Follow us on Twitter: Follow @IdarMethod Last updated: April 30, 2018

I am in favor of agile. But due to some mistakes in present-day agile practices, I have a custom baseball cap that says, “Agile... just say NO!”. Surprisingly, most developers respond positively to this cap, despite the popularity of agile.

What’s wrong with agile? I believe that the basic idea behind agile is sound, but the way it’s being practiced nowadays often does more harm than good. Here are the mistakes being made, and the harm they cause:

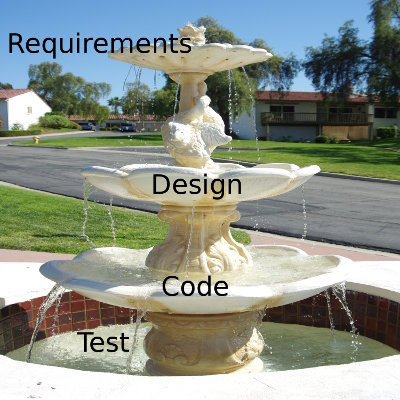

Aside from the foolish daily meetings which should be dropped, agile’s root problem is that it has over-reacted against the waterfall process. The waterfall process rigidly steps the entire project through the stages of specifying requirements, creating the design, writing the code, and testing and releasing. But this inflexible approach fails because the human mind is unable to think of everything in advance. Beyond a certain size, the human mind can’t create a large requirements document because the mind can’t think of all the details. Likewise, it can’t create a monolithic design because details will be overlooked. The solution is to do what good software managers have been doing for decades — divide and conquer:

Each empty piece in the overall design is a subsystem or sub-subsystem, and it should be small enough that a few developers can comprehend its complete requirements and design. They will need to fill in the details of the requirements, and they should work with marketing or the customer while doing this. The design should be small enough to not be overwhelming. The code should be no more than around 10K lines. During this process, the developers (and customer) will discover some changes they want to make to the requirements and/or design of the piece. But these can be accommodated because the changes will not be extensive, and the piece of software they are creating is small enough that the developer’s minds can visualize the needed changes, which they can make in a few days.

Management will have several of these fountains running concurrently, depending on the number of developers on the project. These fountains will be in different phases; there is no reason to keep them in sync (as one does with sprints). Fountains will have differing lengths (times) as well, since some pieces of software will take longer than others. In fact, fountains need not be scheduled at all because it’s not possible to accurately schedule tasks, as pointed out above. (However, it’s possible to schedule the entire project because the mean time of tasks can be estimated.)

If some fountains are not finished when it’s time to release a build, then they will not be in that build. When one fountain finishes, its developers will be put on another fountain. The first fountains will be the essential features of the software, creating a working skeleton. Then, fountains will implement features in the order that their requirements become stable, or in order of importance, putting the “want”-features later in the project.

This fountains approach qualifies as agile because details of requirements and design are decided later, in smaller chunks, instead of up front when people can’t think of all of those details because their quantity is overwhelming. Yet, this approach also minimizes rework because requirements and design are done thoroughly before implementation. Because of its high efficiency, the fountains process causes the team to provide maximum throughput, giving the project the greatest possible chance of meeting deadlines. Managers can watch the progress of implementation of the importance-ranked features, and can use this data to estimate what features will be ready when the deadline occurs, and can take any corrective action well ahead of the deadline.

There is another subtle reason why the fountains approach boosts efficiency compared to the waterfall approach. When marketing is involved, and especially when contracting, there is often a separate team creating requirements. With the fountains approach, the requirements-team will work in parallel with the developers and testers, instead of sequentially. The project-wide effect is that time spent creating requirements overlaps most of the development-time, thus adding little time to the schedule due to writing requirements.

In summary, the fountains process combines the advantages of agile with the advantages of waterfall by breaking the project into pieces, each of which can be implemented with a fountain.

A perspective: Long ago, one of my managers said, “In programming, old ideas keep being recycled under new names.” Agile and fountains are two of them, because competent software managers having been running their projects this way for decades. Back then, they didn’t call it “agile” or “fountains”; they called it “sensible management”. Any sensible software manager knows that a large software project must first be specified and designed at a system-wide level that lacks detail, and then the team will spend most of its time filling-in this hollow project. They start with what can be implemented now, but with an early goal of getting a skeleton system running. Then the team will spend most of the time implementing the rest, hopefully with enough time at the end to polish the software up to excellent quality. This has been going on for decades, and agile is merely an attempt to systematize that good management.