Seeking comfort in crochet

TEL AVIV — On the second floor of a dilapidated building in south Tel Aviv, a burst of color and cheerful energy emerges from a small room. Inside, pockets of chatter in a variety of languages hum through the sunlit studio. About a dozen women, squeezed onto three couches draped in brightly patterned fabric, are crocheting baskets. Others wash dishes or make small talk around a kitchen table.

These women are some of the more than 90 African asylum seekers to find a second home at Kuchinate, an arts collective that empowers women to make household items out of recycled fabric using the art of crochet.

Surrounding the women are dozens of already completed baskets in a variety of shapes and shades lining shelves, stacked in corners, strewn on tables and overflowing onto the floor. Other more ambitious handmade projects, like three-legged stools, rugs and poufs, are scattered among the inventory.

Kuchinate provides the women an opportunity to earn money to support their families. But, more importantly, the collaborative nature of the collective, as well as the soothing act of crocheting itself, enables them to have a sense of stability and community. It also gives them a connection to home. They perform traditional coffee ceremonies for visitors, cook native dishes (I was served a heaping plate of chickpeas and spongy African flatbread called injera) and speak their own languages – Kuchinate means “crochet” in Tigrinya, a language spoken in Eritrea, for example.

Much has been written in recent months about the tens of thousands of migrants living illegally in Israel and Israel’s controversial plan – temporarily on hold – to deport them en mass to Africa. More than three quarters of the migrants are men, but the story of the women is rarely told. Many of the women who entered the country through eastern Sudan and the Sinai Peninsula were victims of torture, sexual assault and human trafficking.

According to the United National Refugee Agency, about 90 percent of the some 38,500 African asylum seekers and refugees currently in Israel originate from Eritrea and Sudan. Others come from Nigeria, Ivory Coast and other areas of Africa. About 17 percent of the population of asylum seekers are women and about half of the women are registered as mothers, according to a report by the Aid Organization for Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Israel. Because of their immigration status, they’re denied access to government assistance programs and health care and are at risk for exploitation. Their struggle is what inspired the creation of the collective.

“I made sure that Kuchinate was born from the desire to provide psychological, economic and social empowerment to women who were in a desperate state of survival,” co-founder Diddy Mymin Kahn wrote on the nonprofit’s website.

Kahn, a South African psychologist specializing in trauma, runs the center with Azezet Habtezghi Kidane, a Catholic nun originally from Eritrea, who provides spiritual support as well as counseling to the women. Known as Sister Aziza, Kidane is well respected internationally for her humanitarian efforts. Her work with refugees earned her the U.S. State Department’s Trafficking In Persons Heroes Award in 2012. In 2016, she and Kahn co-penned a support manual entitled A Guide to Recovery for Survivors of Torture.

Kuchinate volunteer Gina Walker, a student at Tel Aviv University studying global migration and policy, says that the relationship between Kahn, whom she describes as a “powerhouse,” and Kidane, who is more grounded, is key to the success of the collective. “They balance each other,” Walker said. “You need someone to have the big ideas and someone to tame it.”

This month, the voices of the Kuchinate women are being heard all the way across the world in New York City. Through the collective, four women collaborated with Israeli fiber artist Gil Yefman to break out of the basket-making mold and create life-sized crochet artworks for an art exhibition about sexual assault and genocide called “Violated! Women in Holocaust and Genocide.” From inside each piece, decorated with images relating to each woman’s experience, a recording of the artist sharing a personal story will play. The exhibition, produced by the Remember the Women Institute, can be viewed at the Ronald Feldman Fine Arts Gallery (31 Mercer St. in Manhattan) from April 12 to May 12.

Yefman is hopeful more women from the collective will be empowered to use their art as a way to express themselves freely and share their personal experiences. He added that the collaboration gave the women the experience of “stepping outside of the collective while creating a better resonance for the collective.”

Mostly, though, the women work on the craft as a way to support themselves and their families. “They’re in survival mode,” says Walker. “They’re very focused on making money to feed the children.”

