Life on the margins in the West Bank

BETHLEHEM — On Thursday, the fifth day of our journey, we heard from three separate communities in the occupied West Bank about their engagement with the land. In the morning, we visited Deheisha, a Palestinian refugee camp to the south of Bethlehem. Then, after lunch, we travelled to the nearby Jewish settlement of Alon Shvut, where we spoke with a professor of the Har Etzion Yeshiva. And finally, in the evening, we went to the unrecognized Bedouin village of Susya.

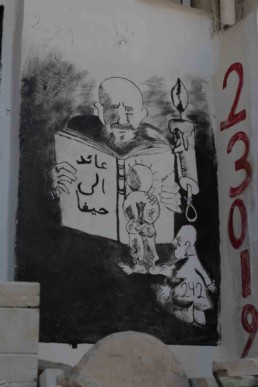

We woke up in the Palestinian homes where we spent the night and then regrouped and traveled to Deheisha. Omar Hmidat, the son of the local imam, came to greet us and be our tour guide. Hmidat, 26, is majoring in media studies at Al-Quds University as part of the Bard College honors program. His thesis is on “the visual narratives of Palestinian political expression” – something that was evident from his in-depth knowledge of the murals that dotted the encampment.

The camp itself was created in the aftermath of the Arab-Israeli War when, in 1949, refugees from Hebron and 45 villages west of Jerusalem sought temporary asylum. According to official statistics from 2015/16, there are as many as 15,000 people living on an area of one square kilometer. Over the years, however, the population has expanded rapidly and as many as 22,000 people now live immediately outside the camp, Hmidat said.

Though the camp is largely comprised of permanent structures, the UNRWA is still operative in the area.

While the community is less reliant on the UNWRA for aid than it once was, Hmidat explained to us that its presence is also symbolic. It is, he said, “proof of the right of return” for Palestinians.

The meaning of “right to return,” he continued, has evolved from the refugees’ right to resettlement in their former homes to a broader understanding of access and basic civil liberties. Deheisha is located between Zone A, governed by the Palestinian authority, and Zone B, which is under joint Israeli-Palestinian security control.

After touring the refugee camp with Hmidat, we went to his home where we met his father, Sheikh Ibrahim Hmidat. He took time to explain to us that life was hard and dispiriting for the residents of Daheisha, but that Islam has helped to sustain the community, giving it hope for the future.

After lunch, we met with Rabbi Yair Kahn at Har Ezion Yeshiva, in the settlement of Alon Shvut. A student of two luminaries of the Modern Orthodox movement, Joseph Soloveitchik and Aaron Lichtenstein, Kahn serves as the editor of the yeshiva’s virtual Bet Midrash Talmud series.

The rabbi opened the conversation by saying, “To be Jewish is to be part of a nation.”

Through references to the books of Esther and Ruth, it quickly became apparent that Kahn derived his authority from religious texts, and not international agreements and treaties. Where the people of Deheisha spoke in terms of checkpoints, economic self-determination, and water rights, Kahn repeated time and again about “providence” and “the hand of God” in guiding Jewish settlement of the West Bank.

Alon Shvut is a settlement in Zone C, administered by the Israeli military, but is considered part of what would be the future state of Palestine. As such, most of the international community considers its existence illegal under international law, a claim disputed by Israeli government officials who cite the existence of a Jewish community there before 1948.

Although the rabbi was reluctant to speak personally to issues of politics or theology, he stressed the importance of tolerance and, to some extent, pluralism, at the yeshiva.

“What we are taught here is complexity – that there are different opinions,” he said, “and that you must respect them even if you disagree with them.”

After leaving the yeshiva, we were joined by a rabbi of the more progressive Reform movement of Judaism, Rabbi Arik Ascherman.

Ascherman, the former president of an organization called Rabbis for Human Rights, now heads an organization called Torah of Justice. He led us to a Bedouin encampment at a West Bank community called Susya.

