62

portal,andhe starts screaming inSpanish,I’m screaming in

English,and someoneelse is screaming inCholMaya,and

finally the rest of our party comes around.”Šprajcwalked

backward through theportal,says Jones,turned to face the

stonemonster’smaw,and calmly smiled.

“I had a few rum andCokes later,”Šprajc admits.

Watermayhavemade thedifferencebetween thesurvival

ofsites likeCobaand thedeclineofCalakmul.Cobaand the

cities in thenorthernYucatán,includingChichénItzá,were

still thrivingwhen those in the south—Chactún,Lagunita,

Calakmul—were abandoned.Many archaeologists now

believea longdrought throughout theYucatánmayhave led

to famine,warfare,and thebreakdownof the feudal system,

sparking a200-year collapsebeginning in the9th century.

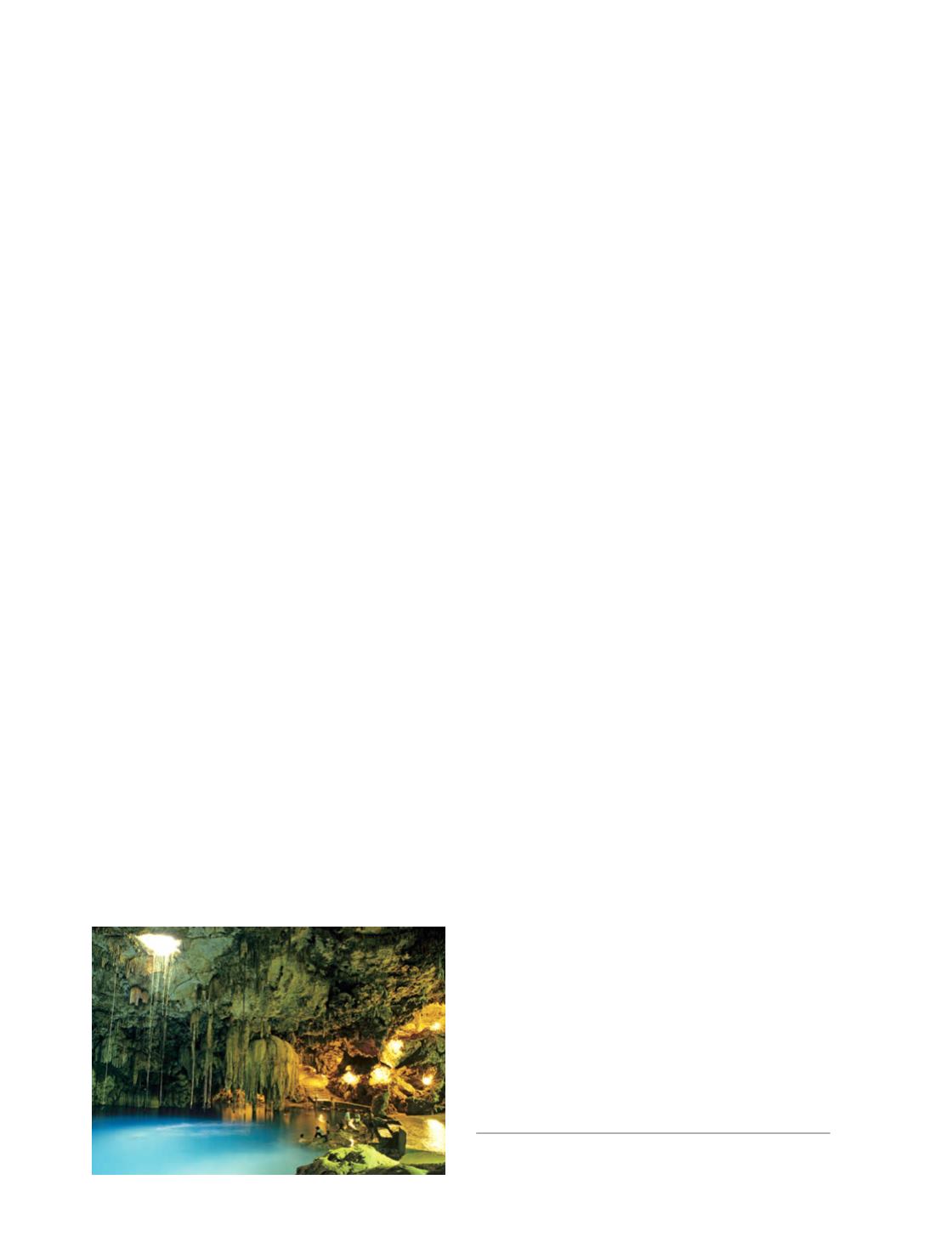

But thenorth isnecklaced incenotes,natural sinkholes

in the Yucatán’s porous limestone created by the same

Mesozoic meteorite that doomed the dinosaurs. The

impact exposed underground rivers through a series of

perforations, but it did not reach the southernYucatán,

which largely lacks cenotes.Near Tulum, rental cars in

front of us turn left intoGranCenote,disgorging swim-

mers eager to cool off after crawling up NohochMul.

Cold and clear, the aquamarine freshwater recedes into

a dark cave, one of the vital reservoirs that was perhaps

responsible for the survival ofMaya civilization in the

northuntil theSpanish conquest of the late17th century.

North, south, or neighboring,Maya sites remained

separate,more like the city states of ancientGreece than

the empireofRome.“Theywerenot united ever,”explains

Šprajc,ashedrivesme to the coastal areaof Tulum.“They

probably didn’t even feel like they belonged to the same

nation.They had a lot of trade networks.But that doesn’t

meanwe are all friends.We have war, but trade goes on,

just likenow.”

Tulum servedCoba as its port on a vital trade network

that extended as far as Honduras. In early drawings by

Catherwood,Tulum featured vegetation growing from

atop themain

castillo

and trees sprouting from pavilions,

much like the jungle-shrouded ruins of the southern

Yucatán today. Now reconstructed, Tulum’s tropical-

paradise-meets-archaeological-site attracts visitors who

stream inwithbeach towels,oblivious to the lean scientist

“Becauseof theblack

market, Šprajc often

destroys his paths.”

among themwhooncemapped theastronomical alignment

