Stories and a stroll with the Khair family

BEIT SAHOUR — On Wednesday evening, Raja Khair ran up the steps in Bethlehem’s old city to greet the men of our group. Raja is sturdy and has strong hands, thickened by decades of working as a builder. Colin, Matt and Fergus crouched in Raja’s little sedan. Professor Goldman, Dan, Kanishk and Patrick hopped in a cab Raja whistled over for them. Then it was a 10-minute drive to his home in the town of Beit Sahour, just east of Bethlehem. The house was made of thick bricks of the white local limestone ubiquitous in this part of the country. We walked up steps of polished limestone, a stately bannister along one side. Raja built the house for his family over the last 20 years. A second and third floor were completed just last year and provide six extra beds, two bathrooms and a small kitchen for the guests they house year-round.

His wife, Rima, came out and asked if we wanted to eat first or go to our rooms. “Eat first!” we said in unison. She smiled and took us inside where we met two of her three daughters, Amira and Amani, and her son, Joseph. They warmly ushered us over to the dining room table where, much to our surprise, we found a family of four visiting from Dallas. (The Khairs supplement their income by serving meals in their home and, in our case, renting out rooms for the night.) The Dallas family quickly departed and then we were left to enjoy a delicious meal of chicken, rice, eggplant, olives, tomatoes, cucumbers and yogurt. Rima sat with us, a large rosary hanging on the wall behind her, and told us about her life.

Her parents and grandparents fled to Bethlehem from Jaffa during the 1948 War. Raja’s family is from Beit Sahour, which is 80 percent Christian and 20 percent Muslim. Palestinians of these two faiths get along well in Beit Sahour, she explained. They attend each other’s major religious celebrations and lifecycle events. But they almost never intermarry. On the rare occasion it happens, it brings great shame on the families. “To be a Christian in Bethlehem, it’s ok,” she said. “In Nablus and Jenin, it’s more difficult.”

Amani studied public health and nutrition at Al-Quds University, but she couldn’t find a job in her field, so she now works as a teacher. Amira is studying pharmacy but is not sanguine about finding employment in that field. “There are no options for a job,” Rima said. “Eighty percent [of graduates] work somewhere other than their studies.” The job market in Israel is much stronger, but Palestinians need permits and additional exams to qualify.

Rima commutes 40 minutes each day to Hebron, where she teaches Arabic, math and science to second and third graders. There are no official checkpoints on her route to work now, but there were in 2002 when violence erupted and she was forced to stay in Hebron a week at a time. Her mother-in-law cared for the children while she was away and Raja was at work.

Raja goes up to Jerusalem six days a week to his job doing construction work at the White Sisters Convent guesthouse. He has to secure a permit, which is good for six months. But he also has to cross a checkpoint each way, so what would otherwise be a 15-minute commute takes about two hours. He leaves around 5:00 a.m. each morning to make sure he is in time for work at 7:30 a.m. When he had trouble with his permit, he was out of work for a month.

“Each year it’s worse,” Rima said of the Palestinian situation. When she was a child, her father used to drive the family from Bethlehem to Jerusalem, or to the beach. But once Israel built the separation wall more than a decade ago, travel has become too difficult. Palestinians are not allowed to take their own cars into Jerusalem and must either take a bus or walk. “I feel like [when] I’m going, something will kill me,” she said. “I prefer not to go.”

Water paucity was another issue Rima raised. Most homes keep tanks on their roofs because availability is intermittent. “Palestine is surrounded by water, but we are short of water!” she exclaimed.

But this is the only life her children have known. Her two oldest daughters went abroad to be exchange student at a Lutheran school in Germany. Amani called home and expressed amazement that she didn’t need to carry her ID with her. She felt free and happy there, Rima said. “She [didn’t] want to come back.”

Like many Palestinians with resources, some in her family have made the choice to leave. Rima has two brothers who left Palestine because the local university was shut down. They went to England to study and now live in Dublin. Each year they tell her they will return, but they still have not.

