16 Israelis and Palestinians Talk Identity, Before Elections : A Photo Essay

As published in The Forward

In Israel, Judaism alone boasts a spectrum of denominations, affiliations and nomenclatural religious-national identifiers. 93 percent of Israeli Jews would say they are proud of their Jewish identity, according to a recent Pew study, but the way they understand and describe that identity - and what it means to be Jewish - can vary drastically, whether it be “Israeli Jew” or “Jewish Israeli”, along with labels like “ultra-Orthodox”, “modern Orthodox”, “Conservative”, “Masorti” or “secular” to name a few.

But how do other religious communities identify themselves in Israel and parts of the Palestinian territories?

We travelled from the northern Druze village of Beit Jann to a cluster of Jewish settlements in Gush Etzion, to interview and photograph 16 people of different faiths about the way they self-identified. In a land where even calling a country “Israel” can be construed as a political statement, those we interviewed described themselves very intentionally while describing their relationship with the state.

Our interviews came at a critical juncture as the country prepares for what is expected to be one of the most closely contested Israeli elections in recent political history. The incumbent, Benjamin Netanyahu of the Likkud party, is looking to win his fifth election on April 9th and eclipse David Ben Gurion’s record as the nation’s longest-serving prime minister. He is challenged by the newly-formed centrist Blue and White led by Yair Lapid and former IDF chief of staff Benny Gantz.

With the growing political clout of extremist parties on the right like Jewish Power (“Otzma Yehudit”), this won’t be the first time the country’s identity has become a topic of national discourse. The Knesset’s passage of the nation-state law last May, which affirmed that “the right to exercise national self-determination” in the State of Israel is “unique to the Jewish people,” has provoked similar discussion and controversy.

In this election, identity is everything.

Maayan Mankadi, Beit Horon

Maayan Mankadi is from Beit Horon, an Israeli settlement located a few kilometers away from Ramallah. Mankadi identifies as a modern Orthodox Zionist, and recently got married in Jerusalem. “I’m at the Kotel to pray and to thank God for helping me get to where I am now,” she says. “I appreciate the sanctity of the Torah, but I’m also a regular member of the country’s workforce. We earn a living and serve in the army or complete national service. It’s somewhere in the middle of the two extremes we find in Israel.”

Sawsan Kheir, Beit Jann

Sawsan Kheir is a psychology PhD student at the University of Haifa. Born and raised in Peqi-in, a Druze village in the Galilee, her research focuses on the effects of modernization and the value of faith in Muslim and Druze students across Israel. She defines herself as Druze, Arab, and Israeli. “Since the establishment of the State of Israel,” she says, “the Druze have been loyal to the government and had very positive relations with the Jews because of our shared history of persecution. There is a mutual understanding.” With the recently passed nation state law, Druze like Kheir are nervous. “We are loyal to the land we are born into,” she says. “There are three basic elements of our faith: the land, honor, and religion.”

Avi R, Haifa

Avi, a security consultant from Haifa, considers himself a masorti (traditional) Jew. “I go to synagogue for all the festivals and keep our traditions,” he says. “I am first Jewish and then Israeli.” For Avi, his identity won’t change in the upcoming elections. “My family and I always vote for Likkud.”

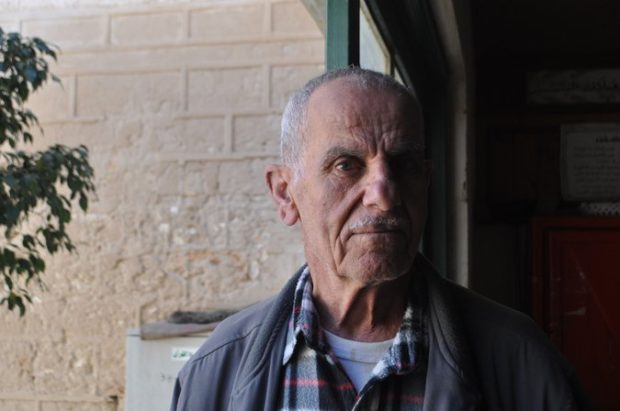

Sheikh Jamil Khatib, Beit Jann

Sheikh Jamil Khatib is one of Beit Jann’s four imams. “I am an Israeli Druze,” he says. “First, I am a Druze through my mother and father, then I am an Israeli because I am connected and attached to the land of the State of Israel. I am prepared to do anything for my country and to perpetuate its existence.” Politically, Khatib explains, the Druze in Beit Jann are somewhat divided. “Some support Likkud, some support Meretz, some follow Chadash - you see us in every single political party and this election won’t change that.” Khatib himself is committed to Druze education and cultural workshops for his community, and served as principal at a local elementary school before becoming an imam.

