You Can't See Any Such Thing

You Can’t See Any Such Thing An Interactive Fiction by Matt Sheridan Smith

In spite of the unprecedented proliferation and circulation of images today, power is still largely consolidated in and through writing, whether via code that creates a body of intellectual property, legislation that protects it, hacking that subverts it, or news that narrates it. Interactive fiction is the literary descendent of text-adventure games, which offer players no visual interface at all: just textual descriptions and a command line for inputs. The “game” at hand is actually produced by a three-way symbiotic writing between player, author, and interpreter (i.e., the software environment in which the game is played). The player becomes a cowriter, but all possible moves are already in the script. The player may have blithely interacted with an object in the text, have “smelled” something and read on as it “answered” with a response. But should she attempt anything unorthodox, the player will receive the dreaded error message: You can’t see any such thing. The game is “intelligent” only insofar as it has been, on the level of code, described to itself. You can’t go that way. In these moments, the player encounters the limit of the game’s coded world, a discovery that also triggers the end of the player’s suspension of disbelief. Paradoxically, only in moments at which the player tries to move beyond the game’s internal knowledge does the game manifest subjectivity: That’s not a verb I recognize.

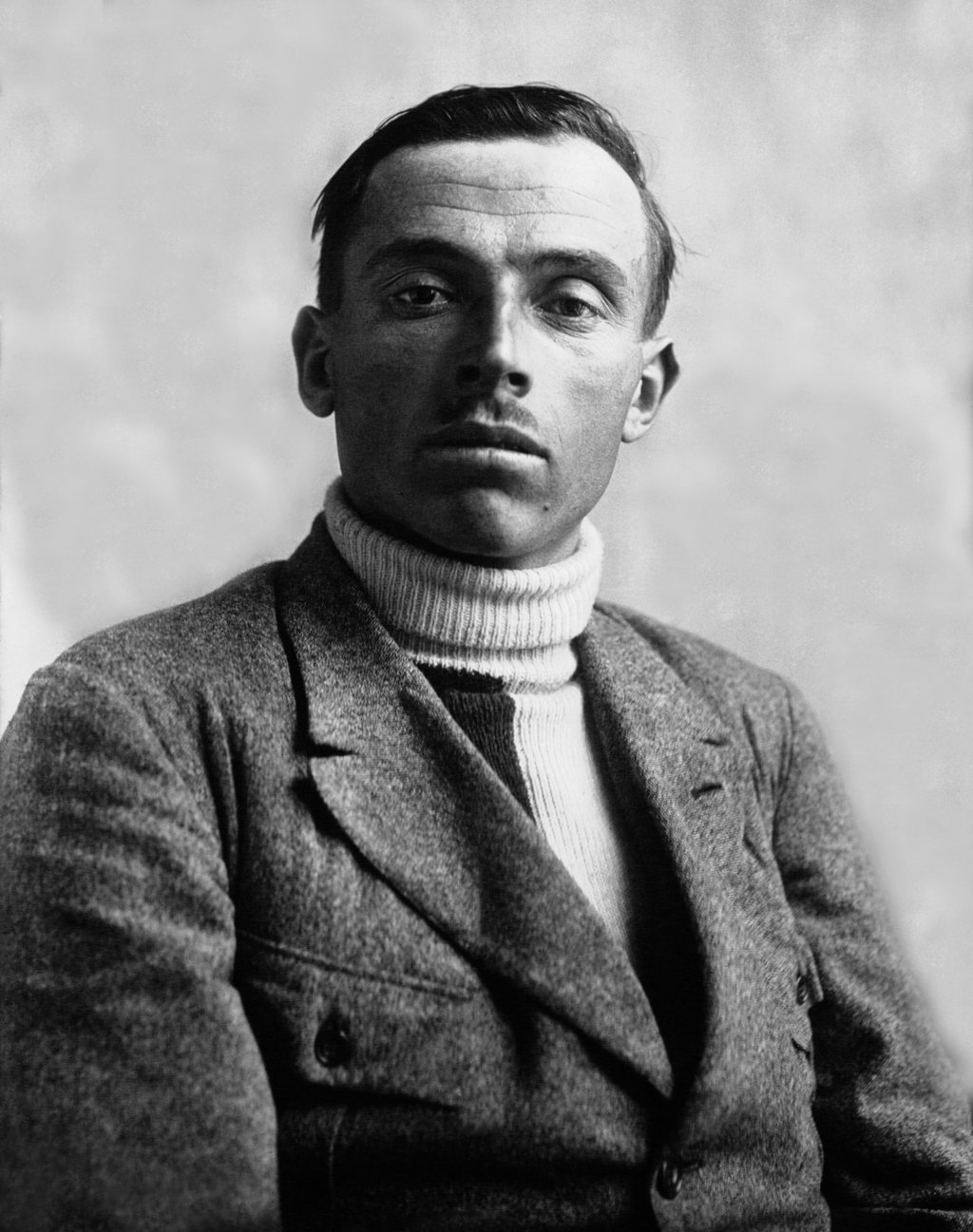

You Can’t See Any Such Thing has four characters: Madame Clicquot,  a widow; Douglas Bader,

a widow; Douglas Bader,  a pilot; Ottavio Bottecchia,

a pilot; Ottavio Bottecchia,  a cyclist; and a mysterious actress named Katie,

a cyclist; and a mysterious actress named Katie,  who is capable of inhabiting the other figures. Katie, like the player, has fallen victim to a split in identity: She is both a player in and a player of the world at hand. These characters first appeared in a 2011 exhibition in Geneva called “Tell me the truth—am I still in the game?” and have been major preoccupations ever since. Along with artworks that occupied the space, at the center of the gallery was a computer with a playable interactive-fiction game, a predecessor to You Can’t See Any Such Thing. This 2011 game was a sort of description machine for the works in the gallery, a portal into a fuller narrative concerning the characters in the exhibition. The game served as an interface by means of which players might access information that would otherwise remain encrypted in the muteness of the display. This double inscription of scene and screen, writing and playing, reading and seeing, made the game both a replication and a deformation of a visit to the exhibition.