But Rima cannot imagine living anywhere else. “I never feel lonely here,” she said. It’s because she is surrounded by family. The Khairs have around 500 family members in Beit Sahour, including 16 nieces and nephews on their street. Her family and the family of her husband are especially intertwined. Rima and her sister married two brothers.

The value of family has been proven to her many times. In 2000, Raja contracted meningitis and nearly died. The family had just taken a mortgage to build their home, and Rima was scared they’d be ruined. But an uncle came in and helped them financially until Raja recovered. “When he was sick, I found everyone beside me,” she said.

For two weeks, Raja was in a coma and was not expected to live. Every day Rima went to pray at the nearby holy site, Virgin Mary’s Well, which is believed to be where the Holy Family stopped on its way to Egypt. On Aug. 28, an auspicious day for that holy site, Rima said, Raja woke up from his coma. Every year since, the extended family gathers to celebrate his recovery. A special dish called drisha, made of beef, wheat and tomatoes, is cooked over an open fire, and the party usually lasts two or three days, Amani told us.

After our supper, the family invited us to join a few dozen neighbors for one of their regular evening walks around Beit Sahour. The hilly eight-kilometer trek took us past Virgin Mary’s Well and the Shepherds’ Field holy sites.

When we returned, we were quite exhausted. Rima made us refreshing tea with lemon, and we listened to Raja play his tabla drum. Soon after, Goldman was ready to return to the Jacir Palace Hotel in Bethlehem, which sits near the border wall. Because of that proximity, Raja asked Rima to join them; he was nervous being a solitary man driving near the wall, and felt it safer to be in the car with a woman. Dan also went along so Raja could practice his English. After dropping off Goldman, on the way back to Beit Sahour, Rima showed Dan her childhood home. It sits just next to a side entrance to the Church of the Nativity, the second-oldest church in the world, built on what is believed to be the site of Jesus’ birth.

The Holy Land: Where churches abound and even the water is sacred

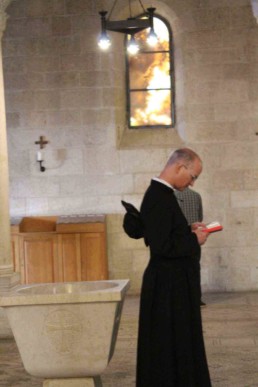

TABGHA — On this very shoreline of the Sea of Galilee, Christians believe that Jesus fed 5,000 people with nothing but five loaves of bread and two fish. The miracle is marked by a church that draws a steady flow of pilgrims who silently crowd the small space, some of them kneeling by the walls and whispering private confessions into a monk’s shoulder. While the modern church on the site was completed in 1982, some of the floor tiles date to the Byzantine period.

The place’s serenity does not match its frenzied history. About 130 years ago, a German Catholic group called the German Occupation of the Holy Land purchased 250 acres along the Galilee’s shoreline – including what is now Tabgha. The pilgrims did not even know what they had acquired: The original Byzantine church had been destroyed by the end of the seventh century, and the land as they found it was obscured by overgrowth. Only archaeological excavations in 1932 clarified the site as that of two major Biblical episodes, but its proximity to the hostile Israeli-Syrian border prevented the church’s construction until 1967 (when Israel captured the Golan Heights from Syria).

Since then, said Father Matthias Karl – one of Tabgha’s five Benedictine monks from Germany – life for Christians within Israel has been generally agreeable. The situation in the West Bank, he noted, is “totally different.” There, Karl said, Israel reneges on the democratic principles it tries to uphold within the pre-1967 borders.

But Tabgha has also known the severity of marginalization: In June 2015, Jewish extremists carried out an arson attack against the church that caused seven million shekels in damage. But the aftermath of this atrocity followed the model of generosity that Karl and Tabgha have long tried to set. The room in which we met, he said, was funded entirely by synagogues from around the world who refused to let the arsonists represent Judaism.

