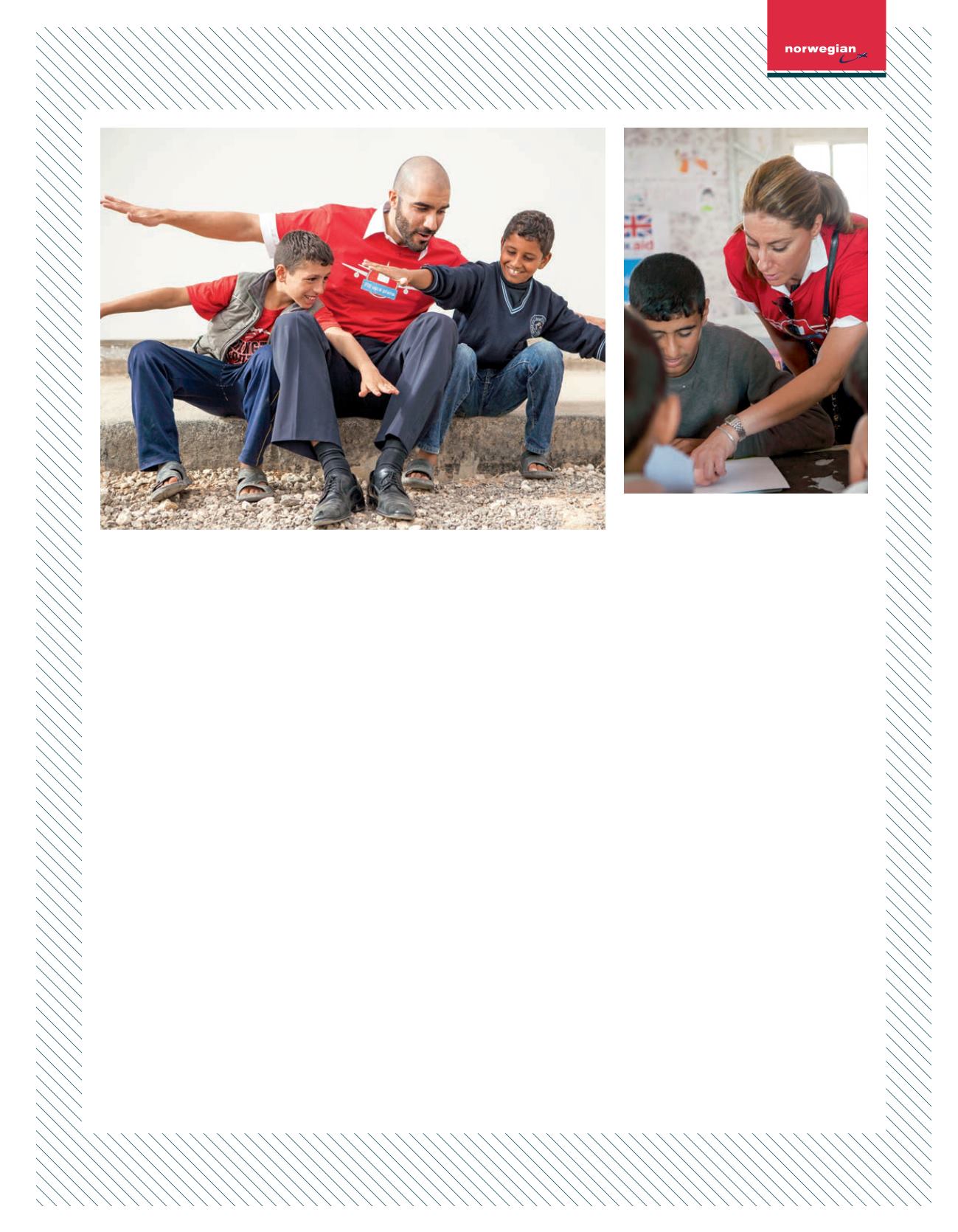

Norwegian’sChadiHanaataMakani school;andone-

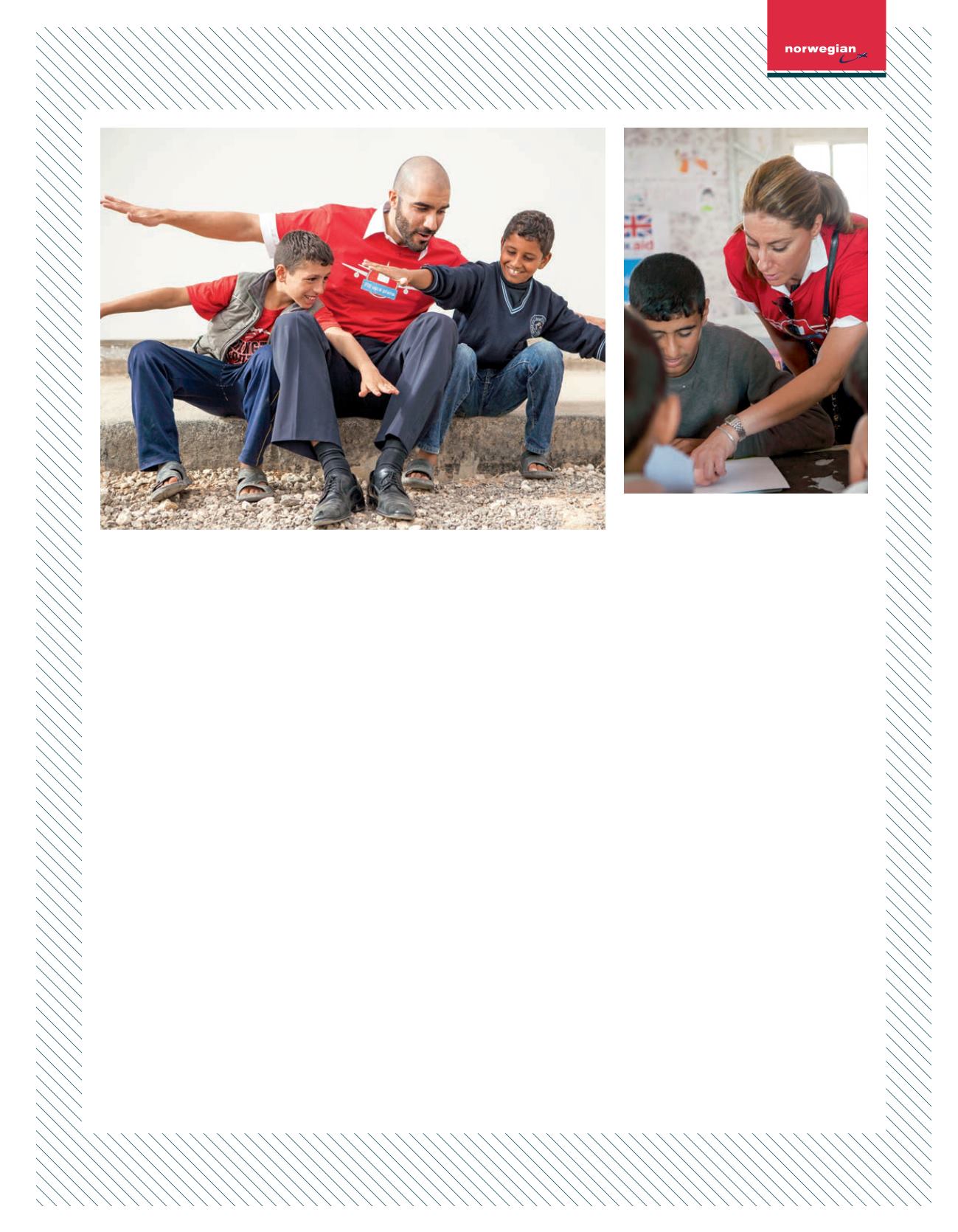

timeLebaneserefugeeRaniaHidohelpswithaclass

I

t’s themonotony that’s

hard tobear. From a

viewpoint high above,

all youcan see are

dust-coatedboxes

stretching to theedges of vision.

Driving through it, the space is only

brokenby amain road– known

ironically as theChamps-Élysées for its

long lineof tarpaulin-draped shacks,

piledwithmounds of vegetables,

tinned food anddusty shoes.

This is Za’atari. Founded in2012,

the refugeecamp is peopledby those

whohaveescaped the violence across

the Jordanianborder in Syria. It’s

nowhome to about 80,000people

– aroundhalf ofwhom areunder

18. As only a small proportionof

thesechildrenhas access to formal

education, there’s a very real worry

that thesedisplaced youngsterswill

become a lost generation.

UNICEF andNorwegian’s Fill Up a

Planemissionwas devised for these

youngpeople.With the aidof UNICEF

andpassengers, who raisedoverNOK

2million, the airlinewas able to stuff

oneof its 737planeswithmore than 13

tonnes of educational supplies headed

for theZa’atari camp.

Alsoon the flight, on2November,

areUNICEF andNorwegianMinistry

representatives, alongside 10

Norwegian staff, including the airline’s

CEOBjørnKjos. Among them are

pilots andcabincrewwhohavebeen

nominatedby their colleagues. Rania

Hido is oneof the lucky ones.

“I was delighted tobechosen,” she

says. “Especially because I knowwhat

it’s like tobe thosechildren.”Hidowas

just two years oldwhen she fled the

civil war in Lebanon toNorway. “I felt a

bit like thiswas payback.”

