himself painted. In class

he merely supervised our work. But at Trombay he unravelled a mat and opened

his watercolour kit. He pinned a sheet of drawing paper to the board, and asked

one of us to fetch some water in a jar from a watering hole nearby. The array of

watercolour cakes of pigment gleamed in the sun.

Mr Sirgaonkar dipped a fat sable brush in water and worked it on to a cake of

chrome yellow until the brush was loaded with the colour. He then held the board

almost vertically and spread the yellow over the paper more or less evenly. I will

never forget his remark. He said “I paint the whole paper with a yellow wash

first, to indicate a sunny day?” He then mixed in greens and browns, painting the

nearby trees and bushes, and the same houses in the distance. The painting was in

confluent colours, with colours merging with each other. The effect was that of

19

th

Century British watercolours.

”

8

Unwilling to be confined in this manner, Newton continued his rebellion

against authority, establishment and convention. It was not long before people

outside of the J.J. School of Art started noticing Newton for the wrong

reasons, as J. Mohan writes

“

he was not only brilliantly talented with the pencil and charcoal but “he had the

gift of the gab - he loaded his talk, always spoken in a low voice, with punches

and expletives. What is more he could write as well as he could paint. Pen and

paintbrush were one and the same for him – to be used as a barbed lance not at

windmills but as his enemies.

”

9

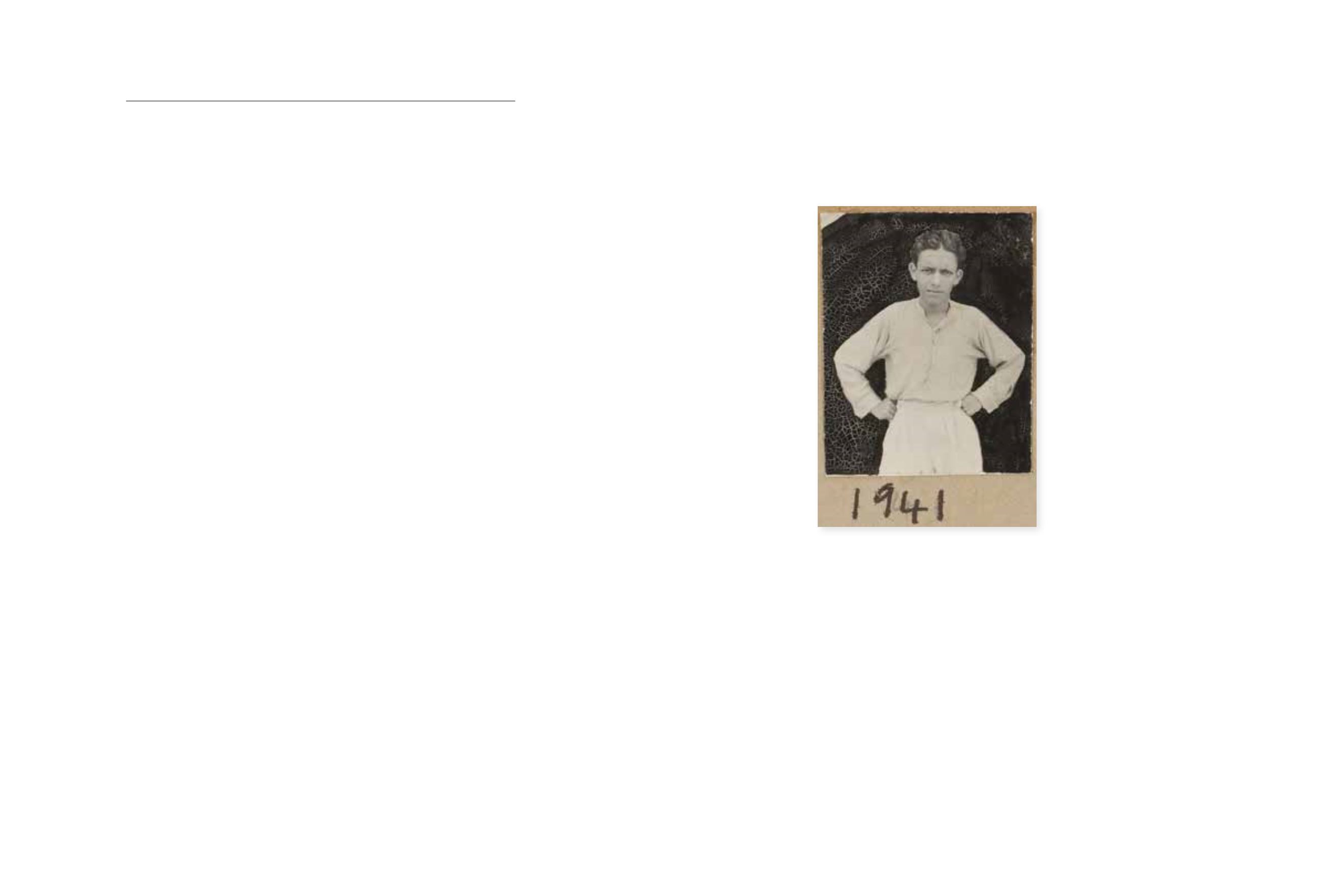

ART SCHOOL

1940—1945

Newton, aged

17

,

1941

© The Estate of Francis Newton Souza

He was not only brilliantly talented with

the pencil and charcoal but he had the gift of

the gab - he loaded his talk, always spoken

in a low voice, with punches and expletives.

—

J. Mohan