Life on the margins in the West Bank

BETHLEHEM — On Thursday, the fifth day of our journey, we heard from three separate communities in the occupied West Bank about their engagement with the land. In the morning, we visited Deheisha, a Palestinian refugee camp to the south of Bethlehem. Then, after lunch, we travelled to the nearby Jewish settlement of Alon Shvut, where we spoke with a professor of the Har Etzion Yeshiva. And finally, in the evening, we went to the unrecognized Bedouin village of Susya.

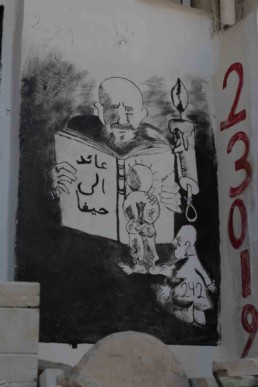

We woke up in the Palestinian homes where we spent the night and then regrouped and traveled to Deheisha. Omar Hmidat, the son of the local imam, came to greet us and be our tour guide. Hmidat, 26, is majoring in media studies at Al-Quds University as part of the Bard College honors program. His thesis is on “the visual narratives of Palestinian political expression” – something that was evident from his in-depth knowledge of the murals that dotted the encampment.

The camp itself was created in the aftermath of the Arab-Israeli War when, in 1949, refugees from Hebron and 45 villages west of Jerusalem sought temporary asylum. According to official statistics from 2015/16, there are as many as 15,000 people living on an area of one square kilometer. Over the years, however, the population has expanded rapidly and as many as 22,000 people now live immediately outside the camp, Hmidat said.

Though the camp is largely comprised of permanent structures, the UNRWA is still operative in the area.

While the community is less reliant on the UNWRA for aid than it once was, Hmidat explained to us that its presence is also symbolic. It is, he said, “proof of the right of return” for Palestinians.

The meaning of “right to return,” he continued, has evolved from the refugees’ right to resettlement in their former homes to a broader understanding of access and basic civil liberties. Deheisha is located between Zone A, governed by the Palestinian authority, and Zone B, which is under joint Israeli-Palestinian security control.

After touring the refugee camp with Hmidat, we went to his home where we met his father, Sheikh Ibrahim Hmidat. He took time to explain to us that life was hard and dispiriting for the residents of Daheisha, but that Islam has helped to sustain the community, giving it hope for the future.

After lunch, we met with Rabbi Yair Kahn at Har Ezion Yeshiva, in the settlement of Alon Shvut. A student of two luminaries of the Modern Orthodox movement, Joseph Soloveitchik and Aaron Lichtenstein, Kahn serves as the editor of the yeshiva’s virtual Bet Midrash Talmud series.

The rabbi opened the conversation by saying, “To be Jewish is to be part of a nation.”

Through references to the books of Esther and Ruth, it quickly became apparent that Kahn derived his authority from religious texts, and not international agreements and treaties. Where the people of Deheisha spoke in terms of checkpoints, economic self-determination, and water rights, Kahn repeated time and again about “providence” and “the hand of God” in guiding Jewish settlement of the West Bank.

Alon Shvut is a settlement in Zone C, administered by the Israeli military, but is considered part of what would be the future state of Palestine. As such, most of the international community considers its existence illegal under international law, a claim disputed by Israeli government officials who cite the existence of a Jewish community there before 1948.

Although the rabbi was reluctant to speak personally to issues of politics or theology, he stressed the importance of tolerance and, to some extent, pluralism, at the yeshiva.

“What we are taught here is complexity – that there are different opinions,” he said, “and that you must respect them even if you disagree with them.”

After leaving the yeshiva, we were joined by a rabbi of the more progressive Reform movement of Judaism, Rabbi Arik Ascherman.

Ascherman, the former president of an organization called Rabbis for Human Rights, now heads an organization called Torah of Justice. He led us to a Bedouin encampment at a West Bank community called Susya.

The Bedouins at Susya were uprooted from their community in 1986 when an ancient synagogue was discovered on their land and expropriated by Israel. Since then, a legal battle has ensued over rights of ownership and settlement. Before the election of Donald Trump in the United States, Ascherman explained, the Israeli authorities had made accommodations and allowed the Bedouins to build on their farms, but over the past year these talks have fallen apart. We had to chance to meet some of the families affected by the dispute, and they informed us, with Ascherman translating, that the Israeli army had dismantled their makeshift homes seven times in recent years. This encounter demonstrated the determination of displaced families to stay on their land, but also the precarious existence of Palestinians living in Zone C, where Israeli civil and security control is an everyday reality marked by checkpoints, outposts and growing settlements.

