|

Below is Chapter 1 of the John Locke Foundation's recently published book, |

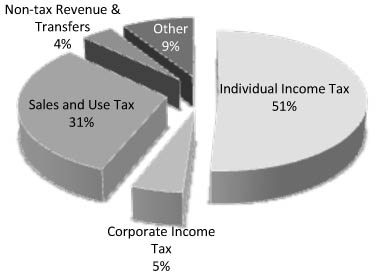

The Time Is Right For Sweeping Tax ReformBy Roy Cordato In a free society, one that respects individual liberty and freedom of choice, taxation has one and only one purpose, to raise the revenues necessary to fund the government. And this should be done while minimizing the damage that the tax system does to both the economy and individual freedom of choice. The tax system in North Carolina has strayed dramatically from this fundamental idea. The state relies on a tax code that discourages some choices and businesses, often in the name of saving the environment or protecting people's health, while subsidizing others, typically in the name of economic development. The task of this chapter is to discuss how all this can be changed through tax reform that is informed by sound economic analysis and sound principles of democracy and good government. Where Are the Problems?The problems are everywhere you look. North Carolina relies primarily for its revenues on two different taxes — the personal income tax, which accounts for 51 percent of revenues, and the sales tax, which makes up 31 percent of revenues. The third-largest revenue raiser is the corporate income tax, at a much smaller 5 percent of total revenue. Added to this mix is a host of less significant taxes, at least in terms of total revenues generated, which includes estate taxes, excise taxes on items like alcohol and cigarettes, and business franchise taxes. Both the income tax and the sales tax need extensive reform in order to come into compliance with sound principles of taxation, while the the corporate income tax really has no place as part of a tax system in a free and democratic society. Even a cursory look at the system of taxes in North Carolina reveals that it has been constructed in a completely ad hoc manner with little if any attention to the basic principles of either a free society or efficient taxation.

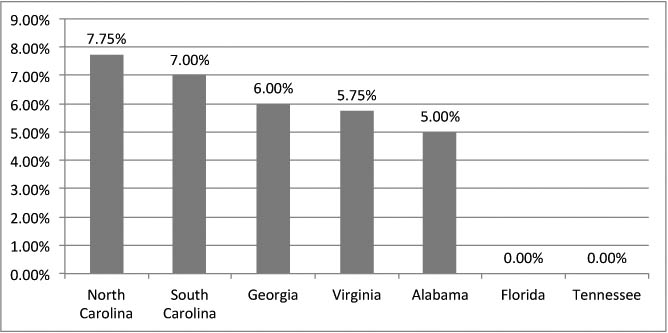

The principles to which I refer can be subsumed under two broad categories. The first is economic efficiency, which focuses on what economists call "neutrality," or the idea that a tax system should not penalize some activities and reward others. It should, to the extent possible, be neutral with respect to people's decision making. For an economist, a market is efficient when it accurately reflects actual conditions of supply and demand, that is consumer preferences and resource scarcities. So a neutral tax system is one that interferes with this as little as possible. The second is transparency, which is important because, in a democracy, people should have a clear idea of what government is costing them. Taxes are the most obvious indicator of this. If the amount of the taxes being paid is hidden from the people who are actually paying them, decision making at the ballot box is impaired. A transparent tax system is a prerequisite for an informed citizenry. North Carolina's most important revenue raisers — the income, sales, and corporate income taxes — violate both of these principles. In what follows, I will examine each of these taxes and their problems in detail. I will also assess other, less consequential taxes that plague and ultimately corrupt our system of revenue-raising. Ultimately this chapter will examine and evaluate alternatives for reform of the system. North Carolina's Income TaxSince its inception in 1921, the North Carolina income tax has had a graduated, or progressive, rate structure. (The desirability of this will be discussed below.) What this means is that, as incomes increase, specified increments to income are taxed at increasingly higher rates. For example, in 1924 North Carolina had a relatively straightforward system. With each increment in taxable income (after deductions) of $2,500 up to $10,000, the rate was increased by 0.75 percent. So the first $2,500 was taxed at 1.25 percent. If a person had $5,000 in taxable income, the first $2,500 was taxed at 1.25 percent and the second was taxed at 2.0 percent. This was continued up to a taxable income of $10,000. Income above $10,000 was taxed at 4.5 percent.1 The term "marginal tax rate" refers to the rate that is being paid on the last increment of income. So, in the 1924 example, a person earning $10,000 would face a "marginal rate" of 3.5 percent on the last $2,500 increment between $7,500 and $10,000, while a person earning $14,000 would face a "marginal rate" of 4.5 percent on the $4,000 above $10,000. As an aside, $10,000 in 1924 would be equivalent to an income of over $126,000 in 2010 dollars, which would be taxed at a marginal rate of 7.75 percent today. It should also be noted that, while rates at the federal level have trended downward over the last 40 years, except for the expiration of a statutorily temporary increase in the rates in 2007, there has never been a lowering of the structure of marginal rates for the entire history of the North Carolina income tax. Every change since 1924 that was not instituted specifically as a temporary measure to deal with a transient problem has resulted in a rate increase. Most recently in 2001 a temporary top rate of 8.25 percent was instituted for two years and extended for an additional two years to deal with a budget deficit caused by excessive spending in the 1990s. Penalizing productivity and growthThe current rate structure goes from a bottom rate of 6 percent (1.5 points higher than the top rate when the tax was put in place in 1921) to a top rate of 7.75 percent. Except where distinctions are made in the federal code, such as IRAs and other