Chaftzivah Bitton, Tzfat

Chaftzivah Bitton lives in Tzfat, and works as an advisor to newlyweds and a supervisor at her local mikveh. “I am an Israeli from a religious household,” she says. “My father was a rabbi, my husband is a rabbi, and we are continuing the traditions of the Jewish people. My identity will not change at all in the upcoming elections. I am Jewish, religious, and Israeli.”

Sheikh Sami Abu Anas, Nazareth

Born and raised in Nazareth, Sheikh Sami Abu Anas is the head imam at the city’s White Mosque. “I am a Muslim Palestinian, living in the State of Israel,” he says. “Though I would always describe myself first as a Palestinian, I was born in Israel. I respect the laws of the state, and respecting the state you live in is a principle that goes all the way back to the time of the Prophet himself.” Anas’ mosque is open to all, but he fears that increased polarization has pushed Israeli Jews and Arabs to more extreme sides of the political spectrum. Nazareth is the largest Arab-majority city in Israel, and to Anas, this indicates that many different kinds of people can live in the same place. “I truly hope that whichever government is formed after the elections makes us feel more included, even if it is Netanyahu’s government. I also have the freedom to express myself here as a Palestinian Muslim, unlike in Gaza or Egypt or Saudi Arabia, for example.”

Sami Shalsha, Nazareth

Sami Shalsha is a caretaker of the White Mosque. “I am an ordinary and simple human,” he says. “I don’t like discrimination or hate, and my religion teaches me that we all must live together in harmony, whether you are an Arab or Israeli or English or Jew or Christian or Muslim or whatever - it does not matter.” Though he lives just around the corner from the White Mosque, Shalsha is originally from the north. “I take care of the mosque every day from 10 in the morning until 7 at night…I also guide the tourists who come visit talk about the history of the mosque. I try and change their perception of Islam because some of them see groups like ISIS as Islamic. ISIS does not represent Islam, and Islam is not a religion that condones murder.”

Shmuel Zengoltz and Matanya Guetta, Jerusalem’s Old City

Shmuel Zengoltz and Matanya Guetta know each other from yeshiva, and come to the Old City together almost every week. They both identify as Haredi (ultra-Orthodox), and Zengoltz, originally from Tiberias, sees his Israeli and Haredi identity as inextricably linked. Guetta feels slightly different: “I am from Jerusalem,” he says. “I am first a Jew, then a Haredi, and then an Israeli, because Judaism has been around the longest, before Haredim and before Israel. No election will change my identity.”

Ahmed, Nazareth

Ahmed makes some of Nazareth’s best knafe, doling it out from a small corner of the famed Mahroum sweet shop. “We are all human beings at the end of the day,” he says. “I don’t like that everyone categorizes themselves as either Israeli, Palestinian, Christian, or Muslim. We all belong to the human race.”

Dr. Maria Khoury, Taybeh

“I identify as a Palestinian in spirit, but I’m Greek Orthodox in blood,” says Dr. Maria Khoury, a Taybeh resident. Along with her Palestinian husband and his family, Khoury runs the popular Taybeh Brewing Company, the Taybeh Winery, and The Taybeh Golden Hotel. “No matter what the election results are in Israel, I think our situation here in the West Bank will pretty much stay the same. I do not think the wall is going to go away. I do not think the checkpoints will go away. I do not think the Israeli settlements are going to go away. We suffer from the Israeli occupation because our freedom of movement is limited.”

Pastor Munther Isaac, Bethlehem

Serving at the Christmas Lutheran Church in the old city of Bethlehem, Pastor Munther Isaac is acutely aware of his own religious and national identity. “I am a Palestinian Arab Christian,” said Isaac. “I am a follower of Christ. And when I think of the elections, I just hope that people choose someone who is willing to have a serious conversation about making peace. Right now, current Israeli rhetoric is reflected by the recent Nation State law. I’m hoping for people who will make the country more inclusive.”

Isaac Simanian, Tel Aviv

Isaac Simanian’s spice shop in the bustling Levinsky market is always full of customers. “My parents were born in Iran,” he says from behind the counter, “but I am an Israeli Jew. I wear a kippah, but it’s important to me that all religions are welcome here.” Simanian plans to vote for the Likkud party in the upcoming elections. “I choose Netanyahu,” he adds. “No one is better than him.”