Favor Agbo, one of the first women to join the collective and a skillful craftswoman, is quick to lend a hand to her peers. On a balmy Monday afternoon in March, I watched as Agbo closely inspected a half-completed basket. Seeing an error in the carefully stitched handicraft, she removed a few inches of string and turned to the woman sitting to her right who had asked for help.

“Use your finger,” Agbo demonstrated, holding a bright pink-tipped fingernail against the mustard-colored fabric as she expertly maneuvered the needle through the opening she created with her hand. “Don’t pull.” She returned the basket to the artist, who cautiously followed Agbo’s instructions. When the woman completed the small basket later that afternoon, she held it up triumphantly, inspiring whoops and cheers from around the room.

That basket will sell for little more than a few dozen shekels (about $10 USD). “The money is nothing, but we’re happy,” said Agbo.

Walker, who was interviewed in Tel Aviv this spring just before the Jewish festival of Passover, explained that recognizing the struggle of these women, who work in a constant state of instability, is essential now more than ever. “For Passover, we’re celebrating our freedom,” she said. “These are people who are not free."

A version of this story appeared on Religion News Service.

Virtual tourism: The next best thing to being there

NEW YORK & JERUSALEM — “You’re standing at the Dome of the Rock, one of the holiest sites in Israel,” you hear a tour guide say. As that voice explains the significance of the place to people of Muslim, Christian and Jewish faiths, you can see the golden roof glistening in the sunlight. You imagine it’s a warm day in the Holy Land, but you can’t feel the sun on your skin. Perhaps Muslims are entering the Dome of the Rock, or the nearby Al-Aqsa Mosque, to visit the site and pray, but you can’t see or hear them. You can move around the site in all directions, not by turning your head, but by using a computer mouse.

This is the virtual pilgrimage experience.

“For every person who goes to Israel physically, there are hundreds of people who can’t,” said Gary Crossland, the founder of the Octagon Project, a non-profit that produces live-action, virtual tours of Israel and posts them online.

The cost of travel, lack of mobility, and family obligations are just a few factors that might keep people from making the trip, said Crossland, a Texas native, who has traveled to Israel 30 times.

Virtual tourism is nothing new. Pilgrims have always brought back “holy water,” a chunk of earth or a relic to hold on to and share the experience of the journey. Once photography was perfected, tourists brought back pictures of the holy places they’d visited. The embrace of video cameras, gadgets and social media to help people feel closer to the Holy Land is more recent. For years, there has been a 24-hour stagnant live feed of The Western Wall, one of the most religious sites for Jewish people. A few sites accept prayers via tweet to place in the cracks of that wall, an old tradition. On YouTube, there are thousands of traditional video tours, some with photo montages and some narrated.

But with more high-tech devices comes a more immersive experience. Organizations like the Octagon Project use virtual reality to offer that, along with a free, all-access digital pass to Israel. With the help of 360-degree cameras, online tourists can “visit” churches, historical locations, and get a glimpse into the country without a passport, luggage or a plane ticket.

Twenty years ago, Terry Modica, who is Catholic, actually made the 15-plus hour journey from her home in Florida to Israel for a pilgrimage. She saw the Church of the Annunciation, one of the most sacred places of the Christian faith, the Nativity site, where Jesus is said to have been born, and the Dead Sea, the lowest point on Earth.

With a few clicks, you can experience Modica’s journey, too. Back then, she did not have the devices to create a high-tech experience like the Octagon Project, but the 1990s-era photos she collected during the trip are now on her website, Good News Ministries, in the form of a virtual tour. To see the inside of the church, click on the doors and after the webpage loads, you’re inside. Or click for a closer look at the loaves and fish mosaic at the Church of Multiplication, where Christians believe Jesus multiplied enough food to feed a large crowd of followers.

“People once looked at my low-resolution photos and thought ‘oh wow,’” Modica, 63, said. “Now I look at them and say ‘Oh crap.’”

Modica saves the notes from people who still appreciate the virtual journey.

“Although I am a born Catholic,” one virtual pilgrim wrote, “my knowledge of the places where all the miraculous and painful events took place were only imaginary…until now.”