specially designated savings accounts, the North Carolina income tax system makes no distinction between different kinds of income. For example, all returns to saving and investment, such as capital gains, interest, and dividends, are considered to be ordinary income and are taxed at the same rates as other forms of income. This is partly at odds with the federal system, which taxes capital gains, and with recent changes dividends, at lower rates. I will argue below that by taxing returns to investment and saving, North Carolina introduces double taxation into its tax code and creates a bias against investment activities. With some notable exceptions, primarily the taxation of capital gains and now dividends, North Carolina's income tax is modeled after the federal income tax. This means that it defines "taxable income" in the same way and, by and large, "piggy-backs" on the federal tax code when determining what are and are not deductible expenses. Because of this, our state income tax system suffers the same problems as the federal system in that it is dramatically biased against work effort relative to leisure and saving and investment relative to consumption spending. These biases, which violate the neutrality principle, stifle both economic growth and job creation. The economic biases, or "non-neutralities," created by the North Carolina income tax system are generated by both its rate structure and the way it defines taxable income, i.e., its base. As noted previously, North Carolina has a rather steeply progressive tax rate structure that biases against work effort and productivity, and the tax base is defined in such a way that it double, and in some cases triple, taxes the returns on saving and investment. In the academic literature on the economics of taxation, there is a well-known saying that "people aren't taxed, activities are." The technical way of saying this is that nearly all taxes have an "excise effect." Taxes are generated by siphoning off revenues from one form or another of economic activity. Because taxation reduces the rewards or increases the costs associated with these activities, it discourages them. For example, a tax on cigarettes discourages smoking, a tariff discourages the importation of foreign-made products, a tax on gasoline discourages gasoline consumption, etc. What often is not recognized is that the income tax also has an excise effect. It places a tax penalty on all income-generating activities — work effort, entrepreneurship, saving, and investment. These are the activities that generate economic growth, productivity and employment opportunities. The North Carolina income tax is no exception. When compared to income taxes of other states, its anti-productivity bias is particularly egregious. Taxing work effortThis tax penalty on productive activity is most easily demonstrated when analyzing how the income tax has an impact on work effort. People pursue economically productive activities because of the income that they generate. The greater the rewards to these activities, the more likely that they will be pursued. In any particular instance, when deciding how much they are willing to work, people will weigh the satisfaction that they expect to receive from doing other things (what we will generically call leisure) against the income that they would receive from pursuing the work-related activities. These kinds of decisions are made on a regular basis. When people are deciding to work overtime, to take a second job, or to go back to school to get higher degrees or additional training, they assess the additional income that can be gained from these additional efforts and weigh it against the other activities in their lives that they will have to give up. Income taxation distorts this value judgment in favor of leisure activities. It reduces the financial return to the work activity while leaving the inherently non-pecuniary rewards to leisure untouched. In the terminology of public finance, income taxation drives a "wedge" between the rewards to work effort and the rewards to non-work activities. The higher the tax rate, the greater the wedge, i.e., the greater the penalty against additional economic productivity, and the more distorting the tax. Here's an illustration. Imagine an income tax system imposing one flat rate of 100 percent with no deductions (i.e., both the marginal and average rate are 100 percent). It is obvious that people, at least for public record-keeping purposes, would put no effort into income-generating activity. As the tax rate fell from 100 percent, the wedge would be reduced and the mix of leisure and work activity would shift. At a tax rate of zero, the wedge would disappear. Given people's true needs and preferences, work effort and productivity would be maximized, and the efficient mix of work and leisure would occur. This mix is guided purely by the interaction of individual preferences and the wages that employers are willing to pay (driven by the value of output produced) as compensation for services rendered. North Carolina's income tax system enhances this tax penalty, both absolutely and relative to other states, in two different ways. Its income tax rates are high relative to the national average and are particularly high relative to other states in the Southeast with which we are economically most competitive. Not only is North Carolina's top marginal rate of 7.75 percent the highest among states in the region (see Figure 2), but our bottom rate of 6 percent is, except for South Carolina, equal to or higher than the top rate in all other Southeastern states. It should also be noted that Florida and Tennessee have no state income tax.