Zahi Khouri, Ramallah

Born in Jaffa, Khouri is one of Ramallah’s best-known businessmen. He has lived all over the world, and is the founder of the Palestinian National Beverage Company and produces Coca-Cola for the region as well. He opened up the Palestinian Beverage Company as a way to not only encourage local business in the area, but also to provide hope to the community. He is outspoken against Israeli occupation, but doesn’t think the elections will change much. “First, I am a human being,” he says. “Second I am Palestinian. Third, I am a Christian.”

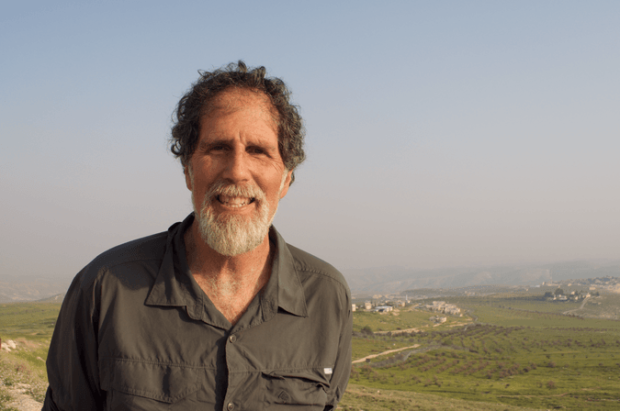

Rabbi Dov Berkowitz, Shiloh

Born in Chicago, Rabbi Dov Berkowitz now lives in Shiloh, an Israeli settlement almost 30 miles north of Jerusalem. “I consider myself a Jew, a father, and a husband,” he says. Upon moving to Israel, Berkowitz never intended to move to a settlement. When he and his wife first arrived, Berkowitz says he was “the leftie here - the peacenik.” But after the first intifada, Berkowitz started to change his mind. “I deeply believe in creating peace with the Palestinians,” he says. “For me, Zionism means many things, but the bottom line of Zionism is that the Jewish people came back to Israel not to be killed.”

Omar Hmeedat, Dheisheh Refugee Camp

Omar Hmeedat calls himself a Palestinian atheist. “I do not support any political party,” he says. “I am even more critical of their agenda and the way they work. I also do not think this conflict should be religious.” Though he does not live there now, Hmeedat grew up in the Dheisheh Refugee Camp, just a few miles from the old city of Bethlehem. He is now actively involved in non-political community organizing and urban planning research. At Al-Quds University, Hmeedat is majoring in media studies. “The elections won’t change anything,” Hmeedat adds. “I am Palestinian and will remain Palestinian. Whether I live in Palestine, Israel, or in Europe. This won’t change my identity.”

Omar Hmeedat calls himself a Palestinian atheist. “I do not support any political party,” he says. “I am even more critical of their agenda and the way they work. I also do not think this conflict should be religious.” Though he does not live there now, Hmeedat grew up in the Dheisheh Refugee Camp, just a few miles from the old city of Bethlehem. He is now actively involved in non-political community organizing and urban planning research. At Al-Quds University, Hmeedat is majoring in media studies. “The elections won’t change anything,” Hmeedat adds. “I am Palestinian and will remain Palestinian. Whether I live in Palestine, Israel, or in Europe. This won’t change my identity.”

Rabbi Arik Ascherman, Gush Etzion

Rabbi Arik Ascherman, the founder of Torat Tzedek (Torah of Justice) and previous President and Senior Rabbi for Rabbis for Human Rights, is recognized around the world for his commitment to human rights and social justice in the region. He is originally from Pennsylvania, but he moved to Israel in 1994. “I identify as a human being,” he says, “and my Jewish identity and faith are not my wall with the rest of the world, but my bridge.” Ascherman is committed to inter-faith dialogues, and has previously been on trial for acts of civil disobedience. “As a human rights leader,” he adds, “I don’t tell anyone how I’m voting and I don’t affiliate with any political party, but I will vote and I will ask others to vote for a party that is honoring God’s image and every human being.”

Jonathan Harounoff is a master’s student at Columbia Journalism School, an alumnus of the Universities of Cambridge and Harvard, and an incoming FASPE Fellow. Some of his work has featured in The Jerusalem Post, Religion News Service and The Harvard Gazette.