Speaking to the sectarian nature of the conflict and why he does this work, Ascherman reminded us of the need to exercise individual acts of kindness to chip away at harmful stereotypes between different peoples.

“I will do it again and again,” explained Ascherman, recounting an occasion when he was beat and arrested by the Israeli Defense Forces, “for a young boy to say, ‘A tall Jewish man in a kippah came to my rescue and told me not to be afraid,’ because if there’s any hope for any of us, it is that [Palestine’s] children are mine, too.”

Photos from day 5:

The type of news no one ever reports

HAIFA — If we started our journey through the Holy Land with a look at ethnic minority refugees in South Tel Aviv, we continued it today with a visit to two of its smallest minority religions, the Bahá’i and the Ahmadi Muslims.

Our first stop: The Baha’i World Center. There are not many Bahá’ís – only about five million around the world – but, according to our Baha’i guide, Rodney Clarken, it is the second most widely distributed religion, right behind Christianity.

The Bahá’í faith is a religion of all religions. All beliefs are considered valid and the Bahá’ís see the world’s major religions as chapters in God’s teachings. There are no clergy or churches, but they do have one place that’s especially sacred – this region in the north of Israel, where the remains of two important figures in the faith, the Báb and Abdu’l Baha, lay. Here we were, standing right there, most of us in awe.

Full disclosure: I spent some time with a few Bahá’ís in New York, so I knew anecdotally what to expect in terms of the beauty of the Bahá’í World Center. Like some of the Bahá’ís back in the States, Clarken, a retired professor from the U.S., told us how honored he felt to live and work there as an archival assistant. Clarken, who has volunteered there for six years, did not initially want to do it. In fact, he said he came as a “sacrifice to God.” But now, he says that he’s never been happier.

Clarken will work at the Bahá’í World Center for one more year, then he will leave Israel. None of the Bahá’í volunteers are permanent residents of the Holy Land, nor are they allowed to be. That’s the way the founder of the faith, Bahá’u’lláh, wanted it.

That means Haifa is home to a faith with no community there, and it’s also home to another religion where its only community in Israel is in that city: Ahmadiyya. The Ahmadis – as the worshippers are called – consider themselves to be a sect of Islam, though they do not believe that Mohammed is the final prophet, as orthodox Muslims do. Seventy to 80 percent of the 2,200 Ahmadis in Kababir, a neighborhood in Haifa, are from one clan, the Oudeh family, which converted to Ahadiyya four generations ago. So was the next man we met with: Muad Oudeh, the Secretary General of the Ahmadi Muslim community of Kababir.

Oudeh’s favorite question might be “why?” (really, he should be a journalist). When we arrived at the mosque, he immediately asked us why worshippers come to places like that one to pray. We all guessed: “To talk to God?” “To be with the community?” No, he said. He offered a reason of his own: worshipping at a mosque is coming to meet God.

Oudeh, an energetic man with plenty of stories, tackled another big why: Why the division and hatred between different religious groups?

“We have a huge issue in interrupting God’s words,” said Oudeh. He said the way certain passages are understood (or misunderstood, perhaps) create division.

But when it comes to physical places, there is in fact a line of division for Oudeh. Haifa is the “Holy City,” and it does not belong to Israel, he said.

“The Jewish state is not my state,” said Oudeh, who identifies as Palestinian. “The anthem, the flag…I am not inside.”

Oudeh said he often meets with leaders of different faiths to talk about the differences they have. But he’s tired of talking. He said that once, on a visit to Jerusalem, he proposed walking down the street with a rabbi, holding hands. A Muslim and a rabbi in unity, he said. Think about the example that would set! The rabbi wasn’t ready yet, but Oudeh said that he is.

But the unlikely sight of a rabbi and imam embracing is a common occurrence in a city that is just a 30-minute drive from Haifa, the city of Acco. During our visit to Acco this afternoon, we gathered in a local theater to meet that rabbi and imam. When Imam Samir Assi entered the room, Acco’s Chief Rabbi, Yosef Yashar, rose from his seat. The two men embraced with hugs, kisses and handshakes, like two long-time friends who hadn’t seen each other in years. They truly are friends – best friends, actually, if you ask Yashar. They serve as an example in Acco – where Arabs make up more than 30 percent of the population – that Muslims and Jews can be neighbors peacefully.