Adding to this anti-productivity bias is North Carolina's steeply progressive rate structure. That is, the marginal tax rate increases as incomes increase. A progressive rate penalizes increased productivity by taking a greater percentage of additions to people's income as they earn more. People climb the economic ladder, in terms of raises and job and career changes, by making themselves more productive. Progressive taxation punishes people for making productivity enhancing changes in their lives, adding an additional bias against economic growth and wealth creation. Penalizing saving, investment, and entrepreneurshipThe income tax penalty on savings, investment, and entrepreneurship is analogous to the penalty against work effort. It follows from the fact that the tax is biased against all income-generating activity, which, in a market economy, is the engine of economic growth and prosperity. The easiest way to see this is to first note that the broad choice facing an individual with a certain amount of after-tax income is either to spend that after-tax income or to save and invest it. Like the leisure/work choice discussed previously, the consumption/saving choice is distorted by the income tax. Under the typical income tax system, the returns to saving, such as interest, are taxed, while the rewards to consumption, which relate to personal satisfaction and are non-pecuniary, are not. The tax system, therefore, penalizes saving and investment by reducing the returns to those activities relative to consumption. An alternative and more useful way of viewing this bias, in terms of identifying approaches to tax reform, is by showing that income taxation, using the traditional terminology, "double taxes" saving relative to consumption. (This terminology is somewhat misleading. More accurately, the tax reduces the returns to saving twice, while reducing the returns to consumption just once.) This can be demonstrated with a simple example. Start with an individual who has $100 of pre-tax income. In the absence of taxation, this person has $100 available for either saving/investment or consumption (the purchase of goods and services). If the interest rate is a simple 10 percent per year, then the person can decide whether he prefers to spend $100 or save the $100 and have $110 available for spending a year from now. The decision will be based on his needs and desires and the needs and desires of those who depend on him. Now assume that the individual faces a 10 percent income tax. His $100 is reduced to $90. This reduces the amount available for consumption by 10 percent and, likewise, it reduces his returns to saving by 10 percent. If the $90 is saved, his interest income is reduced to $9. In the absence of further taxation his choice is between spending $90 now or waiting a year and having the opportunity to spend $99. But under an income tax, the returns to saving get hit again. The $9 in interest gets taxed by 10 percent also. The return to saving is reduced to $8.10. The tax reduces these returns twice: first, from $10 to $9 when the initial $100 is taxed and second, from $9 to $8.10 when the interest is taxed. The return from consumption is only reduced once, from the level of satisfaction that could be obtained with $100 to the level that could be obtained with $90. The tax on interest or other returns to investment, including the taxation of dividends and capital gains, biases the decision against saving, investment, entrepreneurship, and business expansion and in favor of consumption spending. If we apply North Carolina's top marginal rate and look at its actual impact on investment returns — including interest, dividends, and capital gains — we discover that, while reducing the rewards to current consumption by 7.75 percent, it reduces investment returns by about 15 percent. In other words, North Carolina has an implicit top marginal rate on saving and investment of almost double its statutory rate. By taxing saving and investment, North Carolina has a strong anti-productivity bias in its tax code, which stifles entrepreneurship and ultimately job creation. This anti-growth bias does not exist in states like Florida and Tennessee, which have no income tax. North Carolina's Sales Tax2North Carolina's sales tax, which applies to non-food products and no services, is the second largest revenue generator in the state's tax arsenal. It was instituted in July 1933. The story behind the tax is a familiar one. The new tax was set at 3 percent and, of course, was "temporary." It was set to expire in 1935.3 It should come as no surprise to anyone familiar with new revenue proposals in North Carolina that the original purpose of the tax was "to help fund education" during the lean years of the Great Depression when local property and income tax revenues were down. After several extensions of this "temporary" tax, it was finally made permanent after extending the expiration date to 1939.4 The rate stayed at 3 percent until 1991 when it was increased to 4 percent. Then in 2001 it was raised "temporarily" to 4.5 percent. Not surprisingly, given the history of the tax, when it was about to expire in 2003 it was extended to July 2005. The 4.5 percent rate was made permanent. In 2009 the rate was raised 1.25 percent, a penny of which was not permanent and was allowed to expire in 2011. While the rate currently stands at 4.75 percent, the total tax in most counties is between 7 and 8 percent due to local-option sales taxes. The exemption for food items not eaten on the premises began in 1996 but was eliminated in July 1997. This exemption has been instituted and rescinded many times over the 70 years that the tax has been in place. The most important problems with North Carolina's sales tax center around its base — what is and isn't subject to the tax. The "fix" for these problems, unlike the "fix" for the income tax to be addressed in the section that follows, is implicit in their identification. North Carolina's sales tax violates the neutrality principle by excluding some categories of purchases that should be included and including categories that sound principles of taxation suggest should be excluded. In other words, the sales tax base is too narrow in some areas and too broad in others. The reason for this is that, as with the income tax, there has been little to no thought put into whether or not the tax conforms to sound, basic principles of taxation. And unfortunately this problem continues to this day. In 2009, the General Assembly formed a Joint Finance Committee on Tax Reform (JFCTR). The directive from the legislature simply stated:

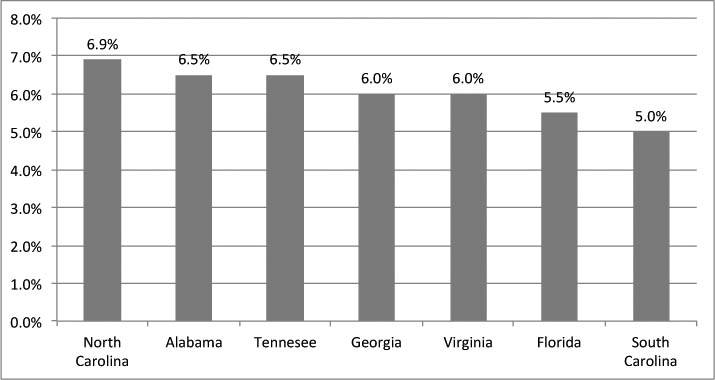

While using the term "reform," this language simply directed the JFCTR to come up with recommendations for a particular set of changes. It gave no indication that the changes should be rooted in what anyone who has rigorously thought about tax reform would recommend. The directive does not address whether such changes would be sensible in terms of making the tax system more efficient from an economic perspective or more just from an ethical perspective. In other words, it gives no reason for making those changes. The issue that policymakers and the JFCTR have focused on the most is the fact that North Carolina's sales tax is imposed only on goods and does not, at least directly, include services. And certainly that is what was meant to be the focus by the JFCTR when it was directed to come up with recommendations for broadening the base. By services I not only refer to haircuts, lawn care, house painters, etc., but also professional services such as legal, accounting, and medical. As an aside, we will see below how most of these services are taxed, to some degree, indirectly. The reason why the focus has been on expanding the tax to services is that it tends to be seen as having significant revenue-raising potential. It is not often presented as part of an overall strategy of making the sales tax conform to the sound principles of taxation discussed above. For example, in testimony before the JFCTR, Michael Mazerov from the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Budget and Policy Priorities stated, "there is enormous revenue-raising potential in the sales taxation of services." In fact, Mazerov estimates that North Carolina could raise an additional $1.5 billion a year by extending the current sales tax to services purchased by households.6 But from the perspective here, tax reform should not be about increasing tax revenues but about fixing the tax system so as to conform to sensible, economic growth-enhancing principles of tax policy. In this respect, extending the tax to services should be one part of a reform package, but reform that did only this would not be an improvement. In fact, the sales tax includes one important element in its base that actually makes it too broad, the sales of goods from one business to another. That is, it taxes goods that are sold as inputs to other production processes. The problem with taxing business-to-business sales is that all of these taxes are ultimately paid by the consumers of these goods in the form of higher prices. This means that these taxes are hidden from the consumers who are actually paying them, fooling consumers into believing that the total sales tax they are paying is less than it actually is. In the process, the system hides the true cost of state government from voters. Furthermore, since consumers are paying explicit sales taxes on the full prices of the products they buy, which includes business-to-business sales taxes on products that were inputs into their production, they are paying a tax on a tax. The system is, to some extent, taxing the same purchase twice. It is because of the business-to-business tax that we cannot say that consumer services are completely untouched by North Carolina's sales tax. For example, the haircutting services of a barber are not directly taxed, but the clippers, combs, shampoo, barber chairs, and cash registers are when purchased by the business owner. As noted, the customer bears the cost of these taxes in the form of higher prices. This is why I noted above that services are, to some degree, taxed indirectly. Any reform of the sales tax would have to include not only extending the tax to services but also abolishing all taxes on business-to-business sales. To proceed with the former without the latter, would extend double-taxation, which is probably the most egregious problem with North Carolina's tax system as it violates both basic principles — neutrality and transparency. North Carolina's Corporate Income TaxIn addition to the problems discussed above with the personal income tax, North Carolina further punishes investors with a separate tax on corporate income. First, it should be pointed out that the corporate income tax does not tax corporations. A corporation is a legal and accounting entity and as such cannot pay taxes. All taxes "paid" by a corporation must ultimately come out of someone's pocket. These individuals come from one of three groups — corporate stockholders, who pay in the form of lower dividends or capital gains; the corporation's employees, who pay in the form of lower wages or fewer jobs; or customers, who pay in the form of higher prices. A mix of these three groups will always pay corporate taxes. So they add a third layer of taxation on stock dividends and capital gains from the sale of stocks. They also add additional layers of taxation on workers and reduce the purchasing power of shoppers. Corporate taxes are hidden from those who actually pay them and are a particularly dishonest form of taxation. The hidden nature of corporate taxation also makes the taxes easy to demagogue by those who want to raise taxes while making people think that someone else — such as a "greedy" corporation — is paying. Furthermore, North Carolina's corporate income tax, at a rate of 6.9 percent, is not only the highest in the region but also the 21st highest in the nation. In addition to these problems, politicians use it as a negative slush fund. Statutorily the rate is 6.9 percent, unless you are a politically favored business and have a niche carved out for you in the law. It is riddled with special breaks and exemptions for those who carry out their business the way the government wants them to.

