In the first half of the year, Fundamental Value struggled, giving up years worth of outperformance in two quarters. In the third quarter, FV outperformed slightly, but not nearly enough to claw back its losses. FV is down -11.8% net of fees in 2020, compared to a gain of 5.5% for the S&P 500. Since inception, FV has returned 12.3% annualized vs 13.5% for the S&P 500.1

Our performance this year has been very distressing. However, it has not been demoralizing, for there is a silver lining: we believe that the prospects have never been better for value investors than they are today. Read much more below.

Programming note: The second and third quarters of 2020 were unprecedented in many ways. We have a lot to say, much of which will be controversial. We felt it was imperative we fleshed out our thoughts as completely as possible. Therefore, we’ve combined our second and third quarter commentaries into one longer piece rather than write two shorter pieces mid-quarter as usual. This is Part I. Please look out for Part II shortly.

Part I: Birth of a Bubble

Prior to 2020, we watched in surprise as growth stocks soared despite already elevated valuations. Over the course of 2020, we watched in disbelief as those valuations reached completely untenable heights. Sitting here at the end of third quarter, we now have no qualms calling a duck a duck: we’re in a tech bubble.

In Part I, we’ll talk about the birth of the bubble. How did we get our second tech bubble in just two decades? What makes story stocks so irresistible? What are the signs of speculative frenzy?

In Part II, we’ll talk about the anatomy of the bubble. We’ll take a look at our portfolio as a whole, as well as some individual stocks: some value names that are dirt cheap, and some growth names that are outrageously expensive.

Value has underperformed growth for a decade-plus, and 2020 is the worst year on record for value in nearly a century of data. Despite this underperformance -- in fact, because of this underperformance -- we think value is poised for historic relative returns. We are convinced that today is the day to go all-in on value. By the end of this piece, we hope to have convinced you too.

The pandemic and value investing.

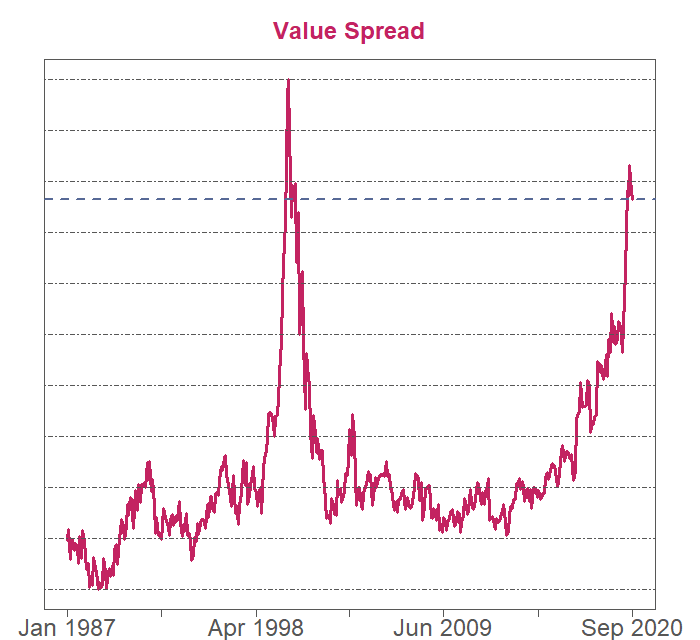

Over the past few years, we have written ad nauseum about the underperformance of value stocks over the past decade-plus, and the pain this has caused for us and other value investors. Our calculation of the “value spread” -- the difference in valuation between the cheapest and most expensive stocks in the market -- has been elevated for quite some time.

There were several narratives purporting to justify the abnormally large value spread, purporting to explain why “this time is different.” Perhaps growth stocks deserved their new, larger premium because growth companies are of much higher quality than they were in the past. Or perhaps the decline in interest rates explained the premium. We did not think the data supported these narratives. We did not think this time was different.2 Instead, we believed that the abnormally large value spread meant the same thing then that it had always meant: that the future relative returns to value were likely to be exceptional. Value investors would finally be rewarded for sticking with their discipline after a decade of pain.

Our hopes were high that the trend favoring growth would reverse in 2020. We predicted that in a pullback, the market would place appropriate emphasis on companies with proven cash flows, rather than continuing to swoon over the unproven ambitions and extravagant promises of glamorous growth names.

Then the pandemic hit.