Modica wants to return to the Holy Land to capture the trip for those behind a computer screen. This time, using virtual reality for a more immersive experience.

But some say a virtual trip to Israel won’t do.

“For me, I had to come back,” said Bonnie Bergman, a Boca Raton, Florida native who is Jewish.

On a warm Sunday in Jerusalem, she was back in the Holy Land for the first time in 40 years to meet long lost family members. Bergman stood on the outskirts of the Western Wall in awe.

"It’s emotional,” said Bergman, who is a retired teacher.

That type of meeting is something that can’t be done online. That, and walking into the crowds in the women’s section of the Western Wall to touch what’s believed to be the remains of the retaining wall of an ancient Jewish temple.

While Crossland’s virtual tour company also offers 10-day physical excursions to Israel, he does not think the emergence of the type of technology that may allow virtual travelers to engage other senses — like sight and smell — will have any impact on that business.

“We’re on the bleeding edge of that technology,” Crossland said. But there’s “nothing like being there.”

"When you can actually have boots on the ground and feel the heat on your skin, the packing, the anticipation — it’s a totally different feeling.”

A modern miracle in Galilee: Jews, Muslims and Christians co-exist

TABGHA — Here, on this spot on the shores of the Sea of Galilee, Christians believe that Jesus fed thousands of people with nothing but five loaves of bread and two fish. The Church of Multiplication that was rebuilt in Tabgha in the 1980s was built over a fifth century mosaic that depicts these sacred fish and bread. The church is on a picturesque piece of land with gardens, farmland and a little stream running through the grass to the sea.

The Christian population in Israel is less than two percent but the church draws thousands of visitors each year from around the world. Today, the church and surrounding land are the property of the German Association of the Holy Land. This site is maintained by five Benedictine monks, among them the Rev. Matthias Karl. Dressed in long black robes and wearing circular-framed glasses, Karl noted that while, “We [Christians] are a minority [in Israel], it is true that minorities have problems all over the world – and in theory, in front of the law, we are all equal.”

The theology of equality that Karl espouses is played out in a program at the church called Beit Noah, the house of Noah, a place where people of all faiths are welcome. Generosity is built into Tabgha’s mission, said Karl, because Jesus preformed his most generous deeds on these grounds. For the last 40 years, with a particular growth in the last five years or so, the church has been inviting disabled and traumatized Israeli and Palestinian children to stay on the property. The groups that most commonly come to the church may be either physically or mentally handicapped – particularly children with autism or Down syndrome.

The diverse and all-encompassing nature of Beit Noah seems to fit perfectly within the context of the parables of Tabgha. Rev. John Duffell at the Church of the Blessed Sacrament in New York explained that the main theme of the “feeding of the multitude” is inclusivity. “The entire holy community gathered, not just [Jesus’] followers. He didn’t make any distinctions, and he said to feed ‘all who are there.’ As long as they are good people, it doesn’t matter about the color of their skin, their language or sexual orientation.”

The story exemplifies how Jesus was radical in society for his time, said Duffell. This kind of thought process is how society is going to be made better today, he added.

Paul Nordhausen, the Pedagogical Director of Beit Noah (who is also a German and Christian, but not a monk), said that, “The idea of the program is from the moment the children enter the gates, we try to encourage them to come in as humans first – not as Muslims, Jews or Christians.”

The groups of children come in three different “categories” – from Israel, from East Jerusalem and from the West Bank. They currently cannot bring any groups from Gaza, Nordhausen said, because the current political situation there is too difficult. The groups of children that come from Israeli schools are required to have an armed guard with them at all times. Groups from the West Bank sometimes won’t tell the children they are traveling to Beit Noah, because they don’t know if they’ll be able to make it through the West Bank checkpoints.

“We make people meet on a very basic level here,” Nordhausen said. “I don’t impose any program on them, because first of all, I don’t believe as a German I can tell anyone here what to do. And second, I believe the meetings have to be done by parties in the conflict.” He stressed, however, the importance of leaving the conflict in the outside world, and to focus on having a good time together.