Leah Feiger is a religion, gender, and culture writer living in New York City. She is currently an intern at The Forward, and was previously a freelance writer based in Kigali, Rwanda. Her work has appeared in Ozy, Fodor’s, and Culture Trip, among others. Follow her on Twitter @leahfeiger.

Leah and Jonathan reported this story during a trip to Israel as part of a Columbia Journalism School religion reporting class that is sponsored by the Scripps Howard Foundation.

This story "16 Israelis and Palestinians Talk Identity, Before Elections: A Photo Essay" was written by Leah Feiger and Jonathan Harounoff.

Photographs courtesy of Leah Feiger.

Day #6: Jerusalem

JERUSALEM – Our day on Friday started just inside of Jaffa Gate, one of the seven entrances to the Old City of Jerusalem. We also had an extra addition: Professor Ari Goldman.

The night before, some of us had celebrated Purim by dancing to Israeli music and eating Israeli-Yemenite pastries on the streets surrounding city’s Mehane Yehuda market. Even the next day, as we stood outside Jaffa Gate, people were still carrying holiday gift baskets and dressed in costume. But, instead of continuing our Purim celebrations, we were preparing to explore the holy sites of the Old City.

Arnita Najeeb, our tour guide for the morning, started with the Jaffa Gate to give us a sense of Jerusalem’s complex and extensive history. The gate was originally constructed by the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century and was eventually expanded to include a bridge, used by Kaiser Wilhelm II, to enter the city.

From the gate, we were led through the Armenian Quarter, where we learned about the city’s four quarters. While Jerusalem is split geographically into Christian, Muslim, Jewish and Armenian quarters, residents are not exclusively tied to these areas. Jews can and do live in the Muslim Quarter and Armenians do not have to live in the Armenian Quarter.

We eventually arrived at Zion Gate, one of the newer entrances to the city. The gate was officially re-opened in 1967 after the Six-Day War, but the craters and cracks around the arch stand as evidence of the conflict the gate was witnessed.

In telling us the history of the old city, Najeeb presented us with a theme that still resonates today. Jerusalem is, and has always been, a city characterized by the constant building up and tearing down of walls.

“Here, walls do not help people,” Najeeb said. “They make it difficult for people to work and they make people more stressed.”

We then visited the site of the Last Supper, the Cenacle or the Upper Room. In the room, a tour group from Indonesia cried out hymns in a circle, worshiping one of the holiest sites in Christianity.

Located above King David’s Tomb, the Cenacle is also a demonstration of how one site can be overtaken and refurbished by different religions. Across the room, Arabic inscriptions can be seen and a dome-like structure sits at one corner. In the 12th century, while Jerusalem was under Ottoman rule, the Cenacle was converted into a mosque.

Discussions about the intersections of religions in Jerusalem continued outside of the holy sites. Between the Jewish and Armenian Quarters on Ararat Street, Najeeb had us stop. Behind him stood both a mosque and a church. In front of him, back on Chabad Street, were Jewish homes.

“Do you see people fighting here?” Najeeb asked us. “People can live together in peace.”

Weaving our way down the cobbled streets and steps of the Jewish Quarter, we eventually arrived at the Western Wall.

In front of the wall, Jonathan Harounoff, a fellow journalism student, gave his personal insight into a Jewish ritual: wrapping the Tefillin. Two sets of small boxes with leather straps, the Tefillin is meant to be wrapped daily. One goes over the head and one is wrapped around the arm.

“It symbolizes your relationship to God,” Harounoff said. “It’s the ultimate mitzvah, or good deed.”

After viewing the main section of the Kotel, some of us broke off to observe the southern part of the retaining temple wall. The southern part is often referred to as the egalitarian section, as both men and women can pray and read Torah together and without any separating barrier.

The egalitarian section can only be accessed through the Davidson Center, the archaeological site adjacent to the Western Wall. While the Kotel is free, a ticket to the Davidson Center and the egalitarian section costs 29 ILS for an adult ticket.

The southern section is home to one of the best views of East Jerusalem, spanning from the Mount of Olives to the walls of the Jewish Quarter. However, only two other visitors were taking advantage of the view and the egalitarian section. Unlike the Western Wall, at midday on Friday, no one was praying or reading Torah.

A few hours later, after we broke off to report on our own stories, we regrouped at the Western Wall for Shabbat service. The mood of the wall had shifted. There were many more observers than tour groups, and the Kotel began to feel like a true place of worship, rather than a tourist site.