The pandemic hurt many value stocks. Value stocks tend to operate in the physical world, in staid industries such as real estate, travel, and hospitality. Many of these industries have been decimated by the COVID-19 fallout.

On the other hand, the pandemic didn’t merely spare growth stocks -- many have benefited handsomely. Growth stocks tend to operate in the digital world, in growing industries such as cloud computing and subscription software. They often compete with real-world businesses: Amazon with retail stores, Peloton with gyms, and Netflix with movie theatres. The pandemic shut down these physical competitors, dramatically pulling forward adoption of digital goods and services.

It would have been difficult to invent a scenario better engineered to exacerbate the already-elevated value spread than the pandemic. It was, in essence, a historical accident, a fluke of epic proportions, that seemed to validate all the unrealistic assumptions surrounding growth’s decade-long ascendance.

In 2020, the Russell 1000 Pure Value Index has underperformed the Pure Growth Index by a shocking 85% through September. According to the canonical Fama-French value factor, 2020 is poised to be the worst year on record for value -- and their data extends nearly a full century, all the way back to 1926. Below is an update to the value spread chart from our 2Q19 letter.

The value spread has been higher… but only in February, March and April of 2000. It is now higher -- much higher -- than in every other month in history.

Do you think we were in the midst of a bubble in January of 2000? We certainly do. Do you think you should have bought growth stocks then? We certainly do not.

In the five years after January of 2000, the Russell 1000 Pure Growth Index declined by more than half. The Pure Value Index more than doubled. An investment in the latter would’ve left you with 4.5 times as much money as an investment in the former.

The logical and disastrous extreme.

If any trend goes on long enough in the financial markets, it begins to garner an air of inevitability. Few can remember the trend’s beginning, and even fewer can imagine its end.

The trend becomes self-reinforcing. Rising expectations beget new investors, new investors beget higher valuations, and higher valuations beget rising expectations.

However, this positive feedback loop cannot continue ad infinitum. Eventually, expectations become wildly unrealistic. Eventually, there are no new investors to be found. Eventually, companies must earn profits to justify their ever-increasing valuations. When it becomes apparent that this will not happen, a trend collapses under its own weight.

Before March of 2020, growth’s long outperformance had led to extreme valuations and extreme expectations. There seemed to be an implicit consensus that in order to invest successfully, it was sufficient to invest in the hottest companies; it was sufficient to invest in the coolest tech, the companies making the biggest promises, the companies in the trendiest industries -- and the price you paid didn’t matter.

The pandemic reinforced that notion. When the pandemic struck, the case for owning value -- its near-term earnings power -- disappeared overnight. Why bother to own old-economy, low-growth businesses if they aren’t even making money today? The hunt for growth at the right price became a frenzy for growth at any price. We are now reaching the logical and disastrous extreme of that narrative.

“Price matters” should not need to be said, but today, unfortunately, it does. This is not the first time this lesson will be taught by the financial markets. Ask those who got caught speculating in any recent bubble: marijuana in 2019, cryptocurrency in 2018, financials in 2007, or telecoms in 2000.

An example will help illustrate.

Consider Cisco Systems. In 1999, Cisco earned $2.1b in net income on $12.2b in revenue. Since then, Cisco has more than quintupled income. Over the last twelve months, Cisco earned $11.2b on $49.3b in revenue. This is an unqualified success by any metric… except investment returns. An investor who bought Cisco at the top in March of 2000 would still be deep in the red today, over two decades later. They would have lost more than a third of their money investing in Cisco for two decades despite Cisco’s enormous business success.

Interest rates are low today. Many investors use that to justify nosebleed valuations for growth names. But no matter how low of a discount rate you use, Tesla has to eventually earn $400 billion and return that capital to shareholders, or investors will lose money from today’s prices. Zoom has to eventually earn and return $150 billion. Snowflake has to eventually earn and return $70 billion.

Any of that is possible. But it must be emphasized that these companies could be wildly successful, and, like Cisco, grow revenue and earnings for decades, but still not come anywhere close to justifying their valuations. Cisco earned $2.1b in 1999; Tesla, Zoom and Snowflake combined have earned $250m over the last twelve months. Cisco had a peak market cap of $550 billion; Tesla, Zoom and Snowflake have a market cap over $600 billion.