While most groups are special needs, the program does not provide any specialty assistance or healthcare. The offer of the space is that it’s free, but they do not offer any kind of mental health care or physical therapy. They do, however, take volunteers who are mostly German or American to help the program run smoothly.

Carolin Willimsky, a recent German volunteer at Beit Noah, described working at the organization as “the best thing that ever happened” to her. It is a peaceful place, with serene work like feeding animals, gardening, welcoming guests and prayer, she said.

Willimsky recalled one of her favorite times at Beit Noah when the group SOS Children Village from Bethlehem came to stay at the retreat. She and the children were playing a counting game. “We played in Arabic and English and suddenly we starting playing in Hebrew. One of the girls [from Bethlehem] started to count in Hebrew which was very exciting for me. These kids don't have good experiences with Israelis. They just know them as soldiers or as superior power. To play in Hebrew with these kids from Bethlehem meant hope.”

The main “hang out” place for the kids and the volunteers is in the steam in the center of the garden. Everyone can swim, converse and cool down in the hot summer – the most popular time for the Beit Noah program. “Perhaps the different groups can take this sense of peace and diversity back into the outside world after their stay,” said Nordhausen. “But that is definitely not our first priority because this is not a political or even religious thing. It’s to forget the outside world and have fun.”

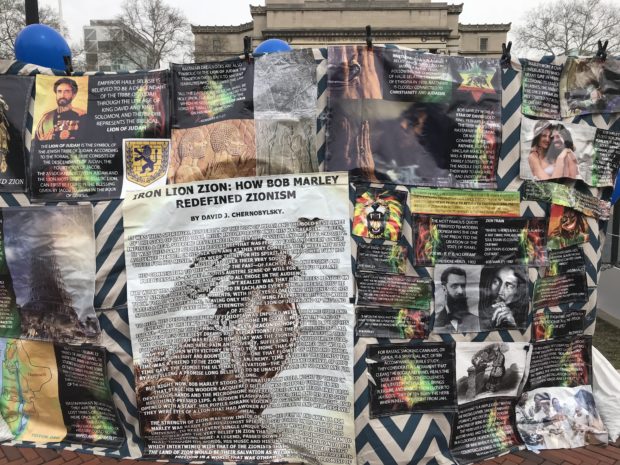

Conflict on campus: Picking up where Jerusalem left off

NEW YORK — Back on Columbia’s campus after 10 days in Israel and Palestine, it feels different. Students are still dashing about to get to classes, but the masses of undergrads seem to slow down just a bit as they reach the center of campus walk, almost as if students are rubbernecking at an accident on the highway. And then I see the flags. The same ones I saw hanging proudly outside buildings and painted all over walls in Israel and Palestine.

The last week in March brings two conflicting events to Columbia: Hebrew Liberation Week and Israel Apartheid Week.

It seems like it’s the same old story from which I cannot escape: us vs. them. Oppressors vs. liberators. Zionists vs. anti-Zionists. As a journalist, I want to hear both sides. So that’s what I set out to do. On one side of campus, in front of Low Library, stand the Columbia Students for Justice in Palestine, Columbia University Apartheid Divest and the Columbia/Barnard Jewish Voice for Peace in front of a makeshift Israeli West Bank Barrier, complete with iconic Bethlehem graffiti from British artist Banksy. On the other side stand the Columbia Students Supporting Israel, complete with flyers and keffiyeh scarves embroidered with the Star of David.

“[It’s] a week of celebration about the connection of Jews and the land of Israel and what Zionism is,” said president of the pro-Israel group, a Columbia junior named Dalia Zahger, 24.

She said the student group hosts a Hebrew Liberation Week every semester.

“I hope [people] come with an open mind to listen, to read and to learn and to hear from us,” she said. “Not to listen from other people about what Zionism means but to ask a Zionist what it means.”

After speaking with her, I feel even more confused about this term and its place in relation to the tensions that exist in Israel and Palestine. In Israel, our class visited the city of Acco to speak to Imam Samir Assi and Acco’s Chief Rabbi, Yosef Yashar. They were friends.