Generosity is built into Tabgha’s mission, said Karl, because Jesus performed one of his most generous deeds on these very grounds. For 40 years, the church has been inviting disabled and traumatized Israelis and Palestinians to visit the church together; it now hosts a full-fledged retreat for up to 80 of those children during the summer.

Indeed, Karl seemed at all points more concerned with his faith’s practical impact than with its symbolic implications. Asked about his robes, he joked that the hood saves him from needing to remember a hat.

Before we departed, Karl interacted with us on personal level. One Catholic member of our group, Liz Donovan, brought along a dozen wooden rosary beads that she bought the day before during our visit to Nazareth. She asked the priest to bless them. He held them in one hand while making the sign of the cross over them with the other hand. “Lord, bless these rosaries and the people who use them,” he said and then offered blessing for our group as we continue our studies and journey.

We then drove south through the hilly desert landscape of the West Bank to a baptismal site on the Jordan River known as Qasr al-Yahud. It was here Christians believe that Jesus himself was immersed in the waters by John the Baptist. We arrived around midday, under a hot son and walked to the river along with pilgrims robed in white, their bathing suits visible beneath the robes.

The water in the river was shallow and murky, the color of clay. A sign read “Border Ahead” in multiple languages, and just a few feet across the river was another country: Jordan. Amid the tourists, on both the Israeli and Jordanian sides of the river, were armed border guards.

Pilgrims were dunking all the way under the brown water and then crossing themselves. Other pilgrims stayed on the sidelines, maybe just dipping their hands or feet into the water. Even though we weren’t there to get baptized, several of our group cooled our feet in the waters, careful not to slide on the slippery bottom.

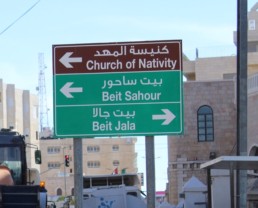

Our visit was brief, as we had to travel to Bethlehem to explore the Church of Nativity. We breezed quickly through a checkpoint as we passed from Jerusalem to Bethlehem. The local Palestinian bus behind us was not so lucky and was immediately pulled over. We drove through a gate in the security barrier built by the Israelis more than a decade ago to separate the West Bank.

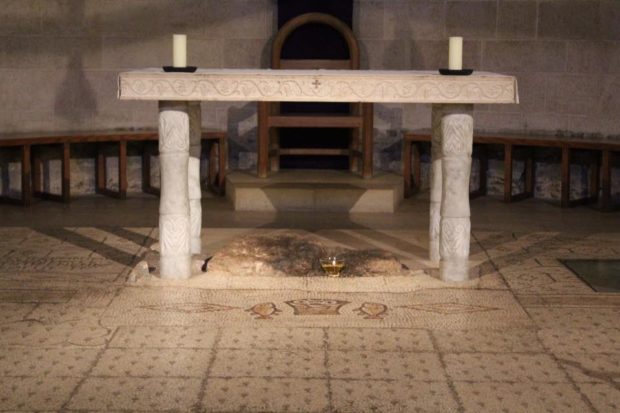

We arrived in Bethlehem and walked through the cobblestone streets. There were many small square buildings stacked on hills. We went up a small staircase in between buildings and found our guide Salwa. Salwa explained the Church of Nativity is the oldest church in Israel/Palestine and second-oldest in the world only to a church in Armenia. To get inside, we went through a “humility door,” a door so small you have to seriously duck to get through.

Inside, there were cool slabs of stone on the floor and the smell of incense was fairly powerful. It was exceedingly ornamented, with many silver chandeliers and candle holders hanging from the ceiling. The walls were covered with elaborate mosaics and colorful idols hung everywhere.