We often hear that the value spread is justified because new-economy companies are vastly superior to their old-economy counterparts. These new digital businesses are asset-light, high-margin, recurring-revenue businesses. Yes, some growth stocks today are wonderful businesses -- much better businesses than any value stocks. But this line of thinking elides the distinction between a wonderful business and a wonderful investment.

Warren Buffett has said, “It's far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.” But is it better to buy a wonderful company at an egregious price?

Consider Cisco again. In the five years after March of 2000, Cisco more than doubled earnings… but it’s stock price was down 77%. On the other hand, consider Republic Services, a fellow S&P 500 component, but in the waste disposal industry -- boring, old-economy, low-growth. This was a classic value investment opportunity at the top of the tech bubble, with Republic trading for just six times earnings in March of 2000. In the five succeeding years, Republic increased earnings by a pedestrian 15%, but its stock price more than tripled. An investment in Republic would’ve left you with 13.5 times as much money as an investment in Cisco.

The appeal of growth investing.

We have a lot of respect for smart growth investors. Growth investing is hard. A good growth investor must see far into the future with uncommon clarity. They must predict what new technologies will emerge, what new business models will prove successful, and what management teams will be able to execute. The companies they fund must disrupt an existing market or create a new one, and they must make enough profits in that market to justify the price they paid before the next great business comes along and disrupts them in turn.

But being a growth investor is very appealing. It is exciting and rewarding to invest in hot new technology and ideas. People with interesting business ideas will seek you out, and you’ll be a hit at dinner parties. Investing at an early stage in the right growth company can lead to life-changing wealth. And if an investment does go wrong, no one will blame you, because everyone agreed with you in the first place.

Contrast this with value investing. Value stocks trade cheaply relative to earnings or assets; by definition this means they are relatively unloved by the marketplace. Value investing means finding companies that others eschew, investigating the problems at these companies, and determining whether or not these issues are as serious as others think.

Consider some of our current value investment theses:

Ryman Hospitality runs some of the nation’s largest hotels and caters almost exclusively to large group events. That business has disappeared during the pandemic. We think that, some day, large in-person conferences will resume.

The recent history of Wells Fargo has been nothing but a series of PR disasters. We think that the scandals and fines are mostly behind them, and new management should be able to return Wells to a more typical bank profitability profile.

These are scary investments to make. They are not fun to talk about at cocktail parties. These companies are in the news for all the wrong reasons. Even if you’re right, you won’t become generationally wealthy -- you’re hoping for a solid return on your investment, but it’s not a lottery ticket. If you’re wrong, you’ll look like an idiot. Being a contrarian and being wrong could lose you your money, your job, and your investors.

We bring this up not for pity, but because this, we believe, is the fundamental reason for growth’s long-term

statistical underperformance: its emotional appeal. People prefer to be growth investors for reasons other than the financial return. Therefore, we should expect returns to growth capital to be lower.

If you’re investing in a potential lottery ticket growth stock, and the company is exciting and fun, and everyone else agrees, but you have no particular expertise in technology, and you have no special insight into the future of society,

you should be very concerned. Theoretically and empirically, that is likely to be a terrible investment strategy. Without an edge, you might as well be playing Powerball.

Unfortunately, indiscriminate gambling in the stock market has become something of a national pastime in 2020. This has resulted in

mind-boggling returns for the most richly valued and speculative securities: if you owned all 191 publicly-traded companies with a market cap over $1 billion and negative operating income in 2019, you’d be up 48% this year. The S&P 500 is up a measly 8.2%. It appears to us that investors in aggregate are not carefully analyzing these companies; instead, they are bidding up all lottery tickets in sight.

Consequently, growth stocks have become so expensive that their expected returns may be even worse than Powerball tickets. At least with a Powerball ticket, there is tremendous upside if you are lucky enough to win. On the other hand, consider Tesla. With a valuation of $400 billion, Tesla has the sixth-largest market cap of all US-listed public companies; it is already priced like it is one of the most successful companies in the history of the world.

Will Tesla eventually dominate worldwide transportation, like Facebook dominates social media, or like Google dominates online search, or like Amazon dominates online shopping and cloud computing? This is not a bet we’d like to make, but it is within the realm of possibility. However, it is not within the realm of possibility that Tesla

wildly exceeds these expectations. Tesla is already priced for historic success.

Therefore, Tesla is no longer a lottery ticket. Investors are bearing enormous downside risk if Tesla fails to dominate the transportation industry, and little upside if Tesla succeeds. We suggest those looking for an asymmetric payoff buy Powerball tickets instead.