“Best friends,” Yashar said.

After speaking to us about their faiths and their unlikely friendship, I asked how they could be so different and how Yashar could be a Zionist and still be so close with Assi. He looked at me for a second before saying in Hebrew, “It’s about respect for each other.”

That respect is rare. It doesn’t exist in most corners of Israel and Palestine, so how could I expect to come back to New York City and find it here?

I spent some time over at the anti-Zionist corner of campus, staring at the fake Israeli West Bank Barrier. It reminded me of Bethlehem and I missed it. One day while standing at the fake barrier, I heard a couple of students remark in disgust at a puppy wearing an Israeli keffiyeh on the opposite side of the courtyard.

“Ew,” one student remarked.

“Why would you do that to a puppy?” The other agreed.

Zionism, in the dictionary means, “a movement for (originally) the reestablishment and (now) the development and protection of a Jewish nation in what is now Israel.” The movement was established in 1897 under Theodor Herzl. But it’s come to mean different things to different groups since the term was originally coined.

For Zahger, it’s a word that means a connection to her home. She grew up in southern Israel, where she served in the army before coming to study at Columbia.

But for other students it’s almost a trigger word.

I spoke with a student involved with the Columbia University Apartheid Divest and the Columbia/Barnard Jewish Voice for Peace. She asked that I not use her name because of how political the topic has become. She became involved in the organizations during her freshman year after realizing there was something wrong about the way she viewed Palestine.

“I don’t see how it’s okay for one group of refugees to create another group of refugees,” she said. “I also don’t see how I can justify that as the continuation of a state to do anything in its power to maintain a white Jewish demographic.”

For a shrinking group of Palestinians, Bethlehem is still a Promised Land

BETHLEHEM — Salwa Musallam gets to visit the site where Jesus was born nearly every day. As a tour guide with a local nonprofit, she ushers groups through the so-called Door of Humility, using her booming voice to implore visitors to bend at the waist in order to enter the sacred space within the Church of the Nativity. She knows every historic detail related to the church and doles out tidbits of information as her tours move through the multi-room compound. She even stops to explain that Jesus was born in a cave and not a stable, as is commonly thought.

“You are lucky to be going in the birthplace of Christ,” she declares, later adding that it’s important to keep quiet while at the church. It is a lesson she apparently has not learned. “I’m known here as a troublemaker. As soon as someone hears a group laugh, they know it’s me,” she tells her audience. “They’ll kick me out of the Church. One Greek priest, he can hear me even if I whisper,” she adds, jokingly.

With pitch-black hair, lined eyes, and sunglasses perched on top of her head, Musallam stands out from other guides. At 57 years old, her background reads like the passport stamps of a world traveler. She is Palestinian, Arab, Christian, North American and Latin American. She was born in Colombia and moved to Bethlehem when she was six years old. For a while, she and her husband and their four daughters lived in Michigan before deciding to move back to Bethlehem.

Musallam’s family story is very different than that of most Palestinian Christians. While many of them want desperately to leave places like Bethlehem, her family left several times but kept coming back to Palestine. Her story is a reminder that for many Palestinians, even those with options, Bethlehem continues to be a Promised Land, even if it comes with troubles.

The Holy Land’s Palestinian Christian population is a small minority in the region. Palestinian Christians comprise only a tiny fraction of the population but made up around 10 percent of the overall Palestinian population at the beginning of this century, according to Bishop Hanna Kildani, the Latin patriarch for Nazareth.

In fact, a new census estimate by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statics stated last month that out of more than 4.7 million Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, only around one percent are Christian. The main reason for the recent drop is attributed to foreign migration – many Palestinian Christians continue to emigrate out of the country.

“We have this problem of emmigration. Many Christians and Muslims can’t find housing, work, business so we are moving out of the Holy Land,” said Kildani, who wrote his Ph.D. thesis on Christianity in Jordan and Palestine.