The birthplace of Christ was actually in a cave, Salwa told us, and not in a manger with wood and straw as it is often depicted in the West. She also noted that Christ’s manger was probably made of limestone, a common commodity in Bethlehem at the time. We slowly made it down semi-circular stone stairs with the rest of the pilgrims. In a small cave in the wall was the birthplace, marked by a silver 14-point star. Many people touched the birthplace and some placed rosary beads in the center and crossed themselves. It seemed to be a remarkable and exciting moment for a person of any kind of faith.

Afterwards, we went to the Holy Land Trust, a Palestinian non-profit, to meet the executive director, Sami Awad. The organization works with the Palestinian community at both grassroots and leadership levels to promote non-violent tactics to achieve the peace process. We took our shoes off and walked into a large open room with red pillows low to the ground surrounding the edge of the space. The walls were covered in signs that read “peace” in multiple languages. We discussed various aspects of the Israel/Palestine conflict and Awad explained his personal ideological shift of Ghandi-ian ideology to King-ian, which meant a shift from advocating a change in borders to a focus on universal civil rights. He also explained the three main reasons he thought were fundamentally prohibiting the peace process: Israeli settlements, disagreements on the definition of “peace,” and restriction of movement. He stressed a sense of resignation common in Palestine and the psychological uncertainty Palestinians faced every day.

But more importantly, he said, is understanding others in the conflict: “Jesus said ‘Love thy enemy.’ We have to know who they are, because love means building oneness.”

Photos from day 4:

Entering the Holy Land through the back door

TEL AVIV — The African migrants of this Israeli city have recently been in the news, but they are not that visible to most tourists. The migrants live in the poorer, out-of-the-way precincts of Tel Aviv, near the Central Bus Station, far from the luxury hotels that line the Mediterranean beaches.

But since we have come not as tourists but as journalists, the migrants and their churches were our first stop after landing at Ben Gurion Airport. Professor Yarden told us that we were deliberately entering the country “through the back door.”

And so, we found ourselves at the Grace Covenant Gospel Church with a preacher from Ghana, Pastor Solomon, who ministers to the migrants. His is one of more than a dozen churches in the area around the bus station. Pastor Solomon has a kind face, bright eyes and hair that’s just beginning to gray.

Many of these migrants – from such places as Ivory Coast, Cameroon, South Africa, Congo and Ghana – have endured extreme hardships along the way and are at high risk for homelessness and drug addiction. “Sometimes you walk around and you see people just going crazy,” Solomon said, as he extended his hand towards the window behind us. “For them, this is the end of their rope.”

So Solomon offers three months of temporary shelter at the church, which occupies the fifth floor of a run-down tenement building in one of Tel Aviv’s poorer neighborhoods. “Our purpose is to give them hope,” he told us. “They are very injured when they get here.” His church also provides free food on Saturdays. Many of the African migrants living in the Middle East are men who’ve left their families in their home countries. So the church becomes their family.

“This is the only country in the Middle East where we can freely express our religion,” he said.

But not all are in the country legally and sometimes parishioners get arrested and deported. Whenever Solomon hears of an arrest, the congregation bands together to raise funds to hire a lawyer. But sometimes it is too late and the parishioner has already been deported.

African migrants have been coming to Israel in large number since the 1990s. After the government recently moved to expel many of them, there have been protests by both the migrants and their Israeli supporters against such deportations. One of us asked Solomon if his group ever participated in these. “We try to stay away from politics,” he said. “We are only here to serve the Lord.”

Solomon’s church was our third stop after the bus picked us up from Ben Gurion Airport this morning. After meeting Professor Goldman and Yarden, we went to Levinsky Park, which is a central meeting area for many of the African asylum seekers now in Israel. There we met Lisa Richlen, a Ph.D. student who briefed us on the history and statistics of migrants and asylum seekers in the country. She pointed out there is a high rate of drug use and prostitution in south Tel Aviv, where many of the most marginalized communities reside. “Natali Kingdom of Pork” declared the sign on a restaurant opposite the park. In a country made up of mostly Jews and Muslims, the sign proclaimed the unique nature of this district.