In the women’s section, a line of women stood up at the barrier to hear the men chant and sing Shabbat prayers. A few women sang along and clapped their hands, while others stayed silent and focused on the wall. The praying was individualistic and each woman kept to herself.

The men’s side of the Western Wall featured small groups of men, praying and dancing around tables. Their chants were loud and relatively in sync, although some went at their own pace and lagged behind.

Once they finished their prayers, each of the women would back away from the wall with slow steps. Each woman’s gaze never left the wall.

After the Sabbath prayers at the wall, we made our way up a small hill to our hotel, the Sephardic House Hotel in the Jewish quarter. There we had a “family style” Shabbat dinner with a number of guests, including Professor Goldman’s nephew, and Columbia Journalism Professor Gershom Gorenberg’s wife and son. Our guide and educator, Ophir Yarden, also invited his wife and four of his children. As students, we were treated to a traditional Shabbat dinner, complete with the blessing of the bread and the wine. An hour in, Ophir interrupted our conversations and presented us with a question.

“What is your holy envy?” Ophir asked the table. Theorized by Krister Stendahl, holy envy refers to one’s willingness to admire aspects of other faiths. Ophir took this further, asking us if there were any rituals or practices in other faiths that each of us almost wish we could partake in.

While others took time to reflect on the rituals of other faiths, his son answered immediately.

“I’m jealous that others don’t have to wrap Tefellin,” he said.

Day #4, Part II : Shilo

The second part of our day began with a half hour drive through rocky green hills to Shilo, an isolated Israeli settlement 28 miles north of Jerusalem.

Flanked by Israeli flags, our bus moved slowly up a hill, turning right at a brown welcome sign that read, “Ancient Shilo,” a historical site believed to be the resting place of the tabernacle before the establishment of the Jewish temple.

Today, the settlement lies adjacent to the ancient city, and is home to approximately 400 hundred Israeli families. It’s also part of what’s known as “Area C,” a section of the West Bank under Israeli security and civilian control.

After entering the settlement, we followed the green Hebrew road signs filled with biblical echoes, strode past an empty children’s playground and an array of bright yellow sunflowers to meet Rabbi Dov Berkowitz, a resident of Shilo. The gray-bearded rabbi, who has spent time in Manhattan near Columbia University, now calls this settlement his home.

He led us across the brown tile floors of his house, and we joined him in a circle across the living room.

As he spoke, noises from the nearby kitchen filtered across the room. The rabbi’s wife, Tzippi, swiftly chopped white onions, preparing food - from toasted granola, chickpeas, to vegetable soup - for the upcoming Purim celebrations. During Purim, it’s custom to give food to family and friends, Tzippi said. It’s something she often does here in Shilo, and even in Jerusalem.

Downstairs, the rabbi spoke candidly about his journey to the settlement. Stroking his beard, he recollected memories of his first visit, a Shabbat experience in the town. “We loved the people,” he said. It was not ideological – at first. But then, the Palestinian uprising known as the first Intifada happened 1987-1993.

He remembered Molotov cocktails damaging settler cars during the uprising. “Nothing like that had ever happened,” he said. The period took him through a moment of “re-organizing” his mindset, “Zionism is many things, but the bottom line of Zionism is the Jewish people came to Israel not to be killed.”

But in Shilo, settler motivations are mainly religious. “This is ground zero of the promised land,” said Ophir Yarden, referring to the historical Judea and Samaria promised to the Israelites in the Torah, the Jewish sacred text. And according to the Rabbi, more and more Israelis are looking to rent space in Shilo.

The rabbi was quick to acknowledge the sensitivity of the settlement issue. “Settlements do not help the dialogue. Settlements do not bring peace,” he said. But without the Palestinian acceptance of “the state of Israel as a legitimate Jewish state,” he sees an impasse.

(Image of Shilo, public domain)

Day # 2, Part II : Acco

ACCO – It is quite unusual to see rabbis and imams hug as dear friends, but in the ancient city of Acco, the unlikely has become the ordinary.

Rabbi Yosef Yashar, the Chief Rabbi of Acco, and Imam Samir Assi, a retired Imam of the city's al-Jazzar Mosque, spent the afternoon telling us about their dear friendship and commitment to interfaith unity. When Assi walked in the door, Yashar rose from his chair to embrace and kiss the imam like a brother. “In Acco,” said Yashar, “we’re different from other places. We believe each person — no matter their lifestyle or religious background — has the right to live as she or he sees fit.”