of these buildings.

Šprajcpointsoutastructuredevoted to theplanetVenus

and another withmonster figures carved into the corners.

Artistic but practical, theMaya often buried their dead

under theirhouses,withofferingsofpottery,jade,andother

treasures.When they expanded, they did so directly atop

existing buildings.Houses turned intomansions turned

intopalaces in this recyclingpractice,which sealedoff one

age after another,entombing treasures nested likeRussian

dolls and vulnerable, today, to raiders who often display a

sophisticatedunderstandingofMayapracticesby tunneling

withinbuildings.“They sawedoff thecarved surfaces,”says

Šprajc.“It’s limestone, so they could cut it. If they couldn’t

take thewholemonument, theywould carve it off.”

Though looting and the sale of antiquities is illegal, a

blackmarketpersists,which iswhyŠprajcoftendestroys the

paths tonewlydiscovered sites.He’sbeenknown toprovide

falseGPScoordinates to journalists.Accurate information

published in scientific journals is usedby other archaeolo-

gists,who return to excavate,with luck finding the jade

masks and polychrome pottery before thieves do. “First, I

rescue the information,”explainsŠprajc in themost impas-

sionedpitchhiseven tenorallows.“Then,oncewepublish,if

they steal it later theycannotat leastpublicly sell it,because

wewill knowwhere it came from.”

There’sno jungletoshroudpotentialplunderersatTulum,

where iguanas sun themselves atopoff-limits temples.The

dutiful stop to readplaques about thedecoratedTempleof

the Frescoes, butmostmake for the clifftop stairway that

takes them40 feetdown to thebeach.“Museumsnowhave

to competewithDisneyland,”Šprajc says. “As long as it’s

authentic,exposure is good.”

His personal tolerance for beaches is limited.Emerging

from the jungleafteranexpedition,Šprajc seeks“agoodbar

andagoodrestaurant,andyouswima littlebitbut then,OK,

let’s goback.”But nowhehas abus to catch andmoney to

raise. “I’m 60 years old in a few days. I will probably have

only thenext few years if Iwant todo some tough jobs.”

Amonth later, I hear from Šprajc. Backing secured,

he’s planning another reconmission in the biosphere in

March.Asmuch as he trustsme with his story, he won’t

saypreciselywhere.

ElaineGlusac

writesregularly for

TheNewYorkTimes

.Like

Indiana Jones, she hates snakes.

Swimmers at

Gran Cenote

WILLIAM SCHILDGE/GETTY IMAGES