Going Further 17.2: A Flat Universe

The Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) is the relic radiation from the hot, dense, early phase of the Universe, which has been stretched by the expansion of space. Tiny temperature variations measured in the CMB provide the seeds for the formation of the large scale structure that we observe in the Universe today. By precisely measuring the sizes and distribution of these fluctuations, astronomers determined that the Universe was flat, i.e. that the matter-energy density of the Universe was equal to the critical density.

In Euclidean geometry (the geometry of the Pythagorean theorem) parallel lines never intersect, angles of a triangle add up to 180 degrees, straight lines are the shortest distance between two points, and standard trigonometry applies. Space with this type of geometry is often referred to as flat. Flat in this case does not necessarily mean two-dimensional like the surface of a table or flat like a pancake, it just means that normal Euclidean geometry applies and that there is no overall curvature. A flat space in this sense can have three or even more dimensions.

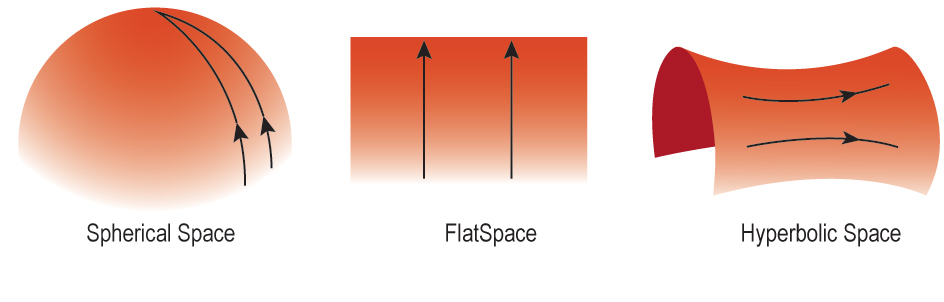

In a spherical geometry, such as the surface of Earth, parallel lines converge and the angles of a triangle can add up to more than 180 degrees. A space with a spherical geometry is said to have a positive curvature. Another curved geometry is a hyperbolic geometry, in which space is saddle shaped. In such a space parallel lines diverge and the angles of a triangle add up to less than 180 degrees. This type of space is said to have negative curvature. These possibilities are shown in Figure B.17.1.

Credit: NASA/SSU/Aurore Simonnet

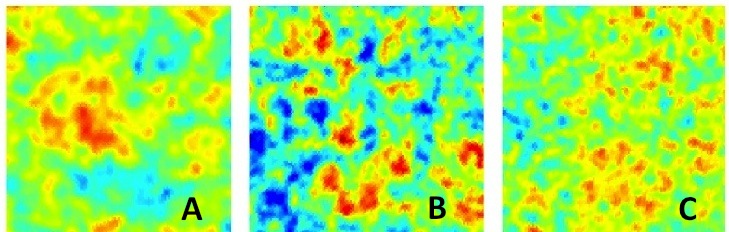

Objects in spacetime appear different sizes depending on the curvature that is measured. If space is positively curved (spherical), an object will appear larger than if space is flat. If space is negatively curved (hyperbolic), an object will appear smaller than if space is flat. This also applies to the size of the variations that are measured in the CMB as shown in Figure B.17.2.

Credit: BOOMERANG Collaboration.

The CMB fluctuations that are observed are an excellent match for Map B in this figure. This indicates that the Universe has a flat geometry: Ω = 1. Other measurements support this claim.