The signs of speculative frenzy.

The signs of speculative frenzy are legion.

The most visible has been the dramatic expansion of retail trading. This echoes the retail stock fever of the late 1920s and the late 1990s. In the 1920s, retail mania manifested as stock tips from

shoeshine boys; today, stock tips come from

subreddits,

TikTok influencers, and even a

boorish sports writer who contends without irony that he is a better investor than Warren Buffett. In the 1990s, retail mania manifested as people

quitting their day jobs to day trade stocks; today, millions of young new retail investors use gamified apps like Robinhood to day trade stocks and, even more worryingly, complex and highly leveraged derivatives.

Some commentators see the rise of Robinhood and its ilk as the democratization of investing. This is misleading. Index funds have already democratized investing by providing retail investors cheap access to the long-term appreciation of equities.

Roboadvisors further improved upon this idea by providing simple, automated and personalized investment plans to anyone with even a little money to invest. These are genuine financial innovations that have made retail investors better off.

Robinhood, on the other hand, provides little if any incremental value. It has merely taken an already over-gamified stock market and turned it up to eleven, encouraging

marginally informed speculation, overtrading and the use of complex derivatives that will almost certainly result in subpar investment returns over time for the vast majority of its users.

Robinhood is creating traders, not investors. There is a naive, pervasive, and pernicious myth that anyone can make money as a stock trader. Relative performance is infamously a zero-sum game: outperformance for one trader must be underperformance for another. And trading is not a level playing field. Professional traders are smart, hard-working, and highly informed, and they spend a lifetime studying markets. Nonetheless, most of them will

underperform the market.

Bloomberg’s Matt Levine put it best when he

said, “Active investing is a bet that you understand the market better than everybody else does, and if you started investing a month ago and limit your research to looking at the trending stocks list on an app, you will lose that bet.” Retail traders can hope to get lucky in the short term, but most have no hope of outperforming in the long term. Pretending otherwise is intellectually dishonest and a disservice to the public. Retail investors, in our opinion, are best served by buying and holding cheap, diversified funds, rather than trading individual stocks and options.

The long outperformance of growth, especially given its concentration in consumer-facing tech companies, has spread the myth that in order to get rich, all you need to do is buy shares of the companies that make your favorite products. Maybe you own a Tesla, spend all day working on Slack and Zoom, do most of your shopping on Amazon, have an iPhone, and watch Netflix. You look at the stock charts and see that you would’ve more than tripled your money this year if you had owned shares of these six companies. Who can resist such easy money? As Benjamin Graham

said about the bubble preceding the Great Crash of 1929, “Countless people asked themselves, ‘Why work for a living when a fortune can be made in Wall Street without working?’”

This effect has been compounded by the pandemic. In other eras, people had to quit their day jobs to trade stocks. Sadly, today many are already without jobs and view trading as their

only path to wealth. For others, without access to friends and family, without restaurants and bars, without work and vacation, without sports and sports betting, speculation in the unusually volatile stock market has been a welcome if misguided source of entertainment.

An obsession with trading has swept through the country like a virus. The obsession is viral in both senses of the word: rapidly circulating, and highly dangerous. Tragically, one 20 year-old Robinhood trader

committed suicide after some complex options bets he didn’t fully understand went awry. We desperately hope that no more novice investors will lose their lives. But many more will lose their money.

Brokerage firms are reporting astonishing user growth. As the Wall Street Journal says, “

Everyone’s a Day Trader Now.” Robinhood alone added three million new accounts in the first quarter,

50% of whom are first-time investors. E*TRADE saw more users open accounts in the month of March than in any full year on record. In the second quarter, TD Ameritrade saw customers

more than quadruple their trading activity year-over-year.

Other late-stage behavior is rampant; the bubble has led to some truly bizarre speculative frenzies.

-

Retail traders seem to have found speculation on high-volatility stocks insufficiently stimulating, and have taken to buying call options in huge numbers. Small investors bought call options on $500 billion of stock in August, five times the previous monthly high. Options volume exceeded share volume for the first time in history. The most popular options typically expire in weeks or months, yet more than 20% of S&P 500 options traded in the second quarter expired in less than a day, up from 5% previously. Tesla calls were more expensive than Tesla puts, an extremely rare phenomenon; investors were more worried about missing out on opportunities to make money than they were about losing money. Expect to see heightened volatility in the future as these enormous options purchases have created short gamma positions at options dealers; dealers will be forced to dynamically hedge their positions in procyclical ways, buying when the market is up and selling when it is down.