“There is no secret recipe,” the rabbi told us in Hebrew, with Professor Yarden serving as a translator. If everyone respects “basic humanity of our neighbors, we can live together.”

Assi, who until recently was the imam of the second-largest mosque in Israel, agreed. “I need to understand people who are different from me,” he said, also in Hebrew. “It all begins with showing respect to one another.”

While there is still tension between the communities and incidents of incitement in Acco, Yashar and Assi believe their city can be a model for coexistence.

“This type of news, no one ever reports,” Assi said.

For a room full of journalists, this was a good lesson. Later that night our group drove to the northern Israel city of Tiberias where we set up our pop-up newsroom in the Restal Hotel. Among the pictures and stories that we posted on our website, Godland, were the images and words of the rabbi and the imam of Acco.

Photos from day 2:

Halal and a holy book: The Islamic Center at NYU serves up weekly spiritual discussions

NEW YORK — Just after 7 p.m., Sheikh Faiyaz Jaffer enters the fourth-floor conference room at the New York University Islamic Center on Thompson Street in Lower Manhattan. He has a MacBook in one hand and a copy of the Quran in the other. This is Jaffer’s weekly halaqa, a religious gathering for the study of Islam and the Quran.

Jaffer pulls a regular crowd – those who have gathered tonight came to hear his interpretation of chapter 35 of the Quran. He is a renowned scholar of Islam and a sheikh, which differs from an imam by the virtue of having had a seminary education. Jaffer takes his position on the floor and opens his MacBook as the nine other members of the group gather in a circle around him, pulling out their phones and Kindles to read along. They sit on a gray carpet, propped up by dark blue floor chairs. They face out the full-length windows where the Empire State Building is just visible beyond the Washington Square Arch. In the middle of the circle, an iPad supported on a tripod is streaming the event live on Facebook.

Jaffer begins by reading verse five of chapter 35 from the MacBook. The Quran lies on the floor next to him. He reads in Arabic and notes that this verse asks believers to reflect on the concept of “dunya,” the Arabic word for world. Jaffer explains the root of this word comes from the meaning “very low,” which reminds believers that the human world is the lowest of the low. “We as a human being are not only to focus on this real corporeal dimension,” Jaffer says, since in this verse Muslims are reminded there is something beyond this earth that is of a greater nature.

“Surely Satan is your enemy, so make sure you treat him as an enemy,” says Jaffer, moving on to translate verse six. In Islam, Satan is not just one entity but has many forms and exists in humans. Reading this verse in the context of the last, Jaffer says that God reminds believers that if they are deceived by this earthly world, they may fall into the trap of Satan. When you see people cutting corners and focusing on material things, you should steer clear, Jaffer warns.

In the final two verses of the evening, verses seven and eight, Jaffer discusses the role of God in punishing those who do fall into the trappings of the corporeal world and Satan. The balance lies with the believer, he concludes. God will welcome those who take a step towards him but your faith has to be strong. God doesn’t just forgive anyone.

After half an hour, Jaffer closes the conversation with an Arabic saying and turns off the iPad’s stream. The groups ask questions and reflect on the teachings.

And then it’s time to eat! Individual portions of biryani have been delivered from BK JANI, a Pakistani restaurant in Brooklyn. The night's menu includes a slightly spicy chicken curry served with rice and a yogurt sauce. The group moves to another section of the room and sits cross-legged, eating from takeaway containers using plastic forks. There are two big trays of Dunkin’ Donuts to go with the biryani, which is fortunate, as several members of the group find the dish too spicy. One woman drowns her portion in the white yogurt sauce but still doesn’t manage to finish the meal.

Although the group meets at NYU, few are affiliated with the university. Muhammed Jawad, 32, has been coming to the center for two years and drives for an hour from his home in central New Jersey to be here. “I get to speak to a faith leader who I can identify with,” says Jawad. “I can’t represent myself until I know what I believe in,” he says, explaining that the halaqa gives him a better-rounded understanding of his faith. He uses these lessons to help him better talk about Islam to his peers, particularly as he feels the religion is often misrepresented.

Ali Alvi, 37, is an entrepreneur and also uses the lessons of the Quran in his daily life. Tonight, the message of remembering not to be distracted by those seeking only earthly vanities has particularly resonated with him. “I’m going through a situation with someone who’s doing that,” Alvi says. Studying the Quran tonight has reminded him to steer clear of that individual, he says, “because Satan is all around.”