But pork wasn’t on the menu for us today. And rather than falafel or pita for lunch, we enjoyed the traditional African food of that district. We were greeted warmly inside by several African men who brought out platters of injera bread, beef, fried whole fish, beans, rice and okra. The proprietors were Jacob, a Muslim man from Darfour, and Sbhat, a younger Christian man from Eritrea. When we inquired about their interfaith business venture, both men laughed joyfully. “Jacob, he is like my father!” Sbhat said.

The delicious food on top of the jet lag made weary travelers of us all. We boarded the bus to what Goldman called “the front door of Israel,” the beachfront area of luxury hotels, embassies and art galleries. When we got back to the hotel, many of us strolled down to the beach to watch a beautiful sunset over the Mediterranean. Then we had a relaxed dinner and were joined by Covering Religion alumna Yardena Schwartz, CJS ’11.

On our first day in Israel, we barely met any Israelis or Jews or Arabs or Muslims. We followed one of the biggest news stories coming out of Israel by spending the day with African migrants. We’ve got the rest of the week to explore the others.

Photos from day 1:

To kiss a cloud of witnesses: Icons on the Lower East Side

NEW YORK — The first thing Maggie Downham does when she enters the inner sanctuary of the Orthodox Cathedral of the Holy Virgin Protection is kiss the icons.

Encased in a simple wooden frame on a pillar directly in front of the iconostasis, the wall separating the nave from the altar, is the icon of the day.

Downham stands before the small table propping up the image and makes the sign of the cross. Three fingers to the forehead, brought down to the stomach, taken over to the right shoulder and then to the left. She bows with her waist, her right hand open and touches the carpeted floor. Rising back to her upward position, she gently touches the contours of the icon and kisses first the feet and then the hands of the subject.

“The icon represents the presence of the sainthood, of a cloud of witnesses,” she said.

Icons can vary in length – the two-dimensional paintings plastered onto the iconostasis stretch upwards of several feet – but this one is the size of a framed family photo. It does contain a family of sorts. Beneath the glass, with the light of the surrounding candles flickering off its golden-hued glint, are dozens upon dozens of figures with haloes. In the center is a Russian Orthodox cross with its three crossbeams, and the background is filled with the domes of the Cathedral of the Dormition in Moscow. Its title: “Russian martyrs of the Soviet era.”

Once Downham has finished, she drifts off to the outer reaches of the church, repeating her metania, the series of prostration described above, before kissing other icons.

“We have a personal devotion to particular saints,” she said. “I try to center myself in front of the Virgin. But as I walk around, I go to whatever icon I feel connected with.”

The veneration of icons is considered by Eastern Orthodox Christians as a form of prayer and a conduit to deeper forms of spiritual reality.

“When worshippers pray in front of an icon, fundamentally they are looking at a mirror of themselves because we all share in the image of Christ,” said Richard Schneider, professor of iconology at St. Vladimir’s Seminary in Yonkers.

Icons have been central to the Christian imagination since at least the third century C.E. Yet throughout the early centuries of Christianity, there was constant tension between the distinction of venerating an icon or actually worshipping it.

“We don’t worship icons. They’re representations, like sermons. They open up to us understanding of the mystery. Because you also arrange them in the church, that order reveals a theology and a point about time,” Schneider said.

The icon of each day is pegged to the Orthodox liturgical calendar which typically celebrates the feast days of different saints. This cycle of change is contrasted with the plastered icons on the iconostasis, images which remain unchanging and eternal.

For Juliana Federoff, icons act as reminders.

“Icons are the connecting point between my worship on the weekend in the church and during the week at home. In both places I’m surrounded by them, and they help me understand life itself as worship to God.”

Even though Downham tends to venerate the icons near the beginning of the service, many will wander towards the images during other parts of the service.