Acco, a port city in northern Israel just a 30-minute drive from Haifa, is known for its gleaming white stone city walls and intricate mosaics. Though the physical beauty is noticeable, it’s the city’s tolerant population that makes it remarkable. “We hate only one thing in Acco,” said the rabbi. “Hatred. It sounds like a slogan, but we really mean it and live by it.”

Over the past 20 years, Yashar and Assi have formed a genuinely close relationship, which, they say, has bolstered the relationship between their respective faiths. They told stories of visiting each other’s houses of worship, speaking at religious schools, and attending holiday celebrations. For Eid al-Fitr, the holiday that marks the end of Ramadan, the rabbi has traditionally been the second speaker at the celebration in Assi’s al-Jazzar — the second largest mosque in Israel. In Acco, where one third of the population is Arab, peaceful coexistence is a necessity. “Before we have our religious identity,” said the imam, “we have our identity as human beings. That’s what we’re trying to show in Acco.”

In spite of its impressive religious leadership, the city still has its own tensions and difficulties. “We had problems 10 years ago where religious extremists tried to derail the relationship between Jews and Muslims, but we have worked hard to get through it together,” said Assi. Years later in 2014, Assi went to Jerusalem with an interfaith coalition after the terrorist attack on a synagogue in the city’s Har Nof neighborhood that left four dead. Upon returning to Acco, Assi found that vandals, apparently angry at his calls for tolerance, had thrown acid on his car. In 2016, Assi retired from his position at al-Jazzar, but his successor is much less committed to interfaith dialogues. “The new imam is no longer going to go to churches and synagogues to wish people happy holidays,” Assi said sadly.

But Assi and Yashar are undeterred. “Not everyone likes what we do, but we have to do it anyway,” said Assi. “It’s the only option.”

After the meeting concluded, we walked into Acco’s Old City to look at Assi’s mosque. The minaret glowed bright green, and children played football and danced on the street outside. It felt comfortable, even as the cold sea breeze swept over our sunburnt necks.

(Photo courtesy of Eleonore Voisard.)

In Tel Aviv, Jews join with Muslims in vigil mourning New Zealand dead

As published in Religion News Service (RNS)

TEL AVIV — Dozens gathered outside the New Zealand embassy in Tel Aviv Sunday night for a somber candlelight vigil to commemorate the victims of Friday’s (March 15) mass shootings at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand.

“We are a small, bright light at the end of a dark tunnel,” Sheikh Abdallah Nimr Badr said of the event, which was organized by Tag Meir, an all-volunteer Jewish organization dedicated to ending extremist violence in Israel, in collaboration with local Muslim leaders and Israeli-Arab college students at Al-Qasemi Academy.

“We must eradicate this sort of behavior if we are going to live in peace. I hope one day we will be able to walk in the streets feeling safe and free of fear,” Sheikh Badr added.

Other local Muslim and Jewish leaders recited prayers of healing and solidarity in Hebrew and Arabic, while nine Muslim students from Al-Qasemi Academy in Haifa held placards in silence, letting photographs of the slain victims and messages reading “Stop Islamophobia” speak for themselves.

The vigil was part of an overwhelming interfaith response to the attack during Friday prayers, which left at least 50 worshippers dead and dozens more injured. In New Zealand, several synagogues were closed on the Sabbath in solidarity with the Muslim community, and in Pittsburgh, the Jewish Federation of Greater Pittsburgh set up a fund for the victims of the mosque attacks, similar to last October’s crowdfunding campaign “Muslims Unite for Pittsburgh Synagogue,” which raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for families affected by the Tree of Life massacre.

In a meeting with Muslim community leaders in Wellington, New Zealand, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern confirmed that Friday’s attack was the deadliest in the country’s history, adding that investigators were racing to identify the victims of the shooting spree so that they can be buried as quickly as possible, in accordance with Muslim burial tradition.

“When fanatics make the most noise, our voice is silenced,” warned Rabbi Esteban Gottfried, director of the Beit Tefilah Israeli community in Tel Aviv. Midway through his televised speech, Gottfried encouraged the crowd to sing an altered version of the popular song, “Oseh Shalom,” (“A Prayer for Peace”), adding Ishmael, a reference to the biblical patriarch in Muslim tradition and first son of Abraham, to Hu Ya’aseh shalom aleynu v’al kol Israel v’Ishmael (he will make peace for us and for all Israel and Ishmael).