The new game, You Can’t See Any Such Thing, frees itself entirely from the exhibition as referent or starting point. Instead, the player begins in a flattened time-space, where historically distinct eras are somehow unified through the copresence of four characters. Each character inhabits a different sensorial realm. Each navigates by means of a single sense, which provides a trigger for memory as well as fiction. The pilot has crashed

who is capable of inhabiting the other figures. Katie, like the player, has fallen victim to a split in identity: She is both a player in and a player of the world at hand. These characters first appeared in a 2011 exhibition in Geneva called “Tell me the truth—am I still in the game?” and have been major preoccupations ever since. Along with artworks that occupied the space, at the center of the gallery was a computer with a playable interactive-fiction game, a predecessor to You Can’t See Any Such Thing. This 2011 game was a sort of description machine for the works in the gallery, a portal into a fuller narrative concerning the characters in the exhibition. The game served as an interface by means of which players might access information that would otherwise remain encrypted in the muteness of the display. This double inscription of scene and screen, writing and playing, reading and seeing, made the game both a replication and a deformation of a visit to the exhibition.

The new game, You Can’t See Any Such Thing, frees itself entirely from the exhibition as referent or starting point. Instead, the player begins in a flattened time-space, where historically distinct eras are somehow unified through the copresence of four characters. Each character inhabits a different sensorial realm. Each navigates by means of a single sense, which provides a trigger for memory as well as fiction. The pilot has crashed  and must claw his way out of the wreck, touching hot metal, sticky grease, coarse wool. The widow has only smell. We enter her boudoir,

and must claw his way out of the wreck, touching hot metal, sticky grease, coarse wool. The widow has only smell. We enter her boudoir,  where she sits at a vanity, perfumes before her. Smell one, and a flashback is triggered. As Katie, the player must learn to “listen to” three distinct forms of silence

where she sits at a vanity, perfumes before her. Smell one, and a flashback is triggered. As Katie, the player must learn to “listen to” three distinct forms of silence  . The cyclist is already dead when the player arrives, but a psychic will help the player “see” into the scene at hand

. The cyclist is already dead when the player arrives, but a psychic will help the player “see” into the scene at hand  . In each case, sensation stands in for reality.

