Public Transit

Recommendations

The following are ways community leaders can meet transportation needs effectively within limited transportation budgets:

Provide mobility. Transportation is about providing mobility, not about reshaping the community or defining away the automobile, consumers' mode of choice. Planners should build to serve people's needs, not try to make them "need" something else.

Privatize when possible. Local rules preventing jitneys, private vanpools, and other for-profit paratransport options are outdated — they were first established in the early 20th century to protect electric rail cars from competition from upstart automobile owners — and have been obsoleted by their successful use in several foreign cities.

|

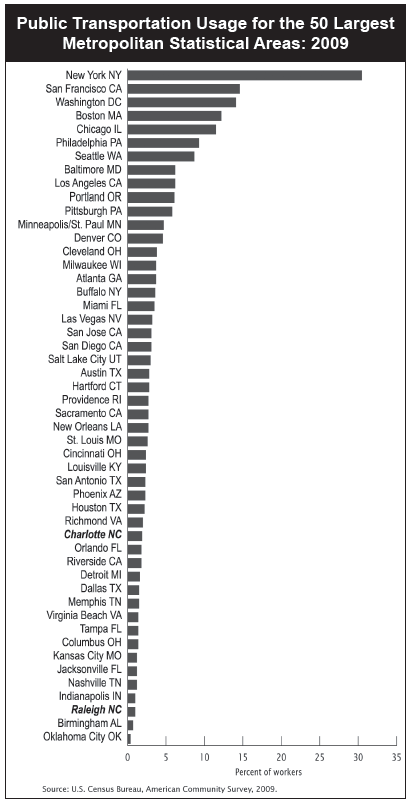

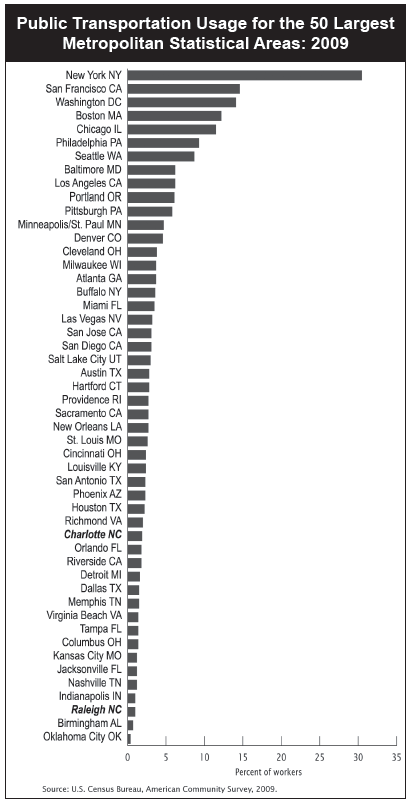

Spend on transit options proportionate to their demand. Spending should be commensurate with how much individuals actually use transit. Only in the densest metropolitan areas does public transit (including bus, rail, subway, ferry, etc.) attract more than 5 percent of commuters (see Chart 2). Over time, diverting resources disproportionately to low-demand transit options leaves highways and roads unable to handle their high demands sufficiently.

Treat congestion at the source. The solution to a troubled intersection is not to expand public transit options and hope that they will divert drivers. Apart from adding more road capacity, planners could derive smoother flow through, among other things, traffic signal optimization, more responsive traffic incident management, and increased left-turn capacity. In 2012, the City of Raleigh announced an overhaul of its traffic signal timing and expanded monitoring of intersections (including the ability to access signals near accident sites) to improve traffic flow.

Avoid the "romance of rail." For reasons discussed here, rail is a poor way of meeting transit needs. Practical transit improvements, such as better bus systems and optimized traffic signals, may not be as "world class" or exciting as rail transit, but they are more cost-effective and flexible and move people more efficiently than rail.

Background

Public transit is ultimately about people. A public transit system should meet the actual transportation needs of the citizens. Its aim should be to provide mobility for citizens in the most efficient, effective ways possible.

The concept is as simple and sensible as it is controversial. Planners too frequently attempt to use transportation policy to shape their communities to conform to their visions, rather than fit their transportation policy to meet travelers' needs.

The consequences of poor transportation policy aren't limited to creating frustrated commuters. Research finds traffic congestion harms an area's economic growth. Traffic jams and even the expectation of congestion negatively affect productivity, employment, company profits, and consumer prices.

Analysis

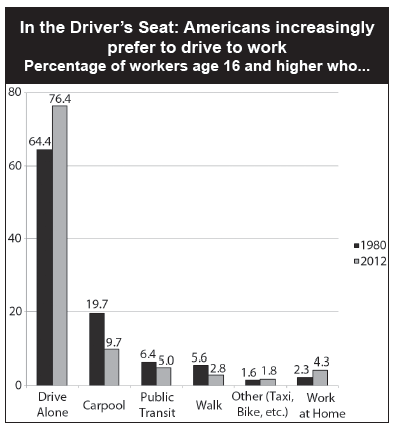

The most obvious fact of transportation in America in the 21st century is that people overwhelmingly prefer personal automobiles (see chart). Cars offer the greatest range of mobility and fastest arrival at destinations, along with privacy, choice, adaptability to wants and needs, and individuality. This freedom is reflected in a well-known expression for being in control of a situation: to be in the driver's seat. That is what people prefer, and that choice is what good transportation policy recognizes.

Next to that is busing, since buses can also offer a wide range of routes and possible routes, which may be adjusted to fit changing passenger needs. Another advantage of buses is that they make use of preexisting transportation capital (roads).

On the other end, fixed-rail lines offer no flexibility in terms of route, and they require enormous capital expenditures to set up as well as operate. They also attract very few riders — fewer than one percent of the share of motorized passenger travel in all but the largest, densest metropolitan areas.

Nevertheless, rail transit appeals to planners' desires to shape their communities in very specific, rigid ways. Using scarce transportation dollars on achieving their vision rather than citizens' needs is a sure way to increase congestion and hinder economic growth.

As shown in David T. Hartgen's 2007 report "Traffic Congestion in North Carolina," several N.C. cities were heavily and disproportionately invested in public transit, led by Charlotte (57.5 percent share of funds vs. 2.6 percent share of commuting for transit), Durham (50.7 percent vs. 3.0 percent), Raleigh (27.5 percent vs. 1.2 percent), Greensboro (19.5 percent vs. 1.3 percent), and Wilmington (13.0 percent vs. 0.9 percent).

Analyst: Jon Sanders

Director of Regulatory Studies

919-828-3876 • jsanders@johnlocke.org

The entire 2014 City & County Issue Guide, is available for download as a 3.6MB Adobe Acrobat file.

The free Adobe Acrobat Reader is required to view or print this document.

|