Top reasons for emigration among Palestinian Christians include economic and political difficulties, as well as social and religious reasons, according to a recent study by Dar al-Kalima University College in Bethlehem. The study also found that nearly a quarter of Palestinian Christians had family members who have emigrated in the past year and that more than 70 percent did so for economic reasons.

This migratory trend is not new. Financial ambitions and escaping poverty and malady were some of the reasons Palestinian Christians left the Ottoman empire at the turn of the 20th century, wrote Pastor Mitri Raheb, founder of Dar al-Kalima University College of Arts and Culture in Bethlehem, in the recent report. Many settled in New York, while others continued on to places like Brazil and Chile.

Musallam’s father was among those who left. Around 1913, he moved to Barranquilla, Colombia, where some of his other family members were already residing, and took a job selling pants door-to-door.

He settled in Colombia and married Musallam’s mother, ultimately raising a family there. But his daughter retained her Palestinian heritage and married a man from Palestine. At first, she and her husband lived in Michigan but then moved to Bethlehem.

“There is a strong loyalty towards being Palestinian and the land their forefathers grew up in,” said Randa Kayyali, who has written a book on Arab-Americans and has done research on Palestinian Christians.

Today, Musallam’s job as a tour guide with the Holy Land Trust – where one of her daughters also works – keeps her in tune with the religious history of the land. In fact, it was her daughter who recommended her for the job due to her ability to speak many languages, including English, Spanish, French, Hebrew and, of course, Arabic.

But while Musallam came back, most Palestinians want to leave. They have many reasons. Constraints, arbitrary arrests, discriminatory policies and confiscation of land add to a sense of hopelessness and put Christian Palestinians in despairing situations “where they can no longer perceive a future for their offspring or for themselves,” stated the report by Dar al-Kalima. Many Palestinians Christians, therefore, set their sights to Europe, the U.S. and Canada to find refuge.

“Christians are being heavily impacted by the occupation and their livelihoods are being drastically reduced,” said Kayyali, the researcher. “So, if you had the opportunity to go somewhere else, maybe you would take it,” she said, adding that there are Christians in other areas of the world and many might feel that they won’t be persecuted in those places.

More people are leaving the country than are returning, said Marc Frings, head of the Ramallah office for Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, a German political foundation. “What I’m observing is that Christians here are becoming more aware of their minority status even though it’s not new. They’ve been a minority ever since Islam conquered the region. But now they don’t feel protected and are seriously afraid.”

Sami Awad, founder of the Holy Land Trust non-profit and Musallam’s employer, echoed that sentiment, arguing that many Palestinians feel a sense of resignation. “This feeling that Palestinians have is complete hopeless, apathy and that nothing works – diplomacy, violence and non-violence,” he said.

Though Western media rarely explores the plight of Palestinian Christians, Musallam’s situation is different – as a tour guide, she gets to recount her story to any willing listener during her daily tours of the church.

Musallam emigrated to the United States with her husband while he worked as a journalist in Ann Arbor. She still holds American citizenship. But she regrets moving back to Bethlehem. “I miss the States,” she said. “I cried when my husband wanted to come home. I said ‘you’ll regret it,’ and he did,” she added. “As a good wife, for the last 30 years, I’ve been telling him ‘I told you so,’” she said jokingly.

Many of Musallam’s relatives and friends didn’t understand her family’s decision to move back to Bethlehem. “They think me and my family are crazy first when we came back,” she said. “Life is good here, it’s not boring. But, it’s kind of hard.”

Awad, director of the Holy Land Trust, agreed that there are challenges to living in the region. “There are a lot of restrictions on Palestinians. For me, it’s the psychological aspects of daily restriction,” he said, describing the frustrations he feels due to a lack of movement imposed by Israel within the West Bank. “We don’t live like normal people everywhere.”

However, despite the reduced number of Palestinian Christians in the Holy Land, many don’t see the population disappearing completely. “The level of Christian presence will be quite low but it will not disappear, this is clear,” said Frings. “If you ask me openly, I will say there will always be Christian life here because it’s the Holy Land and people are rooted here.”