On themorning after arrival, she and

her colleagues set off to thecamp to

distribute someof the supplies to a

school there. “I didn’t knowwhatwe’d

find. I expectedmore sadness in the

eyes of thechildren, becauseof the

desperate situation they are in–but

theywere sohappy to seeus.”

In amakeshift school building, with

missingpieces of ceiling, the group

offloads someof the school supplies,

which are greetedwith adegreeof

joy thatwouldbeunusual frommany

children in theWest.When thecrew

asks a groupof teenage girls their

plans for the future, all of them say

they hope to go touniversity.

Sadly, this ambitionwill bebeyond

the reachofmany. Althoughmore than

143,000 refugeechildrenhavebeen

enrolled in theJordanian school system

this year –a 10per cent increaseon

2014–many youngpeoplehaveno

access toeducationor training. Tohelp,

UNICEFhas set up severalMakani (My

Space) centres,whichact as informal

schools. Thesecentres giveunder-18s

what is termed “psychosocial support”,

in the formof socialisation, art, sport

andmusic therapy.

“Coming fromwar, thereare

sometimesdifficulties gettingchildren

to school,”explainsReemBatarseh,

a local UNICEF representative. “If

they’renot at school thenparentsmay

want them towork, or getmarried. If

theycan’t beat school, at least they

cancomehere, learn, run…doall the

activitiesof childhood. It’s so important

theyhaveachance to just beachild.”

On the team’s visit tooneof these

Makanis, outside thecamp, a groupof

boys aged 10-12 are learning about the

UN’s rights of the child. Although

»

“It’s so important theyhave

achance to justbeachild”

n

/091