If you play the game “right,” you will proceed deeper into each character’s world. Key items are bolded. You follow the instructions (touch, smell, see, listen) and are rewarded with a series of scenes that seem like accurate memories of the characters’ lives, but are actually, without exception, small works of fiction. If you misplay and produce a parser error, after the standard message the game will identify a plot hole. This message is intended to distract you from the fact that you have uncovered not a hole in the narrative, but a hole in the game’s own constructed understanding. Here the game provides a short passage in a voice entirely distinct from the voice you’ve become accustomed to in playing the game correctly. This voice speaks in facts.

Thus, playing the game correctly pushes you further into the realm of fiction, while playing it incorrectly, making mistakes, yields more and more truth. Error generates fact. These facts, while specific to the character you are currently playing, rotate at random, so you may not remember whether or not you have seen them before. The scenes are short and disconnected, and the more you read the more plot holes are revealed. With each scene’s excavation, the story’s whole is buried deeper. In the pilot’s crash scene, for example, he sees fields as he goes down. Meanwhile, in a scene with the widow, as we flash back to a memory of being a fourteen-year-old girl playing in the fields, a plane crashes—anachronistically and impossibly—in the background. Interactive fiction resembles a riddle; we reach the point of greatest fascination at the very moment at which the riddle, or fiction, threatens to undo itself. We are happiest at the limits of the game.

. In each case, sensation stands in for reality.

If you play the game “right,” you will proceed deeper into each character’s world. Key items are bolded. You follow the instructions (touch, smell, see, listen) and are rewarded with a series of scenes that seem like accurate memories of the characters’ lives, but are actually, without exception, small works of fiction. If you misplay and produce a parser error, after the standard message the game will identify a plot hole. This message is intended to distract you from the fact that you have uncovered not a hole in the narrative, but a hole in the game’s own constructed understanding. Here the game provides a short passage in a voice entirely distinct from the voice you’ve become accustomed to in playing the game correctly. This voice speaks in facts.

Thus, playing the game correctly pushes you further into the realm of fiction, while playing it incorrectly, making mistakes, yields more and more truth. Error generates fact. These facts, while specific to the character you are currently playing, rotate at random, so you may not remember whether or not you have seen them before. The scenes are short and disconnected, and the more you read the more plot holes are revealed. With each scene’s excavation, the story’s whole is buried deeper. In the pilot’s crash scene, for example, he sees fields as he goes down. Meanwhile, in a scene with the widow, as we flash back to a memory of being a fourteen-year-old girl playing in the fields, a plane crashes—anachronistically and impossibly—in the background. Interactive fiction resembles a riddle; we reach the point of greatest fascination at the very moment at which the riddle, or fiction, threatens to undo itself. We are happiest at the limits of the game.

a widow; Douglas Bader,

a widow; Douglas Bader,  a pilot; Ottavio Bottecchia,

a pilot; Ottavio Bottecchia,  a cyclist; and a mysterious actress named Katie,

a cyclist; and a mysterious actress named Katie,  who is capable of inhabiting the other figures. Katie, like the player, has fallen victim to a split in identity: She is both a player in and a player of the world at hand. These characters first appeared in a 2011 exhibition in Geneva called “Tell me the truth—am I still in the game?” and have been major preoccupations ever since. Along with artworks that occupied the space, at the center of the gallery was a computer with a playable interactive-fiction game, a predecessor to You Can’t See Any Such Thing. This 2011 game was a sort of description machine for the works in the gallery, a portal into a fuller narrative concerning the characters in the exhibition. The game served as an interface by means of which players might access information that would otherwise remain encrypted in the muteness of the display. This double inscription of scene and screen, writing and playing, reading and seeing, made the game both a replication and a deformation of a visit to the exhibition.

The new game, You Can’t See Any Such Thing, frees itself entirely from the exhibition as referent or starting point. Instead, the player begins in a flattened time-space, where historically distinct eras are somehow unified through the copresence of four characters. Each character inhabits a different sensorial realm. Each navigates by means of a single sense, which provides a trigger for memory as well as fiction. The pilot has crashed

who is capable of inhabiting the other figures. Katie, like the player, has fallen victim to a split in identity: She is both a player in and a player of the world at hand. These characters first appeared in a 2011 exhibition in Geneva called “Tell me the truth—am I still in the game?” and have been major preoccupations ever since. Along with artworks that occupied the space, at the center of the gallery was a computer with a playable interactive-fiction game, a predecessor to You Can’t See Any Such Thing. This 2011 game was a sort of description machine for the works in the gallery, a portal into a fuller narrative concerning the characters in the exhibition. The game served as an interface by means of which players might access information that would otherwise remain encrypted in the muteness of the display. This double inscription of scene and screen, writing and playing, reading and seeing, made the game both a replication and a deformation of a visit to the exhibition.