Because of all of these problems, our belief is that the there is no point in reforming the corporate income tax and that it should be repealed as part of any overall tax reform, which will be discussed below. And the RestNorth Carolina has several other taxes, some worse than others. Together they make up 8 percent of the state's general fund revenues. These include estate taxes, franchise taxes, special excise taxes on tobacco and alcohol, and a few others. Strictly speaking none of these conform to the principles of neutrality or good government outlined above, and I will not discuss all of them here. But clearly there is one that should be singled out in terms of penalizing investment and economic growth — the estate tax. North Carolina's estate tax, sometimes referred to as the death tax, kicks in after $3.5 million of inheritance. This mimics the federal estate tax. Above this threshold the tax is steeply progressive maxing out at 16 percent, which applies to estates above $10 million. Estate taxes are a second, and in many cases a third, layer of taxation on the same income. Typically income is from accumulated investments and the returns on those investments, often in building a business or farm, or in property that is used to generate income. Much of this income was taxed first before it was ever invested. On top of that, the returns on the investments were taxed (see the previous discussion of the income tax) and, with the estate tax, it is taxed again when it is left to one's children or other heirs. These accumulated tax penalties discourage entrepreneurship and economic growth. The franchise tax, levied on capital stock or property, is levied on company owners "for the privilege of doing business in North Carolina," as the Department of Revenue website puts it.7 Everything that was said about the corporate income tax applies to the franchise tax. It is an additional layer of taxation on investment, which, if you're counting, could be as many as four, and is completely hidden from those who actually pay it. Finally, I want to mention excise taxes. These are basically sin taxes on sales of tobacco and alcohol. These are additions to the sales tax meant to disproportionately and negatively influence the freely made choices of North Carolina citizens. Not only are they an example of poorly conceived and inefficient tax policy, but they are inconsistent with the role of government in a free society. What Direction for Reform?If North Carolina could start from scratch, what would be the best possible tax system in terms of raising the revenues needed for government operations while meeting the objectives of economic neutrality and good government? In other words, how can we construct a tax system that does not disproportionately discourage work effort, saving, and economic prosperity and also makes clearer to citizens how much they are paying? A simple, single-rate tax levied only on income used for final consumption will come closest to meeting these criteria. Above we showed how the current income tax is harming North Carolina's economy by double-taxing saving and investment, thereby discouraging entrepreneurship. With some adjustments, North Carolina's income tax base can be reformed such that it only includes income used for consumption purposes. In other words, it can be converted from an income tax to a consumption tax, while legally keeping the structure of our current tax system. Since, with the exception of charitable giving, all income is either spent on consumption goods and services or saved and invested, we can convert the income tax into a consumption tax by subtracting net savings from the tax base. This new tax system would treat all savings and investment in the same way that IRAs and 401(k) retirement investment plans are currently treated, except that there would be no penalties for withdrawing funds before any legally specified length of time. The interesting feature of such a tax is that, in fact, it doesn't mean, as one might think, that the returns to saving go untaxed. Instead both consumption and saving are taxed equally. This can be demonstrated by making reference to the example under the "Penalizing saving, investment, and entrepreneurship" section above. What if we took out of the tax base all income used for saving, with the tax and interest rates remaining at 10 percent? If the person in the example decided to spend his $100 in pre-tax income, he would be subject to the 10 percent tax immediately and would have $90 available for consumption purposes. But if instead he decided to save the $100 for a year, he would not be taxed on it until it was taken out of savings and used for consumption. At the end of a year, if he chose to withdraw the money from savings or to cash in his investment, the original $100 and the return of $10 would be taxed at a rate of 10 percent. This would leave him with $99 for consumption purposes, or the equivalent of a full 10 percent return on $90. If you recall from the previous example, the returns to saving/investment were reduced once when the income was first taxed and before it was directed toward saving, and then those returns were taxed or reduced a second time when the interest was taxed. By taking saved income out of the tax base, both the principal and the interest are taxed, but only once when they are ultimately spent. Public-finance economists call this a "consumed income tax." It is also referred to as the Unlimited Savings Allowance, or USA, tax, which is how it will be referred to for the remainder of this chapter. Functionally, this would be the equivalent of a perfectly constructed sales tax, i.e., a sales tax that eliminates all of the problems that are discussed above. Like the sales tax, the USA tax would also only tax income that is used for consumption purposes. The key difference is not analytical but practical. The responsibility for collecting and ultimately paying the sales tax is not with the earner of the income, the individual consumer, but with all of the separate businesses with which the consumer is doing business. And instead of it being paid all at once, it is collected piecemeal, at each individual point of sale. The sales tax unnecessarily adds a middleman to the process with all of the associated extra burdens. This year the North Carolina General Assembly has an opportunity to take positive action and pass meaningful comprehensive and principled tax reform. Based on the analysis and ideals discussed above, the John Locke Foundation is offering two possible proposals. The centerpiece of both of these reforms is the transformation of the current state income tax — which we believe is the tax that is doing the most damage to our economic system — into the consumed income or USA tax as outlined above. We are not indifferent between these proposals and discuss them as being our "first-best" and "second-best" alternatives. On the other hand, we believe that either proposal would be a vast improvement on North Carolina's existing tax code. Furthermore, empirical analysis provided by the Beacon Hill Institute at Suffolk University in Boston demonstrates that either proposal would have a positive impact on the state's economy.8 Our "first-best" proposalIdeally North Carolina would replace all of its current tax revenue with a single rate USA tax. This would eliminate the biases against saving and investment and reduce the bias against work effort found in the existing income tax. But realistically that is not likely to happen. The most important reason for this is that the North Carolina state constitution specifies that income tax rates cannot go above 10 percent.9 For legal purposes, the USA tax would still be considered an income tax, not a consumption tax, even though in reality and for purposes of economic analysis it is clearly the latter. This means that, on a revenue-neutral basis, it would be legally impossible for all tax revenues to be replaced by just this tax since to do so would likely require a rate above the constitutional limit. This is why our "first-best" proposal would not replace all of the taxes collected by North Carolina's state government. Our focus is on eliminating those taxes that especially penalize saving, investment, and economic growth. Given this, our "first-best" recommendation is to abolish the personal income tax, the sales tax, the corporate income tax, and the estate tax, replacing them all with a single rate USA tax. This would eliminate the most significant biases against productivity in the income tax plus the uneven taxation of purchases as represented in the current sales tax. A few other specifics should be noted about this plan. First, in addition to direct savings and investment, we propose a tax exclusion for educational savings and expenditures. The logic is that at least some share of education spending acts as an investment in what is called "human capital." It is not current consumption, like buying a stereo or going to a Broadway show. Spending on education is expected to yield a future return, much of which will be monetary. For this reason, we provide for education savings accounts (ESAs) in which people would not only be allowed to make pre-tax contributions — as would be the case with other saving accounts — but also not be taxed on withdrawals as long as the money were spent on tuition, tutoring, or other education expenses. North Carolina already has a similar arrangement for college tuition with its 529 college savings plan. In addition to allowing parents to deduct educational savings and spending, our plan also allows individuals to take 40 percent of their current federal personal exemptions and includes full deductibility for charitable giving. This proposal also would institute three major changes with respect to the tax treatment of home ownership sales. Households could use their USAs to accumulate pre-tax funds for making a downpayment. Interest, dividends, and capital gains would build up in savings accounts without extra layers of taxation. Then, after making a taxable withdrawal to use as a downpayment, households would never pay income tax on any capital gains from the subsequent sales of the home. This would apply to all home sales, not just primary residences, with no cap on the amount of gains that are realized. This would eliminate any double taxation on that portion of a home that acts as an investment for the home owner. What will be paid for out of after-tax income will be mortgage interest, insurance, maintenance, and other operating costs of the home. This would treat the purchase of a home like what under current tax law is called a Roth IRA. Under a Roth IRA, after-tax income is used for savings or other investment purposes while the returns on the investment are exempt from taxation. With the tax reform being proposed here, a home would be purchased with after-tax income while any investment return, the capital gains on the sale, would be tax-exempt. What do the numbers say?As noted, an analysis of the John Locke Foundation's consumed-income tax proposal has been conducted by a team of economists at Suffolk University's Beacon Hill Institute (see their report here). They have calculated the USA tax rate that would be necessary to replace all tax revenues currently collected via the income tax, sales tax, corporate tax, and estate tax, leaving all others in place. This is what is known as a "revenue-neutral" tax rate.10 Their study concludes that the flat rate would need to be about 9 percent (remember, the state's retail sales-tax rate in this scenario would be zero). This is a "static calculation," which means that it is not extrapolating from any expansionary effects on economic growth that the tax reform might have. The Beacon Hill Institute has also calculated a second, dynamic revenue-neutral rate given this same tax base. The dynamic rate takes into consideration the economic growth effects that would be associated with the tax reform, which are significant. Consistent with the economic theory discussed above, Beacon Hill concludes that there will be very significant positive economic growth effects from adopting a consumed-income tax, which will in turn expand the tax base. In fact, they estimate that taking this approach to tax reform would increase North Carolina's GDP by more than $11.76 billion in the first year and by almost $13 billion after four years with an immediate first year increase in employment of 80,500 jobs and an employment increase of 89,000 jobs by 2017. If these impacts are taken into account then the revenue-neutral USA tax rate falls to 8.5 percent. We recommend that the legislature, in considering this proposal, target the dynamic rate. To assume no growth effect of making such a transition would be unreasonably conservative and inconsistent with good economic analysis. If the legislature were to entertain a proposal closer to the 9 percent static rate then it should be written into the law that any surpluses that are generated due to the dynamic effects of tax reform should be earmarked for USA tax rate reductions. Why Not Reform the Sales Tax?One might question why we suggest reforming the current income tax by transforming it into a consumption tax rather than abolishing it completely and reforming the sales tax, as some are suggesting. While conceptually the sales tax could be reformed to conform to the principles outlined above, there are several problems that arise due to the fact that the tax is collected at point of sale. The USA tax automatically taxes all consumption equally by taxing it as a category. Consumption spending is reduced by the tax rate. This would also be the case with an "ideal" sales tax, but reaching or coming close to that ideal is much more difficult with the sales tax than