This is because behavior at Orthodox services is much less scripted. “It’s strangely loose. It’s very respectful, but it doesn’t have a rigidity to it,” Schneider said.

Given the central role of icons in Orthodox worship – of how the images are touched, kissed, nudged, and felt – there aren’t many from Byzantine times and most in circulation were created in the 19th and 20th centuries.

But Schneider is okay with the predicament.

“There’s a lot of competition between churches and museums about who gets to keep the icons. The curators say they’ll get ruined, they’re kissed all the time and candles are burning. But icons are like people. They’re born, they flourish, and they die. Just like people.”

Heart and hand in Coptic Queens

NEW YORK — Outside, it was a quiet and nearly frigid Saturday morning in Queens – distinguished only, and only maybe, by being the day before the Super Bowl. But inside Ridgewood’s 606 Woodward Avenue, where the St. Mary & St. Antonios Coptic Orthodox Church sits stalwart but muted in monochrome brick, it was the holy 26th day of the month of Tubah.

A monitor hanging above the pews projected that date along with split-screen transcriptions of the assigned liturgical texts: English on the left, Arabic on the right. From a sidelined podium, adolescent boys read quickly, without looking up, through passages from Hebrews and Peter. “If you endure chastening,” read the first boy, “God deals with you as with sons.” His muffled delivery suggested a plea for that eventual payoff.

The readings shifted from forced to fluid as Abouna Eshak chanted the primary section, Matthew 4:23—5:16, in Arabic from the central podium. Altar boys flanked him with candles, and the words floated out from behind a literal, pungent fog. They graced the ears as burning incense tickled the nostrils, lending the words some kind of multidimensional body.

In these short verses, Jesus travels throughout Galilee teaching in synagogues and healing the sick, drawing and healing crowds of “those suffering severe pain, the demon-possessed, those having seizures, and the paralyzed” from as far away as Jordan. In time, the crowds become overwhelming and Jesus resolves to address them from a mountainside, where he recites the eight Beatitudes from his famous Sermon on the Mount. The selection includes blessings for “those who mourn, for they will be comforted,” and for “the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.”

Abouna Eshak delivered his sermon in alternating Arabic and English. These verses, he said, are key in separating Christ from the Jews who preceded him. Those earlier Jews, said the Abouna, only valued deeds – not what was in “the hearts of the people.” Jesus, in other words, demonstrated an innovative concern for thought, or faith, or words – his eyes saw beyond mere actions. The words that constitute the eight Beatitudes come, Abouna said, “from all the branches of life.”

They are themselves a life force, he continued, compelling their continued recitation all these 2,000 years later. To drive the point home, Abouna worked his way up to reciting the sixth Beatitude: “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God.”

However frequently or not Abouna Eshak hits this theme, it made sense in a sanctuary that surrounds its congregants with words from the Bible: plaques above the left pews, right pews, and entrance announce verses from Isaiah 56:7, Genesis 28:16 and Genesis 28:17.

But his celebration of words felt detached from his rather soporific, rote delivery. Throughout most of the service, the congregation was a mix of standers and sitters. During the sermon, however, everyone sat and some seemed disengaged: texting, entering and exiting, and looking down short of bowing their heads in prayer. The words floated passively throughout the room and seemed to be over almost as soon as they had started. The sermon induced a palpable loss of energy between the moments that both preceded and followed it: the theatrical ritual of chanting the verses through a haze of incense and – ironically enough –the performative, action-based symbolic exchange between neighbors in the pews.

I was hastily – and apparently quite visibly – completing my notes on Abouna’s sermon when the three men closest to me turned to swipe their hands with mine. One by one, we stuck our hands out horizontally towards one another’s, alternated them until they were clasped, and slid them slowly apart. Noting my ignorance, one of the men explained that the gesture means “we ask forgiveness from each other.”

Abouna was not the only teacher present, and words were not the only tools of faith in use.