The new game, You Can’t See Any Such Thing, frees itself entirely from the exhibition as referent or starting point. Instead, the player begins in a flattened time-space, where historically distinct eras are somehow unified through the copresence of four characters. Each character inhabits a different sensorial realm. Each navigates by means of a single sense, which provides a trigger for memory as well as fiction. The pilot has crashed  and must claw his way out of the wreck, touching hot metal, sticky grease, coarse wool. The widow has only smell. We enter her boudoir,

and must claw his way out of the wreck, touching hot metal, sticky grease, coarse wool. The widow has only smell. We enter her boudoir,  where she sits at a vanity, perfumes before her. Smell one, and a flashback is triggered. As Katie, the player must learn to “listen to” three distinct forms of silence

where she sits at a vanity, perfumes before her. Smell one, and a flashback is triggered. As Katie, the player must learn to “listen to” three distinct forms of silence  . The cyclist is already dead when the player arrives, but a psychic will help the player “see” into the scene at hand

. The cyclist is already dead when the player arrives, but a psychic will help the player “see” into the scene at hand  . In each case, sensation stands in for reality.

If you play the game “right,” you will proceed deeper into each character’s world. Key items are bolded. You follow the instructions (touch, smell, see, listen) and are rewarded with a series of scenes that seem like accurate memories of the characters’ lives, but are actually, without exception, small works of fiction. If you misplay and produce a parser error, after the standard message the game will identify a plot hole. This message is intended to distract you from the fact that you have uncovered not a hole in the narrative, but a hole in the game’s own constructed understanding. Here the game provides a short passage in a voice entirely distinct from the voice you’ve become accustomed to in playing the game correctly. This voice speaks in facts.

Thus, playing the game correctly pushes you further into the realm of fiction, while playing it incorrectly, making mistakes, yields more and more truth. Error generates fact. These facts, while specific to the character you are currently playing, rotate at random, so you may not remember whether or not you have seen them before. The scenes are short and disconnected, and the more you read the more plot holes are revealed. With each scene’s excavation, the story’s whole is buried deeper. In the pilot’s crash scene, for example, he sees fields as he goes down. Meanwhile, in a scene with the widow, as we flash back to a memory of being a fourteen-year-old girl playing in the fields, a plane crashes—anachronistically and impossibly—in the background. Interactive fiction resembles a riddle; we reach the point of greatest fascination at the very moment at which the riddle, or fiction, threatens to undo itself. We are happiest at the limits of the game.

. In each case, sensation stands in for reality.

If you play the game “right,” you will proceed deeper into each character’s world. Key items are bolded. You follow the instructions (touch, smell, see, listen) and are rewarded with a series of scenes that seem like accurate memories of the characters’ lives, but are actually, without exception, small works of fiction. If you misplay and produce a parser error, after the standard message the game will identify a plot hole. This message is intended to distract you from the fact that you have uncovered not a hole in the narrative, but a hole in the game’s own constructed understanding. Here the game provides a short passage in a voice entirely distinct from the voice you’ve become accustomed to in playing the game correctly. This voice speaks in facts.

Thus, playing the game correctly pushes you further into the realm of fiction, while playing it incorrectly, making mistakes, yields more and more truth. Error generates fact. These facts, while specific to the character you are currently playing, rotate at random, so you may not remember whether or not you have seen them before. The scenes are short and disconnected, and the more you read the more plot holes are revealed. With each scene’s excavation, the story’s whole is buried deeper. In the pilot’s crash scene, for example, he sees fields as he goes down. Meanwhile, in a scene with the widow, as we flash back to a memory of being a fourteen-year-old girl playing in the fields, a plane crashes—anachronistically and impossibly—in the background. Interactive fiction resembles a riddle; we reach the point of greatest fascination at the very moment at which the riddle, or fiction, threatens to undo itself. We are happiest at the limits of the game.