-

Derivatives madness is not confined to retail traders. While SoftBank was never exactly a paragon of moderation with its oversized bets on overhyped late-stage startups, it has dramatically upped the ante recently. In early September, SoftBank was outed as the mysterious “Nasdaq whale” who had single-handedly exacerbated the melt-up in technology shares in August by purchasing call options on an astounding $30 billion of individual stocks.

-

For about a week in early June, a slew bankrupt companies like Hertz, JCPenney, and Whiting Petroleum soared. Robinhood users bought these stocks hand over fist. Experts and bond traders were confounded as there was no plausible path to a significant recovery in bankruptcy for equity holders. Hertz tried to sell $500 million of nearly worthless stock into this mini-bubble. The SEC stopped them, thankfully, as the bubble popped shortly thereafter. After quintupling in less than a week, Chesapeake Energy proceeded to lose 93% of its value by the end of the month.

-

The market’s embrace of the recent stock splits in tech darlings Tesla and Apple is eerily reminiscent of the stock split fever that accompanied the final advances of the late 1990s.

-

Blank-check companies called SPACs have raised over $57 billion this year. This is almost five times as much as in 2019 -- in fact, it’s more than the total amount raised by SPACs prior to 2020. These empty shells sit on an exchange until they find a private operating company to merge with. This enables the target company to go public without the typical scrutiny of an IPO. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with any particular SPAC, but the excessive demand and issuance in 2020 is a symptom of the ubiquitous urge to blindly speculate: investors buy into a SPAC without even knowing what the eventual target company will be. We will have much more to say on specific SPACs and SPACs in general in Part II.

We see evidence of “analysts” abdicating responsibility of doing any analysis whatsoever. Quotes like the following are more and more

common:

Alicia Levine, chief strategist at BNY Mellon Investment Management, said she’s telling clients to stay in the stock market amid stimulus measures from the Federal Reserve and U.S. government.

“That is still our message,” Levine said in an interview on Bloomberg TV and Radio. “It’s extraordinary. I think we’re all scratching our heads, but the market is telling me you’ve got to be in it.”

This reminds us of Chuck Prince’s infamous

quote from 2007, just before the Great Financial Crisis:

“When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will be complicated,” Prince said. “But as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.”

These are quotes from people who are happy to be wrong as long as they are doing it with the crowd, people who are driven by the fear of missing out rather than by sober analysis.

That’s not something we can abide by. It has been excruciatingly painful, both financially and psychologically, to be on the sidelines during this period of euphoria. However, we believe in our analysis. We believe that history will look back on this period as one of

irrational exuberance. We believe that value investing will yet again prove its worth. And we believe that we are positioning our clients for the best long-term outcome, despite the interim pain.

The anatomy of a bubble.

In Part II, we peer inside the bubble.

We’re in a barbell market: there are lots of very expensive stocks, and lots of very cheap stocks. That creates opportunities for discerning investors. We’ll share what we’ve found.

We’ll take a look at expensive growth stocks. At the top are the kings of the bubble, the five tech megacaps: expensive valuations, but phenomenal companies. Their size, quality, and relatively reasonable valuations obfuscates the true extent of the bubble behind them.

Next are the contenders to the throne: nosebleed valuations, but potentially transformative tech. And behind them are the mere pretenders: the copycats who bring nothing to the table but their ability to sell a good story into a credulous market. Among the contenders and the pretenders, investors search for the next Apple or Amazon, and mania is at its height.

We’ll also take a look at cheap value stocks -- ignored, unloved and beaten-down -- where investors can find great deals even in the midst of a bubble. Investors have been so focused on chasing the momentum of growth stocks that they’ve missed opportunities to own solid but temporarily troubled companies at discounted prices. They might not be the best

businesses, but in our opinion, they are the best

investments.

- Bireme Capital

Follow our content by subscribing here.

1 Net calculations assume a 1.75% management fee. Fee structures and returns vary between clients. FV inception was 6/6/2016.

2 Rather than relitigate these issues, we’d point you to our previous work, as well as the exhaustive takedowns of other practitioners. Here we’re going to focus more on the history and psychology of the bubble.