it is with the USA tax. With the USA tax, the nature of individual consumer purchases are irrelevant and are less likely to come into play as part of the political process. Because the sales tax is collected at each point of sale, it becomes more susceptible to political manipulation. It is much easier to exempt some goods or services or to differentiate rates for one industry or another based on that industry's political clout or on public sentiment. In transforming the current sales tax into an efficient and transparent consumption tax, especially in extending the tax to services, each individual industry will become a special interest group arguing that the tax should not apply to it or that it should face a reduced rate. And when one considers that many of these groups already have considerable political clout — for example, lawyers, doctors, hospitals, and bankers — the probability of having to fight a host of individual political battles seems quite high. Also, because individual venders do not collect the USA tax, administrative and logistical problems like those that are encountered when dealing with Internet purchases disappear. Purchases at brick-and-mortar retailers would automatically be treated the same as online purchases, without any action needed by Washington. A "Second-Best" ProposalIf full-bore adoption of a USA tax proves impossible, the next-best solution would be to replace the revenue from the personal and corporate income tax and the estate tax with a USA tax while leaving the existing sales tax in place. This would remove what are clearly the three most economically damaging taxes from the current system. While the sales tax has certain problems, as discussed above, it is fundamentally a consumption-based tax and does not have the punitive effects on investment that the other taxes have. We also believe that it would not be politically practical to attempt to make the necessary changes to reform the sales tax properly while at the same time transforming the income tax into the USA consumption tax, again for reasons discussed above. The Beacon Hill Institute also has estimated both static and dynamic revenue neutral rates for the USA tax for this proposal given that the revenue from the current sales tax remains as part of the base. They estimate that the static USA tax rate would fall to 5.78 percent, from the 9 percent required under our "first-best" proposal. Under this "second-best" scenario, the state sales tax rate would continue at its current rate of 4.75 percent. In examining the dynamic impacts, we asked the Beacon Hill team to estimate the growth effects of a revenue-neutral tax reform package that would maintain a 6 percent USA tax rate and, instead of keeping the state sales tax rate as is, reduce it to 4.5 percent. While this too would have positive growth effects for the state, they would not be as significant as the effect found with our "first-best" proposal. Real GDP for the state is predicted to rise by about $4 billion in 2013 and by about $5.8 billion by 2017. The economic growth will produce about 10,000 jobs in 2013 and nearly 14,000 by 2017. If the political will is not there to move forward with our "first-best" proposal, then we believe that this approach, with a 6 percent USA tax rate and a 4.5 percent sales tax rate, would be a reasonable alternative. We would also like to point out that all of these estimates assume no change in revenue to the state and therefore no reductions in spending. We clearly do not believe that government spending in North Carolina is optimal. Indeed, we have consistently advocated lower levels of spending. With spending cuts could come lower rates which would, in turn, further boost economic growth and, depending on the size of the cuts, increase job creation by many thousands in both of the scenarios here outlined. Administering a North Carolina USA TaxUnder these reforms, regardless of whether the sales tax is jettisoned or kept, the process of filling out state tax returns would not change a great deal. Anyone required to pay income tax in North Carolina would start with the relevant share of adjusted gross income (AGI) from his federal tax return (which currently accounts for deposits into tax-sheltered accounts.) From AGI, tax filers would first take their personal exemptions, which in our plan would be calculated by multiplying their federal personal exemptions by .4 (40 percent). They would then deduct charitable contributions. Finally, they would deduct all other net savings — additional income placed in savings accounts and other investment vehicles, including stocks, bonds and mutual funds, and any interest and dividends that are rolled over minus the amount taken out of any of these accounts and not reinvested (unless the withdrawals were used for educational expenses, as previously discussed). If the federal government had a more sensible income tax system — a flat tax with an unlimited allowance for net savings — then adopting such a system in North Carolina would be simple. Instead of the current set of IRAs, 401(ks), 529 plans, ESAs, and HSAs, with their wide variety of limitations and specifications, the federal system would allow all households to put unlimited amounts into these savings vehicles using pre-tax dollars. Because the accounts are already subject to annual reporting to the Treasury Department on the net inflow-outflow of funds (such as Forms 5498 and 1099-4), it would be easy for households and the government to compute the appropriate amount of tax deduction for net savings. For example, if you put $7,000 into your IRA for retirement and $2,000 into an ESA for your daughter's future college expenses, and took out $3,000 from your USA to use as a downpayment on a car, your net savings that year would be $6,000. North Carolina could piggy-back on the system, using the inflow-outflow reporting to compute the net-savings deduction for state income tax. Obviously, that is not the current situation. While North Carolinians can and do exclude the pre-tax savings currently allowed under federal law for IRAs, ESAs, and other savings vehicles, a properly structured consumed-income tax wouldn't put caps on annual deposits or exclude some households from participation based on income, as current federal law requires. So in order to adopt a true consumed-income tax in North Carolina, we will have to supplement current federal tax reporting with something else. One option would be simply to allow all those filing income tax in North Carolina to compute and report their net savings every tax year, relying on the honor system and the risk of audit to ensure that taxpayers do not abuse the system — by faking or double-counting the amount saved, for instance. While North Carolina currently enforces other state tax provisions this way, many policymakers would be understandably wary of such an approach given the significant