The Bedouins at Susya were uprooted from their community in 1986 when an ancient synagogue was discovered on their land and expropriated by Israel. Since then, a legal battle has ensued over rights of ownership and settlement. Before the election of Donald Trump in the United States, Ascherman explained, the Israeli authorities had made accommodations and allowed the Bedouins to build on their farms, but over the past year these talks have fallen apart. We had to chance to meet some of the families affected by the dispute, and they informed us, with Ascherman translating, that the Israeli army had dismantled their makeshift homes seven times in recent years. This encounter demonstrated the determination of displaced families to stay on their land, but also the precarious existence of Palestinians living in Zone C, where Israeli civil and security control is an everyday reality marked by checkpoints, outposts and growing settlements.

Speaking to the sectarian nature of the conflict and why he does this work, Ascherman reminded us of the need to exercise individual acts of kindness to chip away at harmful stereotypes between different peoples.

“I will do it again and again,” explained Ascherman, recounting an occasion when he was beat and arrested by the Israeli Defense Forces, “for a young boy to say, ‘A tall Jewish man in a kippah came to my rescue and told me not to be afraid,’ because if there’s any hope for any of us, it is that [Palestine’s] children are mine, too.”

Photos from day 5:

Family man, not elves, behind Christmas treasures in Bethlehem

BEIT SAHOUR — Pilgrims and tourists buy souvenirs to remember their visit to the Holy Land, but for Ghassan Qumsieh, the trinkets are his form of survival.

Qumsieh, born in Palestine, got up from the dinner table eager to show his family’s guests – us, two Americans, and our teacher, Professor Haroon Moghul – his creation.

“One minute, one minute,” he said in English slowly. Qumsieh walked across the kitchen and retrieved a miniature nativity scene from a shelf. He placed it near our dinner plates, which were now cleaned after a few helpings of makloubeh, a dish of rice with cauliflower and potatoes, served with chicken and a side of yogurt.

Qumsieh, an Orthodox Catholic, takes pride in his craft. He proudly presented one of his nativity pieces – complete with baby Jesus and wise men figurines. Using various motions like a game of Charades, and the English he knows, he explained how he carefully cut the pieces and glued them together to create tourist treasures. He twisted the star at the top of the wooden barn site and a slow melody began to play.

Qumsieh’s days begin early and end late. After an 11-hour workday at his shop, he will sometimes come home, take a quick nap, and work on various trinkets until 1 a.m. This time of the year, with Easter approaching, the job is more arduous, as more tourists and pilgrims visit Bethlehem. But more business, more money.

“Life here is very expensive,” he told us.

His earnings support the home he bought about a decade ago – a modest but cozy three-bedroom fifth-floor unit in Beit Sahour, a little town outside of Bethlehem. The living room is adorned with Christian memorabilia, like a larger-than-life rosary tucked behind a family photo, an assortment of plants, and a picture of Jesus. The coffee table is lined with charms from his workshop, packaged and ready for the Easter crowds. On the kitchen counter sits a large box of wooden crosses and accessories yet to be glued together. “I’m very happy here,” he tells us.

It wasn’t an easy journey. Qumsieh was forced to leave the country for Jordan after the Six-Day War in 1967. He worked day and night at a minimart to start a new life only to repeat the process after his father died and he returned to the West Bank.

But his tenacity has paid off, a fact that’s apparent by interacting with his daughters – two confident and ambitious teens, who served both as hosts and, after Professor Moghul departed, our translators for the rest of evening when their parents’ English failed. Siwar is a boisterous and confident 14-year-old, who enjoys cooking – a skill she learned from watching “Top Chef” on television. “I want to be a chef,” she says, briefly glancing up from her cell phone. Her older sister, Nadine, 18, graduates this year from high school. Thanks to the hard work by Qumsieh and his wife, Rula, a history teacher, Nadine will go on to college, where she plans to study hotel management.

His fatherly instincts transferred over to his houseguests, too. “You’re my daughters, too,” he told us. When we left the next morning, he gifted us each with two of his Christian ornaments. As he plucked them in our hands, he smiled and said, “So you will remember me.”