sums and revenue implications involved. Fortunately, there is another option. North Carolina can authorize a new savings vehicle available to all taxpayers who file income tax in the state. It would function just like the current federal IRA, except that deposits would be unlimited and withdrawals prior to retirement would be subject to tax only, not penalties. Banks, mutual-fund companies, and other financial firms would be allowed to offer these accounts — let's call them Carolina USAs — to anyone whose earnings subject them to income tax liability in the state. They would be required to send annual inflow-outflow statements to depositors as well as the state Department of Revenue. Would these Carolina USAs have some compliance costs associated with them? Certainly, but not significantly different from the kinds of reporting requirements already associated with IRAs and the like. Moreover, the administrative costs would obviously be far lower, and more limited in scope, than those associated with broadening the scope of the retail sales tax to include entire service industries that previously had no responsibility to collect and remit state sales taxes. The Carolina USA solution is logical and practical. Still, if there are any unforeseen and fatal flaws with the proposal, there remains one final option. Rather than treating all net savings in North Carolina as if it occured within a traditional IRA — in which you get deductions going in and pay tax on what comes out — we could treat net savings like a Roth IRA. That is, we could tax the principal of all investment going in and then exempt the return on that investment. In other words, we could change North Carolina tax law to treat interest, dividends, and capital gains as non-taxable forms of income. There are actually good reasons to prefer the Carolina USA model, both practical and political, but the point is that policymakers should not allow enforcement issues to prevent the adoption of a sensible tax policy for North Carolina. ConclusionNorth Carolina's tax structure penalizes economic growth and is a factor inhibiting our state's success in the 21st century economy. Saving, investment, and entrepreneurship, which are the engines of capital formation and economic growth, are double-taxed — and sometimes, because of the corporate income and estate taxes, they are triple-taxed. The principles and economic analysis discussed here are a well-established part of the ongoing national discussion of the economics of taxation. And, in fact, over the years, the federal income tax code has moved, albeit slowly and in a piecemeal fashion, in the direction of applying these principles. Traditional IRAs, Roth IRAs, and 401k and 403b plans are all examples of this. So are Health Savings Accounts and college-savings plans. At lower levels of government, some states have historically pursued a different course, levying a sales tax but no income tax, at least on wage income. In our region, both Tennessee and Florida have this model. It should be pointed out, however, that both of these states continue to penalize investment activity. They both have a corporate income tax. In addition, while Tennessee does not have an income tax on regular income, it does tax investment income from stocks and bonds. Furthermore, the sales tax in both states violates the neutrality principle by not including services in the tax base. On the other hand, both Florida and Tennessee should be commended for not including business-to-business sales in their sales tax bases. As discussed, the principles behind the "sales tax only" approach to reform are the same as those endorsed in this chapter, tax neutrality and transparency. But, as discussed above, we believe that for North Carolina the political practicalities of moving in this direction, given our current system, would be insurmountable and end up producing a special-interest frenzy with very little accomplished in terms of real tax reform. It is our belief, backed up by economic theory and quantitative analysis, that the proposals made here to transform North Carolina's income tax into a consumption-based USA tax, while abolishing the state's corporate and estate taxes, has the potential to generate strong incentives for businesses in the state to expand while attracting and stimulating new investment, economic growth, and job creation. The elimination of the corporate income tax would make North Carolina one of only four states with neither a corporate income tax nor a gross receipts tax and the only state in the eastern half of the US with neither tax. This would make the state very competitive, acting as a magnet for economic expansion. The politics of making such significant changes will not be easy to navigate. There will be special interests that benefit from the current tax code and will resist change. But for the general welfare of North Carolinians, state policymakers should resist these pressures and be willing to make some difficult but constructive choices. Endnotes1 Historical information provided by the N.C. Division of Revenue. 2 For a more extensive narrative of this history see presentation titled "History of State and Local Taxes in North Carolina" by Roby B. Sawyers, Ph.D., CPA, NC State University. http://bit.ly/UhBLHs. 3 Robert Murray Haig and Carl Shoup, The Sales Tax in America, New York: Columbia University Press, 1934, pp. 186-193. Neil Jacoby, Retail Sales Taxation, New York: Commerce Clearing House, 1938. 5 Study of North Carolina's Sales and Income Tax Structure, Interim Joint House and Senate Finance Committees. 6 Michael Mazerov, "Sales Taxation of Services: Options and Issues," presentation to the Interim Joint House and Senate Finance Committees, North Carolina General Assembly, December 1, 2009, http://www.ncleg.net/gascripts/DocumentSites/searchDocSite.asp?nI=56&searchCriteria=mazerov. 7 NC Department of Revenue, Franchise Tax Information, "Who Should File," No.9, "Franchise Tax Payable in Advance," http://www.dor.state.nc.us/taxes/franchise. 8 David Tuerck, Paul Bachman, and Michael Head, "A Consumed-Income Tax Proposal for North Carolina," http://s3.amazonaws.com/site-docs/research/BH-tax-study.htmlBeacon Hill Institute, Suffolk University, December 2012. 9 North Carolina State Constitution, Article V, Section 2, Subsection 6. www.ncleg.net/Legislation/constitution/ncconstitution.pdf. 10 As noted this assumption of revenue neutrality should not be taken as an endorsement of current levels of state spending. Indeed we believe that the state budget should be significantly cut. Our proposals for budget cutting can be found in the most recent John Locke Foundation alternative budget. See Joseph Coletti, "Protecting Families and Businesses: A Plan for Fiscal Balance and Economic Growth," John Locke Foundation, Spotlight No.408, February 2011, http://www.johnlocke.org/research/show/spotlights/259. |